The Washington Post & the OAS Secretary General

The OAS needs to be reformed, but the changes need to emerge from accurate analysis of the problems confronting both Latin America and the OAS.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

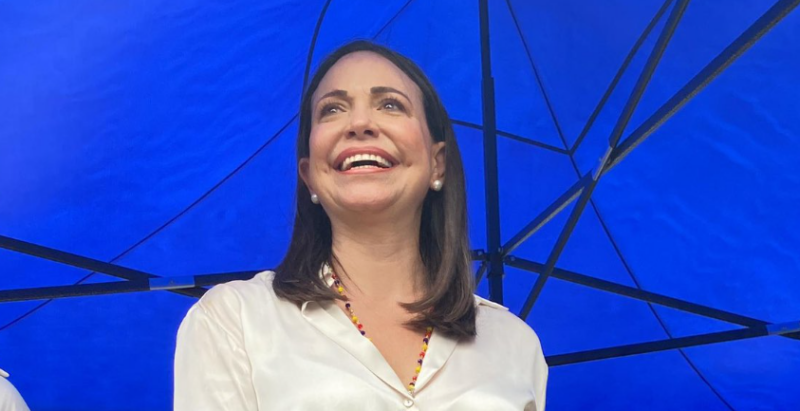

Venezuelans on Oct. 22 nominated María Corina Machado as the opposition’s candidate to challenge President Nicolás Maduro in a presidential election planned for next year. Machado won more than 90 percent of the vote, but Maduro’s government in June banned her from holding public office until 2030, and the country’s Supreme Court on Monday suspended the results of the opposition primary. What is driving support for Machado? Will Maduro’s government, which agreed earlier this month to allow a competitive presidential election next year, allow Machado to run? How big of a chance does Machado have of unseating Maduro next year, and what would she and the opposition need to do in order to achieve that?

Javier Corrales, Dwight W. Morrow 1895 Professor of Political Science at Amherst College: “The irony is too obvious. Here is a government that has conducted the most irregular and non-credible elections for state office in Latin America since the 1980s now accusing the opposition, without proof, of electoral irregularities. Attributing one’s unacceptable behavior to another is the perfect example of projection. Maduro is reminding us that he is not interested in competitive elections. But this is not new information. We have known this since 2016, when he used similar arguments to suspend the opposition-controlled National Assembly and to ban candidates and change the leadership of most parties in the country. Even the communist party has now been ‘intervened’ by Maduro. So it’s not just Machado who is banned. The key question is what prompted Maduro to suspend the primaries, knowing that it came with a new risk: the potential for reversing the recent U.S. decision to ease some sanctions on Venezuela. Perhaps Maduro thinks that the United States won’t react. Or perhaps Maduro concluded that poverty is better than defeat. The primaries were too revealing for Maduro. They demonstrated that no matter how much he spends on electoral clientelism, it would not be enough to secure a victory. The electorate is too excited, too angry, too united and too ready to vote. Maduro read the situation well: he just cannot stop this electoral tsunami with the old-fashioned Chavista tool of clientelism—which is how he planned to spend resources from eased sanctions. My guess is that once Maduro realized the futility of electoral spending (thank you, primaries), the value of sanctions relief declined in his mind, and hence his arremetida (attack). Maduro’s motto seems to be: Poverty is better than defeat, electoral threats are better than fair competition, and sanctions are better than good relations with the United States.”

Julia Buxton, British Academy Global Professor at the University of Manchester: “The primary was more a coronation than contest. Machado faced no serious competition after Henrique Capriles withdrew. Voting for any other candidate was a ‘wasted’ vote given the single round, first past the post system used. Machado does draw a positive vote: she is endorsed as a tenacious resister of the Maduro government, and of Chávez before that. Her economic, energy and other policy proposals appeal to those exhausted by corruption, bureaucracy and inefficiency; and she has broken the ossified discourse of recent years, for example discussing women’s reproductive rights. She is also popular with the negative ‘ABC’ vote ‘Anything But Chavismo’ – a more fragile support base, but one that seems to incorporate traditional government loyalists. The extent to which the disputed 500,000 to 2.5 million voters in the primary represent a wider national endorsement of Machado is debatable. She has her downsides, and they will be exacerbated by the interpretation that she has overwhelming popular support. Her reluctance to compromise, inattention to alliance building and focus on personality rather than political party building are key weaknesses. And she is barred from holding public office after victory in a primary contest now suspended by the Supreme Court. It is not expected that the Maduro government will relent on lifting the ban, not without intense pressure from the United States and other external dialogue partners. Currently, Venezuela, and any defense of Machado, is simply not an arena to which the United States or European Union can commit capacity or energies.”

Will Freeman, Fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations: “Several factors propelled María Corina Machado to become the opposition front-runner. She stayed in Venezuela while many other opposition figures fled political persecution and avoided associating herself with Juan Guaidó’s discredited interim government. Additionally, many Venezuelans support her proposals to reduce the role of the state in the economy, and she has moderated some of her more radical positions. Her disqualification from electoral competition earlier this year also seems to have given her campaign momentum. The Maduro regime is unlikely to allow Machado – its most popular opponent - to run, as is already clear from the regime’s reaction to her primary win, which can be summed up as damage control. The Supreme Court has already suspended the results of the opposition primary, and Public Prosecutor Tarek William Saab says he will probe the results of the vote for fraud. Regime officials understand Machado would win in a free and fair contest, and possibly even have enough popular support to prevail on a tilted playing field. A recent survey by Poder y Estrategia shows that Machado had strong majorities across all segments of Venezuelan society. A survey by ORC Consultores showed a similar advantage for Machado. Latin America’s transitions from military dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s were often led by civilian figures seen as palatable, or at least not openly threatening, by military juntas. If Venezuela were to experience any kind of transition, it’s likely that a figure less threatening to regime interests would end up at the helm.”

Phil Gunson, Senior Analyst for the Andes region at International Crisis Group: “There is an overwhelming desire for change among Venezuelan voters, both among chavistas and the opposition. Machado, as a relative outsider with a bold and uncompromising style, was the only candidate on the primary ballot who really represented that. Her stunning victory, and the unexpectedly large turnout, makes it even less likely that the government will lift the ban on her candidacy. In a free and fair election, as things stand now, Maduro would lose badly in a head-to-head with Machado, and he does not plan to give up power. But Machado’s ban alone will not suffice. In the Barinas state gubernatorial election in 2021, the opposition won with an increased majority in a rerun after several candidates were successively banned, including the original winner. So the government will do all it can to split the opposition and promote abstentionism by encouraging the belief that voting is pointless. The challenge for the opposition is to remain united around an electoral strategy and campaign for the best conditions possible under the circumstances. While determined to win, Maduro would still prefer to reap the benefits, both economic and diplomatic, of holding an internationally recognized election.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The OAS needs to be reformed, but the changes need to emerge from accurate analysis of the problems confronting both Latin America and the OAS.

By all accounts, Spain wants to bring change to the European Union’s Cuba policy. In so doing, it is tackling a foreign policy challenge that often sheds more heat than light.

Although politics has cyclical features, and ideology is sometimes a factor in choices made by Latin American voters, the left-right labels obscure more than they illuminate.

María Corina Machado overwhelmingly won the Venezuelan opposition’s Oct. 22 primary. But the government has barred her from holding office, and the Supreme Court suspended the primary results. //

María Corina Machado overwhelmingly won the Venezuelan opposition’s Oct. 22 primary. But the government has barred her from holding office, and the Supreme Court suspended the primary results. //