Rising Brazil: The Choices Of A New Global Power

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

A Brazilian federal judge on Sept. 24 stripped the patent protection of Gilead Sciences’ hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir, sold under the brand name Sovaldi, at the behest of then-presidential candidate Marina Silva, who argued that the move would reduce costs that patients must pay. Will the judge’s move benefit public health by making the drug more available, or will it dissuade drug companies from producing needed pharmaceuticals? How big of a problem is hepatitis C in Latin America and the Caribbean, and which countries have done most to contain it? What kinds of efforts should countries and the private sector make to fight hepatitis C?

Ryan McKeel, director of public affairs at Gilead: “Approximately 2 percent of adults in Latin America—at least 10 million people—are chronically infected with hepatitis C, which can lead to serious and life-threatening liver damage, including cirrhosis, liver cancer and the need for liver transplantation. Gilead is proud of our efforts to bring curative therapies to people living with hepatitis C in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2016, we entered an agreement with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to provide our hepatitis C medicines at heavily discounted prices, including our lowest-tier prices, for use in countries throughout the region. We continue to work with governments, physicians and patient organizations in the region to support hepatitis C education and screening. In Brazil, we are committed to supporting the national government’s hepatitis C elimination project and extending access to our medicines to all patients in need. We have confidence in the technical assessment conducted by the Brazilian authorities responsible for patent granting and registration. It is the duty of these authorities to assess patent applications from a strictly technical point of view, thus promoting innovative research and development on a national and international level. Since the patent case is an ongoing legal issue, we cannot comment further on it. Importantly, we remain committed to supporting the Brazilian government in the eradication project and extending access to our drugs to all patients who are in need of them.”

Núria Homedes, associate professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Texas: “It is estimated that 7.2 million residents in the Americas carry the hepatitis C virus (4.1 million reside in Latin America and the Caribbean) but only 25 percent know it and about 4 percent are receiving treatment. If untreated, about a third of the infected will develop severe liver disease. Today, science has the means to successfully treat 90-95 percent of those infected with hepatitis C but Gilead, the producer of sofosbuvir, is selling it at extraordinary prices that are beyond the reach of most patients and public health systems. Gilead argues that the treatment is cost-effective because treated patients will no longer need a liver transplant. However, sofosbuvir’s production costs has been estimated at $68-134 per treatment. Selling it at cost with a reasonable profit would save millions of lives, halt the spread of a serious disease and may even contribute to limiting antibiotic resistance. The benefits for humankind could be extraordinary and should far outweigh the benefits to Gilead and its investors. Public health experts and human rights advocates are rejoicing with the decision taken by the courts in Brazil. Mindful that inaccessible medicines do not produce health gains, U.N. agencies, other global governance institutions and several countries have publicly committed to facilitating access to treatments and combating antimicrobial resistance. Other countries such as China, India, Egypt, Ukraine, Argentina, Thailand and Russia have challenged the patents and/or have issued compulsory licenses to benefit their populations. If the industry is unwilling to collaborate, these entities and governments will have to use all legal loopholes and new initiatives to facilitate access to life-saving medicines in a sustainable manner. Patents should not trump human lives.”

Carl Meacham, member of the Advisor board and associate vice president for Latin America in the international advocacy division at Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA): “Measures that undermine intellectual property rights will not bring long-term, reliable benefits to Brazil’s health care system or its patients. Such approaches have failed in securing more accessible medicines in other countries and have begun to damage valuable bilateral trade relations with the United States. Unilateral actions against intellectual property protections, such as the one taken by the Brazilian court, also endanger capital investment and knowledge sharing. After Colombia began to pursue actions to strip temporary patent protections during the past administration, clinical trials in the country decreased by 60 percent. Certainly, Latin American countries and the private sector should continue to strengthen collaboration efforts to ensure that all patients have access to medicines that can cure hepatitis C. But efforts must take a different direction than the one suggested by former candidate Marina Silva. It is not by stripping protections to medicines that patients gain access to life-saving medicines. Rather, Brazil should be promoting policies that focus on patients and improve market efficiency and competition. In particular, Brazil should work to eliminate regulatory delays and roadblocks, promote competition and access to a wide variety of innovative medicines, find sustainable solutions through public-private partnerships and eliminate trade barriers on medicines. It is only through innovation and collaboration that health care outcomes can improve for all Brazilians.”

Katherine Bliss, principal at Girasol Global Policy Consulting and senior associate at the CSIS Global Health Policy Center: “In Latin America and the Caribbean, viral hepatitis, including that caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), accounts for 10 percent of all deaths. HCV is transmitted through contaminated medical equipment and blood transfusions, as well as injection drug use. While there is a regional plan of action to prevent and control viral hepatitis, and all countries in the Americas have the capacity to do serological testing for HCV, only 54 percent report using the rapid HCV test approved in 2016, and the burden of HCV infection at the national level is poorly understood. Some countries provide free HCV testing for people who inject drugs, people living with HIV/AIDS and pregnant women, but the cost for other people at risk of infection can be prohibitive. Direct-acting antiviral medicines to cure HCV became available in 2013, but the price for the patent-protected drugs has remained high. In Brazil in 2016, a 28-day dose of Gilead’s Sovaldi was $2,292, while in Argentina, where the price for the patented drug was slightly less, a generic version was available for $501. Allowing domestic pharmaceutical manufacturers to produce the drug at lower costs will enable national health programs to better fund treatment for all who need it. Treating more HCV-infected patients will encourage more people to get tested, leading to a clearer understanding of HCV prevalence in the region. Encouraging public-private collaboration to improve the safety of blood transfusions, reduce unnecessary injections, introduce single-use injection devices and provide harm-reduction programs for people who inject drugs will also be important.”

Andrew Rudman, managing director at Monarch Global Strategies: “Patients, public health officials and biopharmaceutical manufacturers alike share the goal of improving access to life-saving/life-improving medicines. Unfortunately, the Brazilian court’s decision underscores, yet again, the lack of understanding of the relationship between innovation and patient access. Private sector innovation, whether in a multinational company’s laboratory to develop a new drug or in a business incubator to create a new digital assistant, occurs with the expectation that the innovator will be fairly compensated for their intellectual property. Absent the ability to realize a return on their investment, innovative biopharmaceutical companies would be unable to raise the capital necessary to discover, develop and test cures for illnesses like hepatitis C in the first place. The court’s decision therefore may delay entry into the Brazilian market of future innovative treatments. Since drugs cannot be introduced simultaneously in all markets (given varying national regulatory approval procedures), those that provide certainty with respect to intellectual property rights are likely to gain access to new innovations first. While the court’s decision might lead to a less expensive hepatitis C treatment in the short run—assuming Brazilian labs can replicate the production process and meet the stringent requirements for safety and efficacy of the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA)—it may be at the expense of delays in access to future treatment for other illnesses. Working with innovators to reach a balance between patient access and the rights of the patent holder, as has occurred in other markets (including in Brazil) would be a far more effective means of achieving shared objectives than reversing decisions on which market entry decisions may have been made.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A with leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. The publication is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

President Lula da Silva triumphantly announced that he and his Turkish counterpart had persuaded Iran to shift a major part of its uranium enrichment program overseas—an objective that had previously eluded the US and other world powers. Washington, however, was not applauding.

An upcoming meeting between Presidents Obama and Rousseff should not be expected to produce dramatic news or unexpected major breakthroughs.

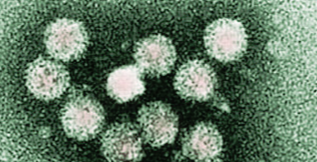

Hepatitis C, viruses of which are pictured above, primarily affects the liver and is spread through blood-to-blood contact. // Image: AJC1 via Creative Commons.

Hepatitis C, viruses of which are pictured above, primarily affects the liver and is spread through blood-to-blood contact. // Image: AJC1 via Creative Commons.