IACHR Report on Citizen Security & Human Rights

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Colombian President Iván Duque on Sunday night ordered the nation’s military to regain control of the public order in Cali, where there have been lethal clashes among citizens as massive protests continue across the country. The demonstrations began on April 28 after President Iván Duque’s government presented a controversial tax reform plan, but they have morphed into protests of a litany of grievances exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The unrest has sparked international outcry over allegations of police brutality, which the national police force has vowed to investigate. Meanwhile, the government has accused illegal armed groups of infiltrating the protests and causing violence. What is at the heart of the protests in Colombia, and what should the government do to address them? How big a toll will the protests take on Duque’s popularity, and will it prevent him from carrying out his agenda? Will similar protests erupt in other Latin American countries as they seek to emerge from the pandemic?

Francisco Santos, ambassador of Colombia to the United States: “The demonstrations started on April 28 in response to a tax reform proposed to mitigate the country’s economic crisis. Though President Duque withdrew the bill, the protests have continued and have become a broad call for improvements to Colombia’s pension, health and education systems. Consistent with his repeated calls for constructive dialogue, President Duque has implemented a nationwide listening process for citizens and the government to build solutions together. Colombia will continue to protect the fundamental right of its citizens to protest peacefully. At the same time, we will not tolerate criminal acts, vandalism and blockades that have permeated the protests, including those instigated by illegal groups and fringe actors taking advantage of this situation. The government also will not tolerate abuses or excess uses of force by members of the public force and will continue investigating any reports to that end. In terms of President Duque’s popularity, what is important now is finding a peaceful resolution to the situation so that the mass Covid-19 vaccination process can continue, and critical food, medicine and fuel supply chains can be reopened. We are hopeful similar protests will not erupt, and you can be sure Colombia, as a partner in democracy with the United States, will be working to encourage its neighbors to respect fundamental human and civil rights as we all work to reactivate our economies, vaccinate our citizens and deliver progress to our communities.”

Humberto de la Calle, former Colombian vice president, interior minister and chief negotiator in the peace process with the FARC: “Large and unprecedented mobilizations have been present in Colombia since the end of 2019, as a result of citizen dissatisfaction. Although affected by some violent outrages, protests’ message was clear. The government of President Duque opened what I call a ‘national conversation,’ which, however, did not reach any concrete decisions. The pandemic and related lockdowns halted street demonstrations, while at the same time increasing discontent to the point of outrage, given its harmful social consequences. The catalyst for the current protests was a tax reform proposal that, under the pretext of providing fresh resources to the state, included unrealistic tax collection goals. Added to that were previous demands on health, education, universal basic income and no tuition for university studies. All of this came in the context of the government’s eroding popularity and a deep distrust of a political class amid police violence and protesters’ attacks against police forces and citizens’ private property. At the time of this writing, a direct dialogue between the president and the protest organizers is set to begin. Colombians want solutions to be found quickly. The future is worrying, given the need for new resources to provide social relief to the population and the resistance to expanding tax collection. It will be difficult—but not impossible—to find a middle ground. This phenomenon, which occurred already in Chile, could grow even bigger given the hunger and unemployment resulting from the pandemic.”

Arlene B. Tickner, professor at the School of International Political and Urban Studies at University of Rosario: “In all political transitions, including those from authoritarianism to democracy and from war to peace, popular protest customarily increases as pent-up social, political and economic grievances gain room to be aired. However, when ignored or suppressed, the potential for escalation is high. Following the 2016 Havana peace accords between the state and the FARC insurgency, societal demands related to the implementation of the agreement and to deep-seated problems in education, health, work and the environment grew. As in other countries in Latin America, the pandemic has worsened unemployment, food insecurity, poverty and inequality in Colombia, aggravating already existing social discontent. Police forces brutally repressed widespread protests directed initially against President Duque’s highly unpopular tax reform, contributing to a spiraling of violence. The current context of ungovernability and violence, which has reached unfathomable levels in Cali, is compounded by the government’s lack of legitimacy and perceived unwillingness to engage meaningfully with those sectors of Colombian society involved in the protests, including the country’s youth. Duque’s deafness to both Colombian and international calls that human rights be protected, state security forces be held accountable and tensions be de-escalated bodes poorly for peaceful transformation of the protests and genuine national dialogue. Instead, it is more likely that the government will continue to adopt exceptional measures, including the state of internal commotion, to maintain some semblance of authority over an unprecedented crisis that is quickly veering out of control.”

Gwen Burnyeat, junior research fellow in anthropology at Merton College, University of Oxford: “The protests in Colombia express the desperate anger that diverse sectors of society feel toward the Duque administration and the state more broadly. They hark back to the protests of November 2019, after which Duque convened a national conversation that died when Covid-19 hit. Many participants felt deceived by that conversation: it reconfirmed their belief that the state makes promises it never fulfills. Distrust in the state goes back decades, but this conjuncture is rooted in the polarization left by the referendum in 2016, which Duque’s Democratic Center party helped produce by opposing the peace process. Since taking office after rekindling this polarization in the 2018 elections, Duque has not implemented the peace agreement fully, has delegitimized the transitional justice system created to foster national reconciliation and has failed to act on the assassinations of activists and demobilized FARC members, allowing a new cycle of violence to emerge. Colombia needs a new social contract. The best way forward would be to build bridges across this divided society, articulate an agenda that unites the heterogeneity of protesters and define a clear mandate for the next government in 2022, with respect for life, reduction of inequalities and redress for atrocities at the center. Duque’s call for a new dialogue is doomed to repeat history unless he recognizes the legitimacy of the protests and acknowledges his responsibility in the crisis. In the meantime, the priorities must be demilitarization, an end to the abuse of power by armed forces and respect for human rights.”

Elizabeth Dickinson, senior analyst for Colombia at International Crisis Group: “The protesters’ grievances are rooted in Colombia’s profound inequality, which worsened during the pandemic. Yet after nearly two weeks on the streets, the movement’s most salient concerns relate to security forces’ violent response to the protests and the lack of accountability for documented police brutality. The government’s meandering response has made matters worse. President Duque withdrew his tax reform proposal and opened a ‘national dialogue,’ which so far has featured mostly the country’s political and business elite, although Duque met with some young people this weekend and is scheduled to meet with the strike organizers. But the government also persists in treating the protests primarily as a law enforcement concern. Duque has lamented vandalism and insisted that drug traffickers and guerrillas lie behind protest-related violence—a claim that appears to have limited evidence. While in certain areas criminal outfits may be exploiting public rancor—as happened during similar protests in 2019 when FARC dissidents allegedly paid protesters to burn buses outside Bogotá—these groups are not driving the mass mobilization. Moreover, the government’s efforts to link protests to leftist guerrillas in Colombia have in the past paved the way for vigilante violence in the name of restoring order. Incidents in Cali and Pereira, in which civilians have shot firearms at protesters, indicate that this alarming trend could repeat itself. Protesters complain that the security forces, largely unreformed since the 2016 peace accord with the FARC and still under Defense Ministry control, behave as if facing an insurgency rather than young, unarmed activists. Protesters are digging in, especially in Cali and rural areas, where grievances extend to the slow implementation of the peace accord.”

Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, director for the Andes at the Washington Office on Latin America: “While the fuse that lit recent protests was the now-withdrawn tax reform bill, widespread disconnect with the Duque administration had been brewing since 2019. The perception of many of the sectors protesting —labor, students, Indigenous communities, Afrocolombians and others—is that the government is prioritizing the interests of the political and economic elites over that of the majority of Colombians, who have been hit hard by the pandemic. Coupled with that are concerns about police brutality and repression of the right to protest, lack of implementation of the 2016 peace accord and increased insecurity in many parts of the country. While there may be some illegal armed actors and criminals involved in vandalism, the vast majority of the protestors are pacific and within their rights to protest. The state’s response has been brutal and unacceptable—with police allegedly committing at least 37 homicides. The U.S. government must demand a stop to the violence, call for dialogue with the sectors involved in the protests and demand accountability for the abuses committed.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

Since the outbreak of the drug war, Ciudad Juárez has been plagued by unfathomable levels of violence and corruption, leading to thousands of human rights violations.

In June, President Correa issued a decree creating new procedures for NGOs to obtain legal status. What are its implications?

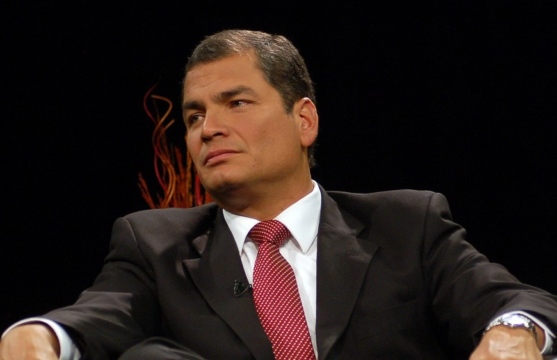

Duque // Photo: Colombian Government.

Duque // Photo: Colombian Government.