Impact of Lower Commodity Prices on Latin American Growth

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

Dating back to the colonial heydays of Potosí and Ouro Preto, South America’s history has long been shaped by its abundant supply of natural resources. The early 2000s have been no exception. Between 2001 and 2011, commodity exports more than doubled in 11 Latin American countries. Global prices for goods such as copper, oil, gold, and natural gas skyrocketed. These economic tailwinds helped propel robust growth coupled with record reductions in poverty, and, in some cases, inequality.

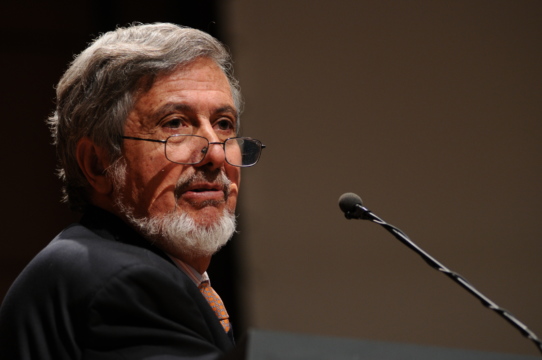

Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela were some of the countries that most benefited from these boom years, asserted Francisco Rodríguez, senior economist at Bank of American Merrill Lynch, during an event hosted by the Inter-American Dialogue. But forecasts indicate trouble may be on the horizon. Commodity prices, though still high, have leveled off. The days of double-digit growth in China, a principal driver of the region’s recent growth, seem to have ended for the time being. Ensuring continued growth and development will fall increasingly on the state, making the decisions of policymakers all the more critical.

Rodríguez commended Colombia’s approach to the natural resource boom, namely, the hesitation to become overly reliant on commodities sales. This was a product of the sharp drop in oil exports the country suffered around the turn of the century. Yet while Colombia may have taken that lesson to heart, pressing challenges remain. José Gonzales, head of ECG Asset Management, pointed to the comparatively high levels of inequality and underdevelopment in Colombia, particularly in the countryside. He cited the recent protests by rural workers as an indicator that the public is growing increasingly intolerant of growth that excludes the country’s poor.

In contrast to Colombia, Peru seems less willing and able to deviate from an economic model that heavily favors mining exports. Though market reforms in the 1990s were certainly an important factor in ushering the country’s economic expansion, high mineral prices have played a larger role than productivity gains, asserted Rodríguez. Both panelists noted that Peru’s fractured political system, virtually devoid of functioning parties, made it more challenging to address the coming slowdown.

The greatest disagreement, however, came during discussion on Venezuela. Gonzales was generally pessimistic of the economic and political situation, citing stunningly high inflation, declining oil production, food scarcities and intense polarization. Rodríguez, while recognizing these problems, noted that there were several low-hanging fruit currently available to President Nicolás Maduro. These included: remedying price distortions resulting from exchange controls, investing oil profits in productivity gains rather using them to finance the government, and curtailing the 50 billion dollars in foreign aid that the country has distributed to its allies. The situation is simply so unsustainable, Rodríguez asserted, that leaders will have no choice but to change course.

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

To remain competitive, Brazil will have to revise its regulations and reverse many of the reforms instituted just a few years ago.

Jorge Díaz / CC BY-SA 2.0

Jorge Díaz / CC BY-SA 2.0