Chinese Reactions to the Brazil Protests

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

In the shadow of millions of Venezuelans fleeing authoritarian rule, Haitians are steadily making a foothold in several Latin American countries. Chile, which has historically received fewer immigrants than its neighboring countries, partly due to its natural Andean “wall,” has recently seen an incredible influx of Haitian migrants. Back in 2002, the national census found that there were 50 Haitians in Chile; by the next census in 2017, there were 64,567 Haitians in Chile, with current numbers looking to be around 150,000. Chile’s migrant population is now 10% Haitian, in close competition with the 12% that is Venezuelan. Why are Haitians choosing Chile in such great numbers, and how has the host country responded?

Haitians have been fleeing their country for decades due to a tragic combination of factors –including a historic dictatorship, widespread corruption, and several devastating natural disasters—that have left almost 60% of society under the poverty line and driven them to seek a better standard of life elsewhere. In fact, 30% of the country’s GDP is from remittances. In the past, Haitians have tended to migrate north to the US and Canada, but recent growth in Latin American economies and restrictive US immigration policies have steered Haitians south. Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Brazil became home to many Haitian migrants, offering them stable employment in preparation for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and a path to residency through a new humanitarian visa. However, once the dust settled and the caxirolas dwindled, Brazil’s economy showed signs that it could no longer offer the same security to these migrants. In early 2016, many Haitians set their sights on Chile, which served as a natural destination given its stable economy and 13-year long military presence in Haiti.

The exponential increase of Haitians in Chile, many of whom are undocumented, has divided the country and unearthed manifestations of racism and xenophobia that are rooted in Chile’s relatively homogeneous demographic history. Reports of anti-Haitian sentiment in Chile are now commonplace, with one of the most striking displays being stickers of Haitian caricatures that resemble the anti-black imagery of the Jim Crow era. Such acts have led Chileans to take part in a long-overdue conversation about race and migration in the country, exemplified by a recent survey on local perceptions of migrants. Some have also taken to the streets to organize national marches and campaigns defending migrants, and the government has taken steps to address integration issues through the new Grupo Tecnico de Inclusion Social. Nonetheless, discrimination is still rampant.

Sebastián Piñera, elected amidst these tensions in March 2018, has kept his campaign promise to reform Chile’s outdated Immigration Act of 1975, but his changes have left many wanting more. Piñera’s new migration policy includes the introduction of visas designed specifically for Venezuelans and Haitians, which allow for a more tailored response to the different realities both groups face but also justify differentiated treatment and a distorted perception of Haitian migrants. Venezuelans fleeing authoritarian rule can now enter Chile on a democratic responsibility visa granting renewable temporary residence, employment, and a path to permanent residence. On the other hand, Haitians are offered a tourism visa lasting 3 months with no possibility for employment, or a reunification visa intended to bring the family members of already-established Haitians to Chile. Those who seek employment must obtain a sponsored work visa prior to their arrival.

While these changes aim to reduce informality among migrants, they do not give enough of an opportunity to Haitians fleeing dire lack of opportunity back home. Due to limited options, the number of visa requests by Haitians fell by 62% by April, but as the situation in Haiti is not improving, particularly with the recent governance crisis, Haitian immigration is unlikely to halt. The failure to provide more avenues for regular migration for Haitians to Chile will likely lead to more illegal immigration, as was apparent with Dominican migrants when similar restrictions were placed on their entry in 2012. Widner Darcelin, a Haitian community figure in Chile, explained that these policy changes have also increased the prevalence of scams against Haitians that promise visa sponsorship and result in labor exploitation. Additionally, the family reunification visa can only be requested in Port-au-Prince, which overlooks the fact that many Haitians are coming from Brazil rather than Haiti itself.

Most importantly, Piñera’s visas categorize Haitians as either tourists or purely economic migrants, which is a misconception of the forces driving Haitian migration. Differentiating between Venezuelan migration as a humanitarian crisis and Haitian migration as a labor-seeking flow is a false distinction. Haitians are coming to Chile to escape a combination of socio-political, environmental, and economic factors, making it difficult to reduce them to economic migrants. The entrenched history of bad governance, corruption, and instability in Haiti might make it easy to normalize massive migration as the status quo, but when only 1 in 10 people have access to clean drinking water and necessary social services are lacking, the line between refugee and economic migrant blurs. If Chile’s migration policy towards Haitians continues to ignore the compounding factors driving their outsized vulnerability to poverty and, consequently, their departure from Haiti, its response will be ill-fitted.

Given that Haitian immigration has increased within the same timeframe as the Venezuelan exodus, coordinating a humane and organized response will be challenging. Chile’s recent agreement with the IOM alleviates the backlog of visa applications in Port-au-Prince but does not address Piñera’s narrow categorization of Haitian migrants. Going forward, Chile should consider extending at least the same humanitarian visa allowances to Haitian’s fleeing their country’s poverty and chaos as it does to Venezuelans. Chile stands to gain much from these new migration flows, which now account for 0.2% of the country’s annual growth, counteract Chile’s aging labor force, and could help diversify the country’s economy. As immigration becomes an undeniable part of Chile’s future, Piñera should keep working to reform the country’s migration policies but should do so with a comprehensive view of the many factors pushing these migrants towards Chile.

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

Unique lens into what those who know education policy best are saying about current trends in Latin America.

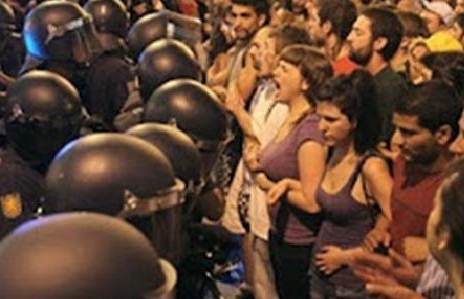

Protests in Chile are a consequence of social successes and failures in the country.