Peru’s Election and Beyond: What’s Next?

Peruvians want an evolution, not a revolution.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

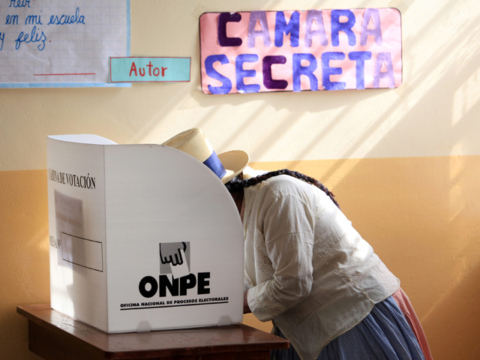

Peru is on edge as a razor-thin margin in Sunday’s presidential runoff election separates socialist Pedro Castillo and conservative Keiko Fujimori. Castillo widened his lead on Monday as vote counting continued, and Fujimori alleged “irregularities” but gave little proof. With 96.8 percent of the votes counted, the ONPE election agency showed Castillo ahead, with 50.3 percent to Fujimori’s 49.7 percent. What do the starkly divided results mean for Peru and for the next president’s ability to govern? How likely is the country to see unrest and claims of fraud by the candidate ultimately deemed the loser? Does the surge in support for a socialist agenda mean that Peru will swing to the left no matter who wins the race?

Cynthia McClintock, professor of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University: “The narrowness of the electoral victory further darkens the prospects for stable, democratic governance in Peru. Extremely narrow electoral victories often lead to challenges and are likely in Peru. After her 2016 loss, Fujimori vengefully mounted unrelenting legislative opposition to the president; Castillo’s political rise was based on his leadership of a prolonged nationwide teachers’ strike. Even before this razor-thin result, prospects were grim. Castillo and Fujimori reached the runoff despite tallying only 19 percent and 13 percent, respectively, in the first round because the field of candidates was immense—18; together, eight relatively centrist, palatable candidates achieved approximately 40 percent. In this context, many legislators will contemplate the impeachment of the president (relatively easy and common in Peru). Fujimori would have a better chance at survival; between her party and the parties that endorsed her for the runoff, she would have 45 percent of the seats. Still, amid an ambitious anti-corruption effort, Fujimori’s history of financial wrongdoing and abuse of power (in particular, intervention in judicial appointments) is common knowledge; her 2021 first-round vote of 13 percent was down from 40 percent in 2016. Fujimori became competitive with Castillo only gradually, as voters’ fears of a far-left agenda mounted (fueled by Fujimori’s campaign ads). In the case of Castillo, between his party and the parties that endorsed him for the runoff, he would have only 32 percent of the seats. Further, although Castillo’s party, Perú Libre, is socialist, Castillo became its candidate only after its platform was written; Castillo has backed away from its far-left positions. To survive, Castillo would probably have to continue to moderate—but this shift could divide his party. Both Castillo and Fujimori (despite her pro-market ideology) made extravagant promises that will be difficult to meet. Sadly, dissatisfaction with this election is likely to spell dissatisfaction with democracy, too, and democracy is in danger.”

Nicolás Saldías, analyst for Latin America and the Caribbean at The Economist Intelligence Unit: “The too-close-to-call race is a testament to Peru’s polarized politics, echoing the 2016 results when Keiko Fujimori lost to Pedro Pablo Kuczynski by 0.2 percent of the vote. However, what is novel about this year’s results is how stark the regional divisions of the vote have become with regions in the south, such as Ayacucho, Puno and Cusco voting for Castillo at more than 80 percent, while Fujimori dominated vote-rich Lima with more than 60 percent of the vote. Given the extremely close results, it seems likely that whoever loses the election will contest the results and claim fraud, which will likely lead to bouts of social unrest. However, it is unlikely that claims of fraud will be seen as legitimate, given the presence of international observers and the electoral authorities being seen as impartial. These results suggest that governance for Peru will be difficult for whoever becomes president, as opposition to their policies will be premised on durable and deepening socioeconomic and regional lines. These deepening divisions likely reflect the impact of the coronavirus crisis, which saw the economy shrink by 11 percent in 2020 and poverty increase by 10 percentage points, erasing all the gains made over the last decade. Castillo’s strong performance shows there is support for more statist policies and greater economic redistribution, but what appears to be more salient is Perú Libre’s base of support in the interior, which overlaps with longstanding ethnic and class divisions as well as divisions over inward- versus outward-oriented growth.”

Luis Miguel Castilla, former Peruvian ambassador to the United States and former economy minister of Peru: “The new administration’s capability to deliver the changes demanded by half of Peruvians will depend on building a political coalition in an ideologically polarized Congress (where no party has a majority) and on the capacity to assemble a cabinet that is experienced enough to tackle an ongoing vaccination process and avoid derailing economic recovery. In the short run, the need to contain market panic (in the case of a victory by Castillo) should moderate extreme positions by announcing key appointments. In either case, the risk of social conflict remains high and will constrain future margins of action and recovery of confidence. This may be heightened by electoral authorities’ resolution of more than 300,000 contested votes. In previous runoff elections, 153,000 votes (2011) and 76,000 votes (2016) were annulled. Electoral results give a clear message that most Peruvians expect real changes to reduce Lima’s excessive centralism and disconnection with the rest of the country, improve the quality and access to basic services, boost an insufficient social protection network and repudiate traditional elites tarnished by corruption and populism. Regardless of who wins, Peru’s outlook will depend on respecting constitutional democratic rules and, at the same time, being able to deliver on promises of change. Insisting on a new constitution as a silver bullet to address longstanding structural challenges may lead to a process of even further instability and social setbacks. Unfulfilled expectations are the biggest threat faced by Peru’s democracy and prospects.”

Mariana Zepeda, Latin America research analyst at FrontierView: “As expected, margins in Peru’s presidential elections are razor-thin, and it may be days before results are finalized. While current trends favor Pedro Castillo, it remains unclear who will ultimately win the presidency. Keiko Fujimori and Castillo each appealed to fewer than 20 percent of voters in the first round, and the support they have amassed for the second round has been driven less by ideology and more by fear, leaving voters to grapple with whether they are more worried about the concerns associated with Fujimorismo’s human rights abuses and the corruption cases that have plagued Fujimori and her party, or Castillo’s hard-left positions. What has been clear since the first round is that whoever wins will face a fractured country, where the president’s ability to govern will be limited by a splintered Congress, an economy shattered by Covid-19, a difficult health situation and an unlikely scenario that keeps commodities in a bull market. It is also clear that Peru is on the verge of social unrest. Peru has the world’s highest per capita Covid-19 death toll, and last year’s 11.1 percent GDP contraction plunged some three million more people into poverty. Not only did the pandemic exacerbate class and geographic divisions, it also laid bare years of chronic underinvestment in Peru’s public services. Peru’s political crisis is far from over, and no matter who wins the race, the country faces a difficult path ahead.”

Beatriz Llanos, political analyst: “Neither Castillo nor Fujimori will have a majority in the fragmented Congress, in a country with little culture of political dialogue. Governance is likely to remain unstable, as it has been for the past five years. Both political sectors could be trapped in the win-lose logic that has turned politics into a zero-sum game. The people want change. We will see whether lessons have been learned and whether there is an awareness of the magnitude of the crisis if agreements on several key areas are reached despite the great differences between the two sides, and if they are willing to move forward by accepting opposing viewpoints and moderating maximalist positions. The next president must understand that he or she comprises sectors that need to dialogue with the opposing side. Structural inequality, excessive Lima centralism and unsatisfied rights—exacerbated by the pandemic—of citizens in regions where Castillo has won all point toward a revision of the status quo. It remains to be seen whether Castillo will moderate his statism and distrust of private investment, or if he will accentuate them. It is also unclear whether Fujimori understands the insufficiency of neoliberal immobility focused on macroeconomic growth to generate comprehensive, pro-equality policies. It is not the first time that a presidential election has been won narrowly. The first test for Peruvian democracy will be to accept a result without stirring up claims of fraud.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

Peruvians want an evolution, not a revolution.

Everything you need to know about Peru’s presidential elections.

Insight and analysis into an unpredictable presidential contest

Supporters of socialist Pedro Castillo took to the streets on Monday to claim fraud. // Photo: Facebook Page of Pedro Castillo.

Supporters of socialist Pedro Castillo took to the streets on Monday to claim fraud. // Photo: Facebook Page of Pedro Castillo.

Video

Video