Chinese Reactions to the Brazil Protests

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

This post is also available in: Spanish

In an article on Foreign Affairs, Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela argued that the success of the Chilean transition after the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) was due to the fact that “each group was forced to make concessions, to renounce utopian dreams in order to achieve gradual progress”.

Political stability under the Concertación –the center-left coalition that ruled from 1990 to 2010—and the preservation of the pro-market model installed by Pinochet transformed Chile into one of the most dynamic economies in Latin America. Between 1975 and 2010, GDP grew by almost 5 percent a year, against only 3 percent for Latin America as a whole. Moreover, poverty fell from 45 percent in 1987 to less than 15 percent in 2013, according to the World Bank. In 2015, GDP per capita (adjusted for purchasing power) exceeded $22,000, the highest in the region.

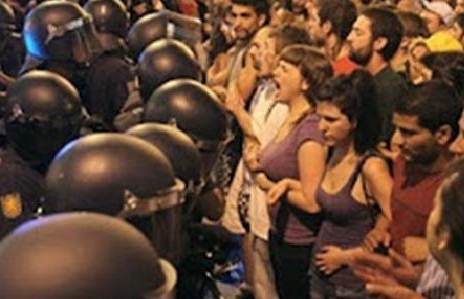

Despite the shortcomings of this “miracle” –such as high income inequality and the deficiencies of the educational system—for more than 20 years Chileans accepted gradualism in order to continue growing and avoid political instability. However, that consensus crumbled during the government of Sebastián Piñera (2010-2014). Many –especially young people—were not willing to maintain the “concessions” and “resignations” of the transition anymore, and took to the streets to demand profound transformations. For new generations, the pragmatism of the political system was no longer a virtue, but a way to preserve an unacceptable status quo.

Facing the risk of losing its connection to youth and poor classes, the Concertación turned to popular former President Michelle Bachelet (2006-2010). Accumulating unprecedented power and autonomy, Bachelet refounded the coalition and incorporated the Communist Party and student movements, launching an ambitious program of structural reforms: free college education, ending for-profit education, raising taxes on corporations, and more bargaining power for labor unions.

Bachelet returned to power with over 60 percent of the vote in the second round, and took office surrounded by immense expectations. Today, however, her popularity is at a historic low (less than 15 percent), and a majority of Chileans reject her reform agenda.

The popularity of the President was based on her personal integrity, as well as her image of being close to citizens. This credibility crumbled in February 2015, when her son was involved in a corruption case, accused of taking advantage of his lineage for private enrichment. Further, this case was only the beginning of a cascade of accusations of illicit deals between the political and business leaders, which affected both the Nueva Mayoria –New Mayority, the name of the Concertación since 2013—and the center-right coalition. For many Chileans, the scandals proved that the success of the transition hid an elitist and exclusivist political and economic model.

Despite these allegations and the collapse of its popularity, the government achieved significant reforms, such as changes to labor laws, a gradual rise in corporate tax from 20 to 27 percent, and reforms to the education system. But with her personal credibility at rock bottom, Bachelet did not have the political capital to regain the trust of citizens. On every reform, the government faced the impossible task of pleasing the more radical sectors of its coalition, such as the students –that want to accelerate the transformations and reject any concession—while confronting the staunch resistance of the business class and the center-right opposition, which accuse Bachelet of excessive interventionism.

The political crisis is exacerbated by an adverse economic environment, with a growth of around 2 percent since 2013. Despite the success of its liberalizing model, Chile’s economy continues to depends on copper (which represents more than half of the country’s exports), just as it has during the 20th century. A drop in international demand –especially from China—led to a fall of more than 50 percent in the price of the metal since 2011. Bachelet’s administration had not prepared for the deceleration, even though it was already evident during the last year of Piñera’s government.

In a context of stagnation, the multiple tax and labor reforms increased business costs and uncertainty, contributing to a sharp drop in investment. This in turn forced the government to break some of its electoral promises: due to the fall in tax revenues, for instance, free university education had to be postponed, stoking tensions with the student movement.

Bachelet’s return in 2014 was an attempt by the parties that had led the transition to regain citizen trust and motivate younger generations. Although it will take time to see the result of the reforms, many Chileans are disappointed. Only 13 percent of those between age 18 and 29 voted in the municipal elections of 2012, against a 43 percent overall participation. 78 percent of the young generation distrusts the political class. Further, the political system seems to be exhausted, incapable of renovation: two former presidents, Piñera for the center-right and Ricardo Lagos (2000-2006) for the center-left, are the most likely presidential candidates for 2018, although with limited support.

The generation of politicians that led the transition has reasons to feel proud of its achievements: against all odds, Chile emerged from a dictatorship, rebuilt its democratic institutions and ensured spectacular economic growth, in large extent due to moderation and consensus. But, because of this success, that Chile no longer exists. The next challenge of the political system is to incorporate new generations –who do not remember the dictatorship or the transition—and those who never felt part of the Chilean miracle.

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

Unique lens into what those who know education policy best are saying about current trends in Latin America.

Protests in Chile are a consequence of social successes and failures in the country.