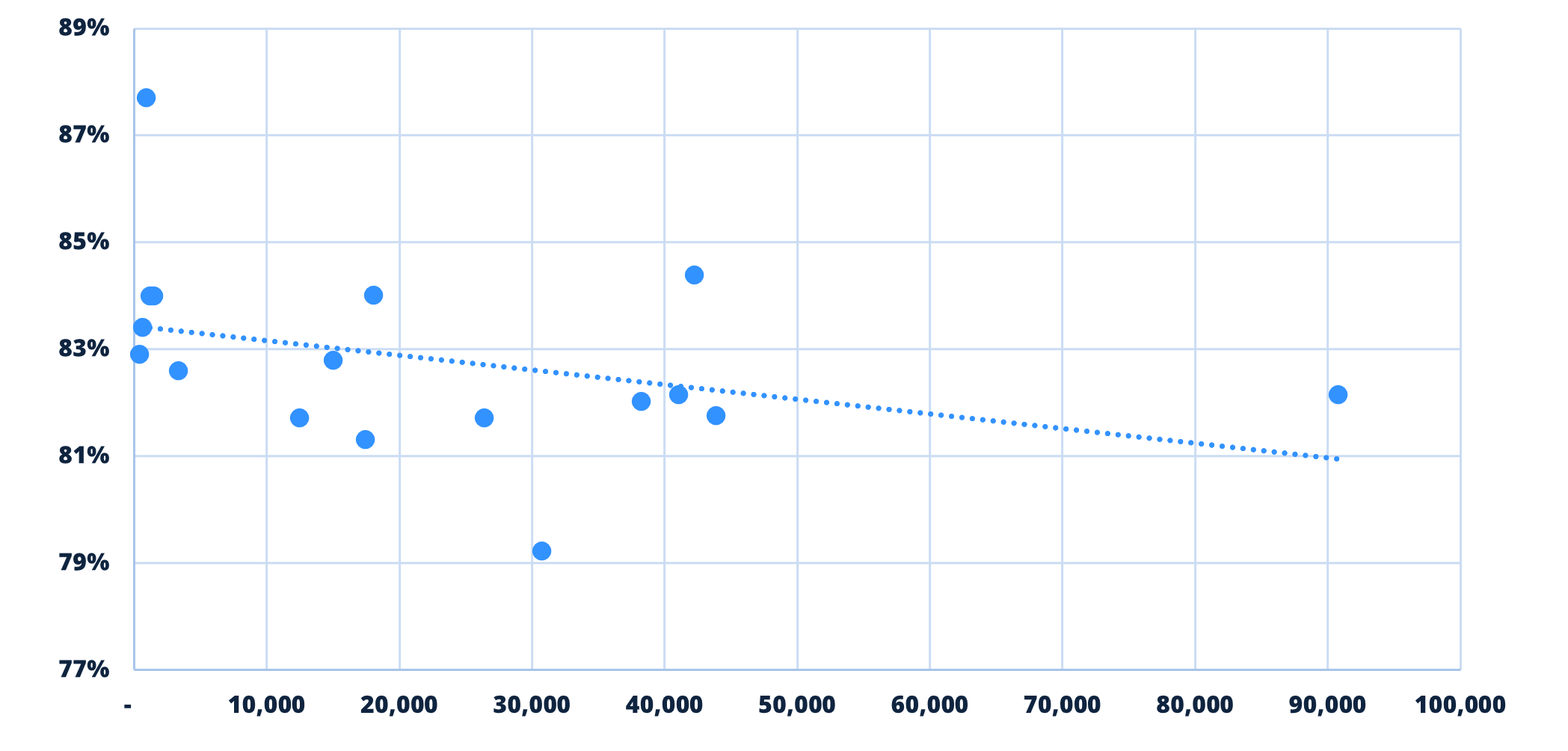

The Ortega and Murillo dictatorship has used migration as a weapon against the United States and a tool of state capture.

First, the dictatorship’s continued expulsion of Nicaraguan citizens has increased the burden of the current migration crisis. Second, economic opportunism behind this expulsion in the form of remittances has strengthened state capture led by the Ortega-Murillo family clan. Third, the regime’s role in using the country as a conduit of irregular migration is being used as a foreign policy tool against the United States.

Nicaraguan Migration in 2023

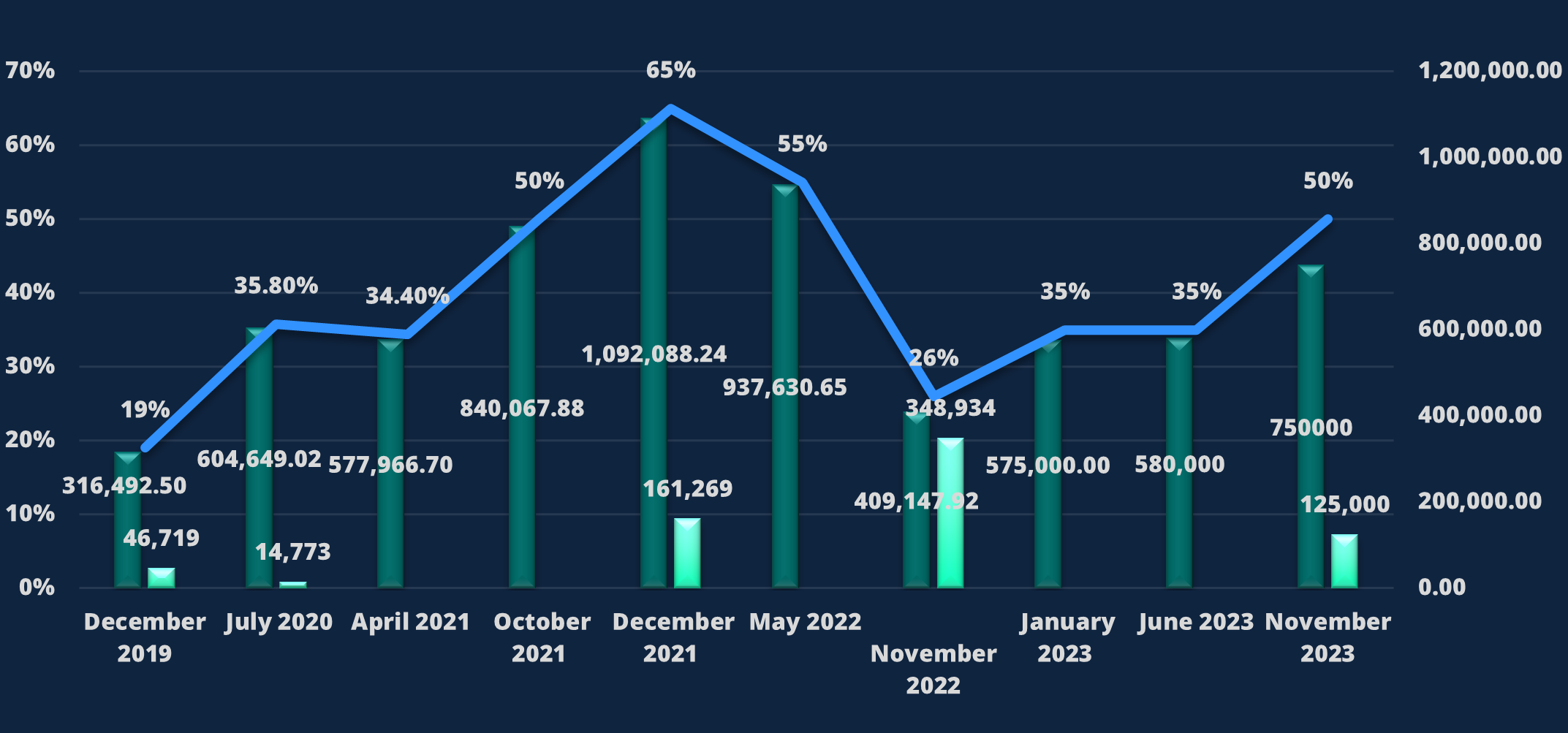

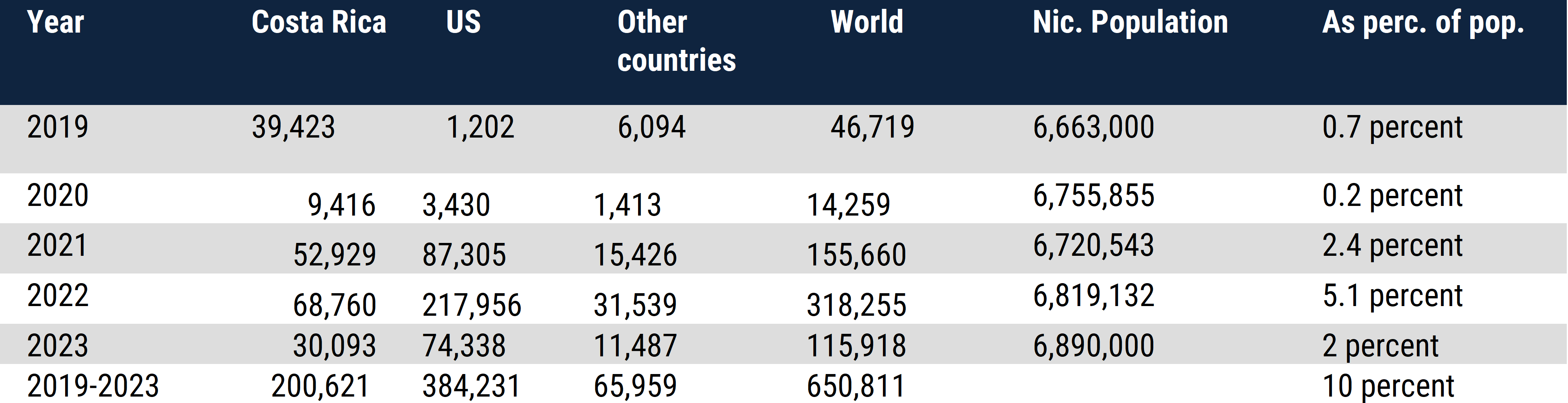

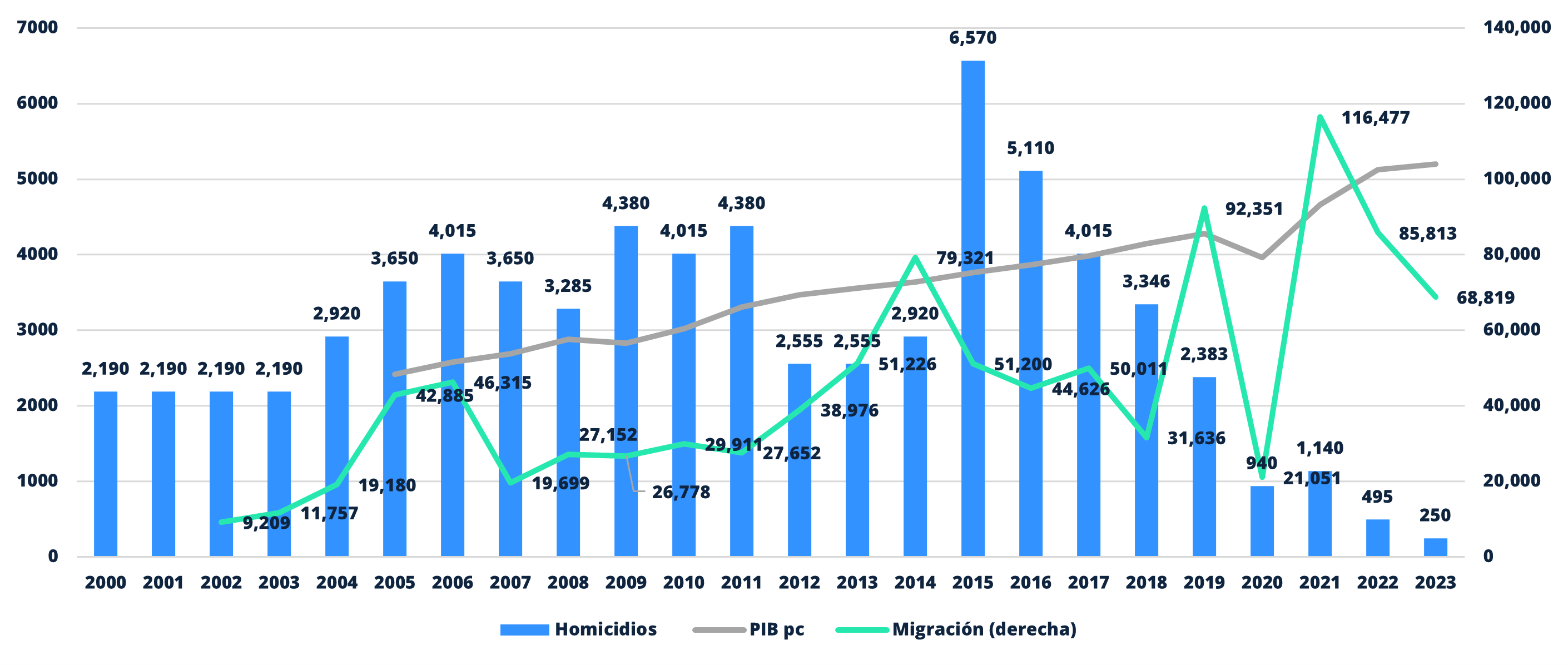

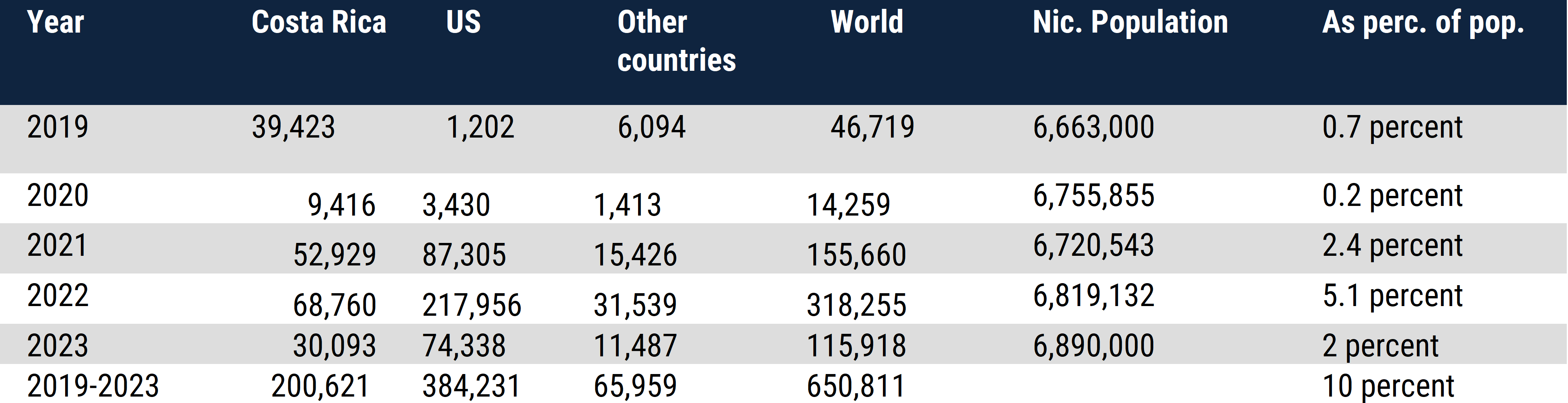

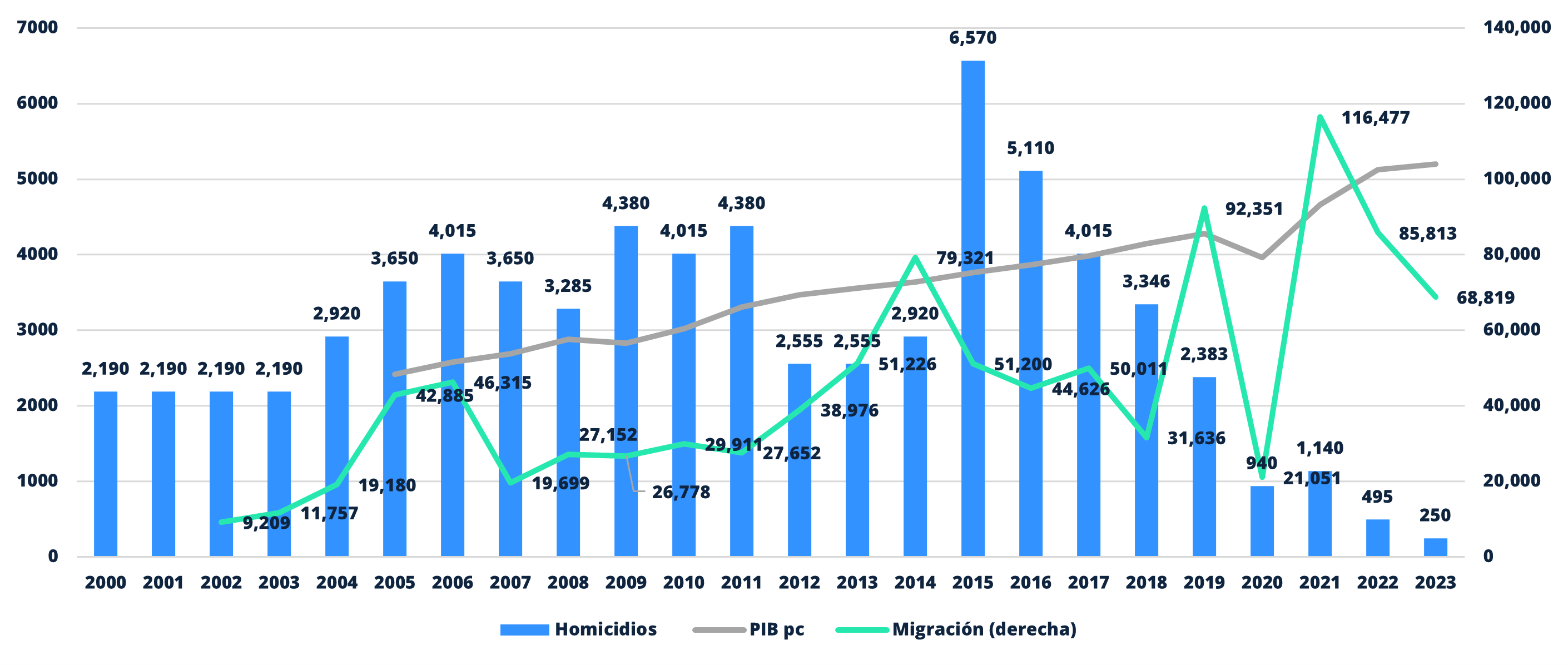

In 2023, the migration trend among Nicaraguans equated to two percent of its total population and four percent of the labor force. These numbers are lower than in 2022 and are associated with several realities. Once the parole was established in January 2023, the number of people who could leave decreased because the policy signaled that migration was only possible through humanitarian parole. However, bringing people under the parole has an emigration ceiling: the number of Nicaraguans legally capable of sponsoring someone with them is no more than 90,000 people. There are already 50,000 beneficiaries of parole.

Second, the economic burden on adults in Nicaragua who are in the labor force has increased since 2018. Now, the labor force comprises less than 45 percent of the population and as the burden to workers increases, the costs of emigrating and leaving families alone are higher. This mitigates the decision to migrate since it becomes more difficult to leave a family member in the hands of third parties.

However, the intention to migrate continues to be high. Those seeking to migrate belong to all social strata and groups, whether they are pro-government or not. Furthermore, the intention continues to be justified by political rather than economic reasons.

An analysis of the CID-Gallup survey of November 2023 shows a statistical correlation between the intention to migrate and the political conditions in Nicaragua. Those who want elections, free political and religious prisoners, and an end to the police state, exhibit a probability of 1.83 times more likely to emigrate than those who do not want to leave. Those who believe that the country is going in the wrong direction exhibit 2.86 times more intention to migrate. Also, men and those who are older and educated have a greater intention to migrate. Economic indicators do not statistically correlate with the intention to migrate. The problem is political.

These realities highlight that, in 2024, people will continue to emigrate in similar numbers to 2023, possibly in families. This situation is similar to what is happening in the rest of northern Central America and Mexico. People are not migrating alone, 50 percent of those migrating from the Northern Triangle travel as a family group. This situation will intertwine with how immigration policies in the United States develop during the electoral season and how migration is viewed as a foreign policy issue.

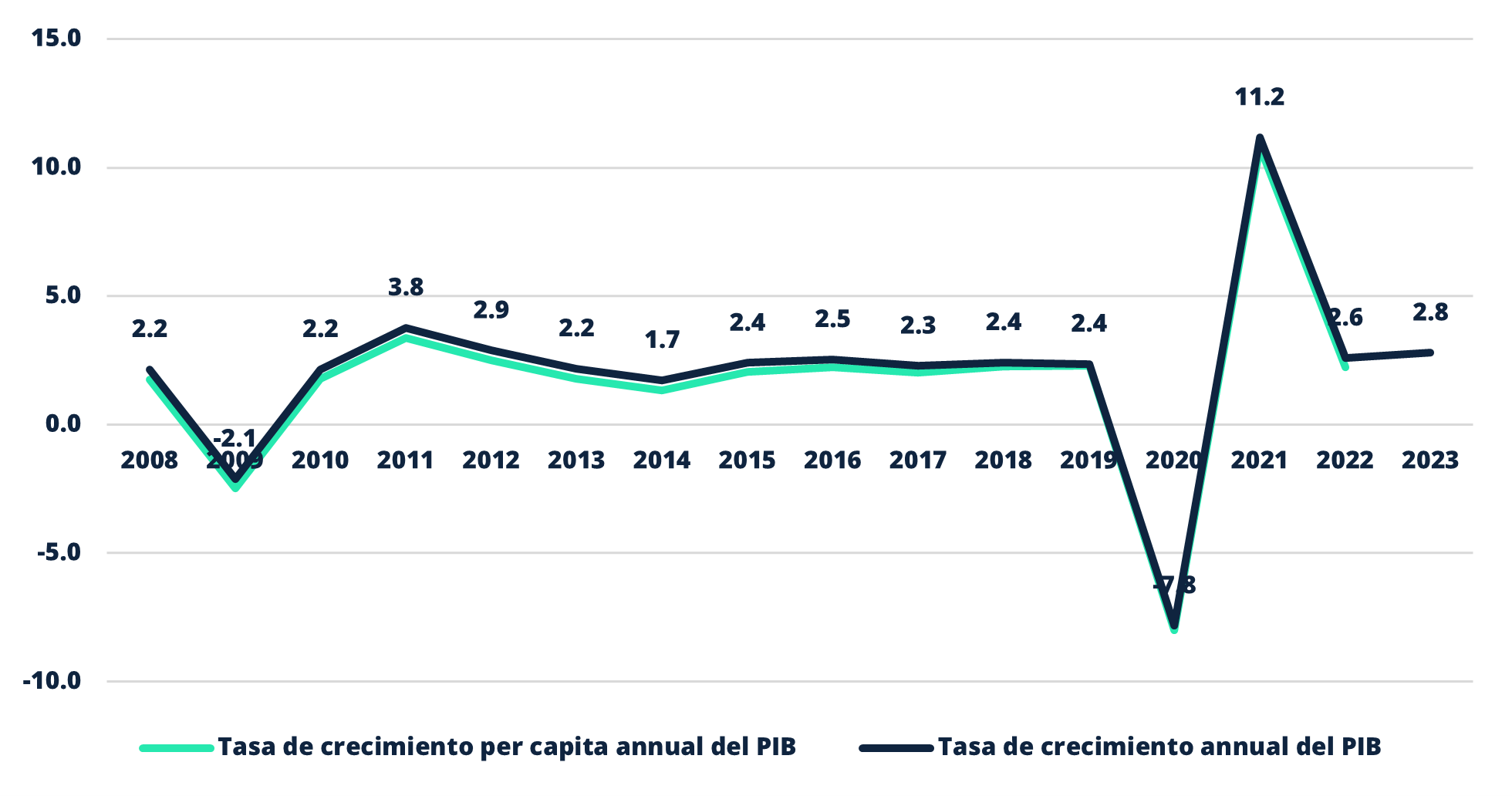

Graph 1: Percent of People with an Intention to Migrate

Source: Public opinion surveys from CID-Gallup, Borge and Associates.

Table 1: Nicaraguan Migration

Source: Author’s projections based on official statistics from immigration authorities in the US and Costa Rica.

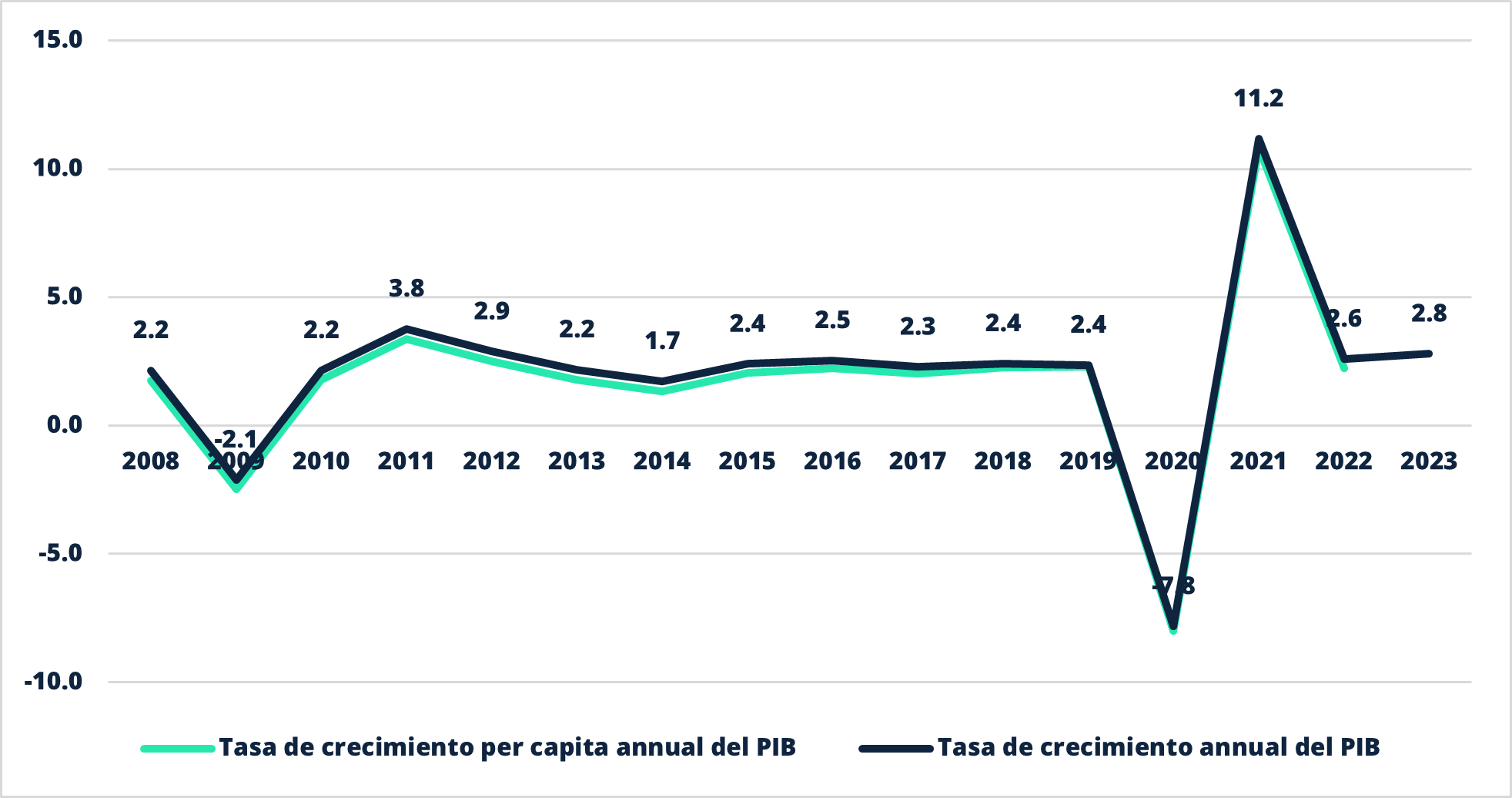

The Medium and Long-term Social and Economic Effect of Migration

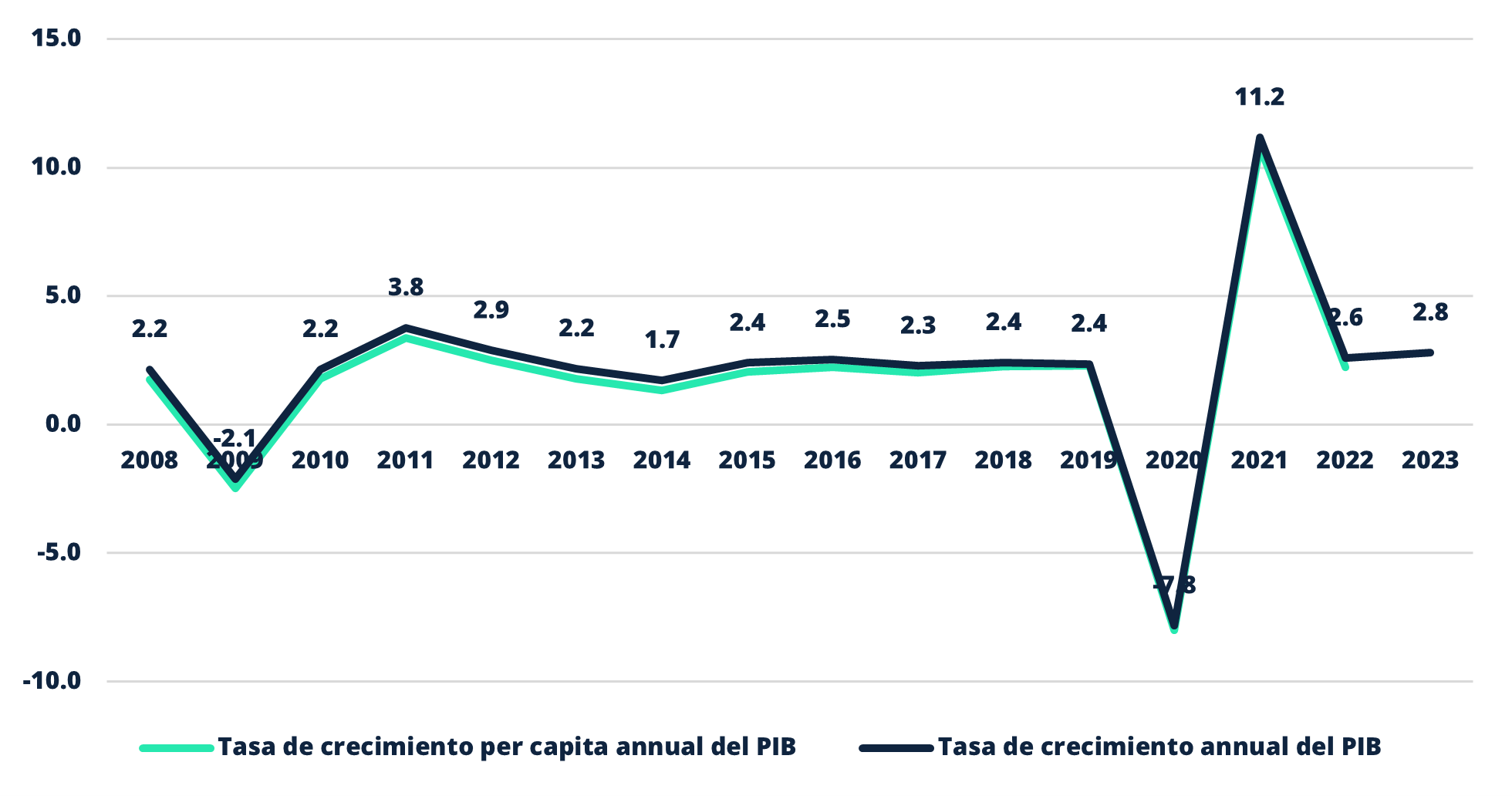

For most developing countries, Nicaragua included, migration is an escape valve from the few options available to improve the quality of life and the material and political circumstances provided by these countries’ economic models. Governments pay attention to the external sector through models that are nonproductive (use of low-cost labor to work in textile manufacturing, mining, agro-exports or tourism) while excluding (these methods do not absorb more than 25 percent of the workforce, but they generate more than half of the country’s wealth through a network of oligopolies).

The rest of the labor sector is stuck in the informal economy.

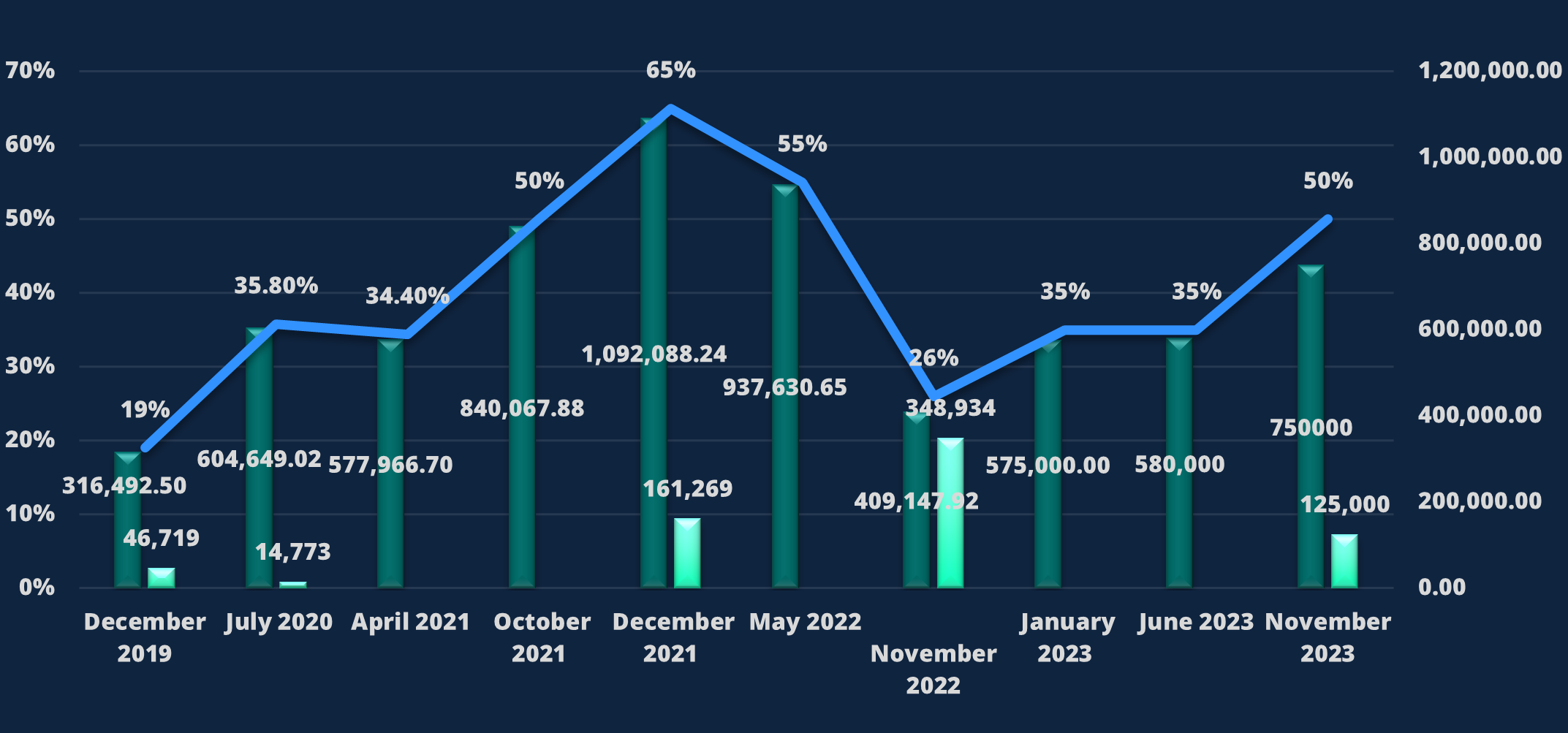

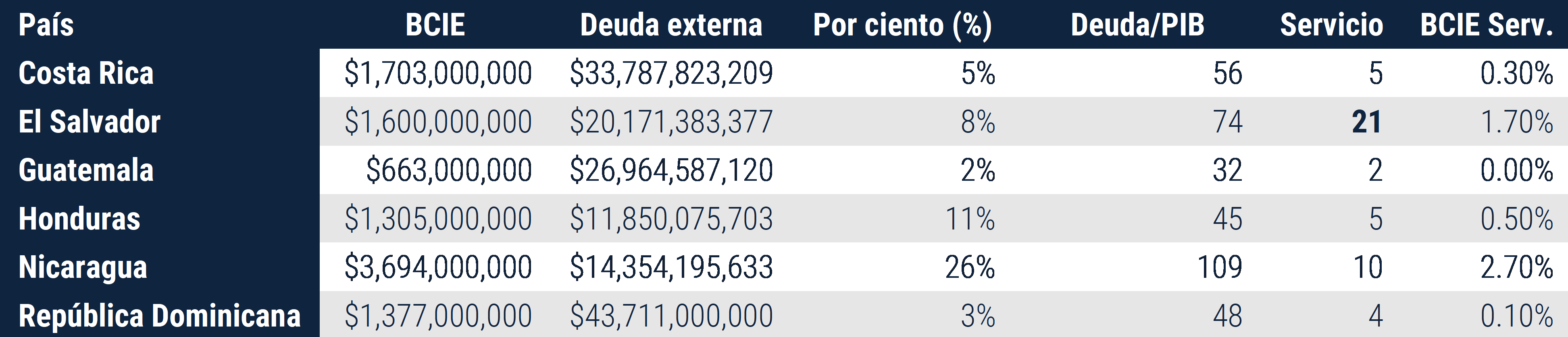

The more migration there is, the more remittances arrive. This money helps compensate for the lack of income and improve consumption and savings capacity. In a totalitarian society like Nicaragua there is ‘state capture,’ where expulsion of people is part of an economic pillar supporting the political system (extortion, clientelism, corruption, confiscation, are the other pillars). In the realm of state capture, remittances are vital for the clan leading the capture. This pattern thus creates a dependency on migrants and future income.

Currently, remittances represent 20 percent of the tax revenue and 33 percent of private national consumption. This is a double-edged sword, because migrants can make decisions about how to control money and have direct effects on the state. The trend in 2024 does not foresee a large departure of Nicaraguans, and if it and if it does occur, it will be in family groups. This will mean that the growth of remittances will ‘normalize’ below 10 percent. However, the dependence of tax income on remittances will remain fixed, and, in the face of state capture, the population will notice how their taxes further fuel corruption, a situation that discourages increasing consumption or investment and can even reduce amount of money transferred by migrants.

Graph 2: Private Consumption (US$,000,000) [right] and Remittances Share of It (%) [left]

Source: Central Bank of Nicaragua

Graph 3: Taxes (US$,000,000) [left] and the Share of Remittances [right]

Source: Central Bank of Nicaragua

Weaponizing Migration as Foreign Policy

The third axis of the regime is one of ‘weaponizing’ migration to damage the United States. First, the regime’s political elite changed tactics concerning the migration of Cubans and other nationalities, taking advantage of the high number of people of varied nationalities who were fleeing their countries.

A reality of the post-pandemic period is that 18 countries (China, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Mexico, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, and Venezuela) represent 92 percent of all irregular migration that reaches the border with Mexico.

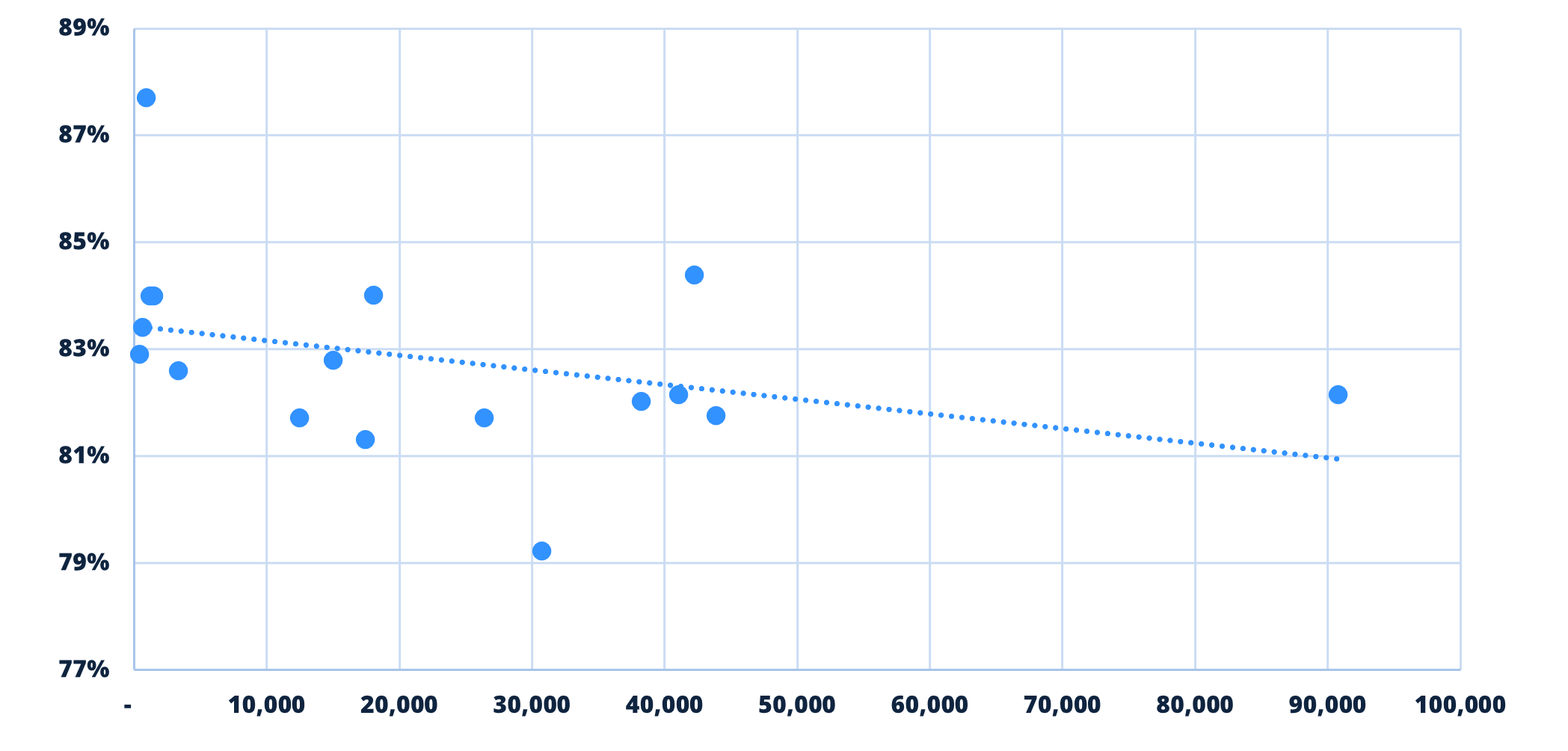

None of these migrants come from politically stable countries, where the rule of law predominates, or where there is freedom of expression. Every country is below the world average or median of the World Bank’s governance indicator. For their part, Nicaraguans are now four percent of all migration that left to the United States between August 2020 and December 2023. Moreover, the share of these nationalities’ arrivals and weak governance is visible.

Graph 4: Governance and Migration to the US Border

Source: World Bank Governance Indicators (lower number indicates lower governance) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Nationwide Encounters.

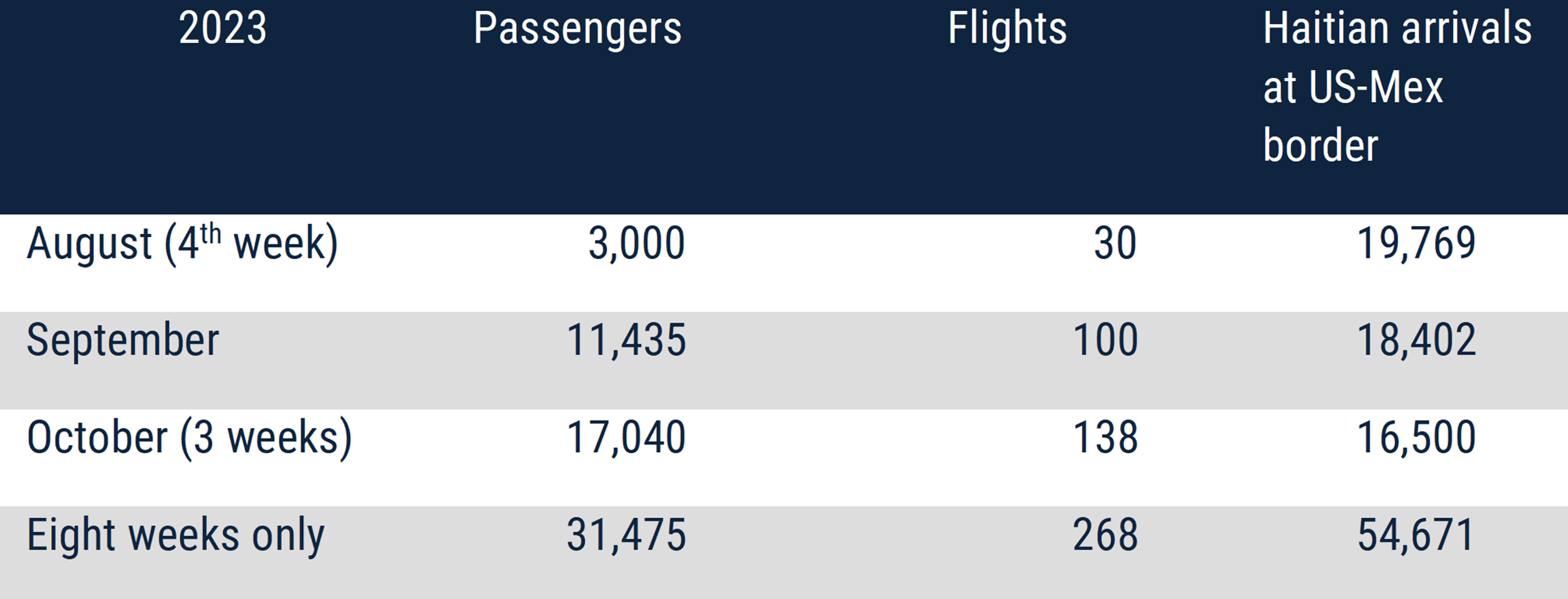

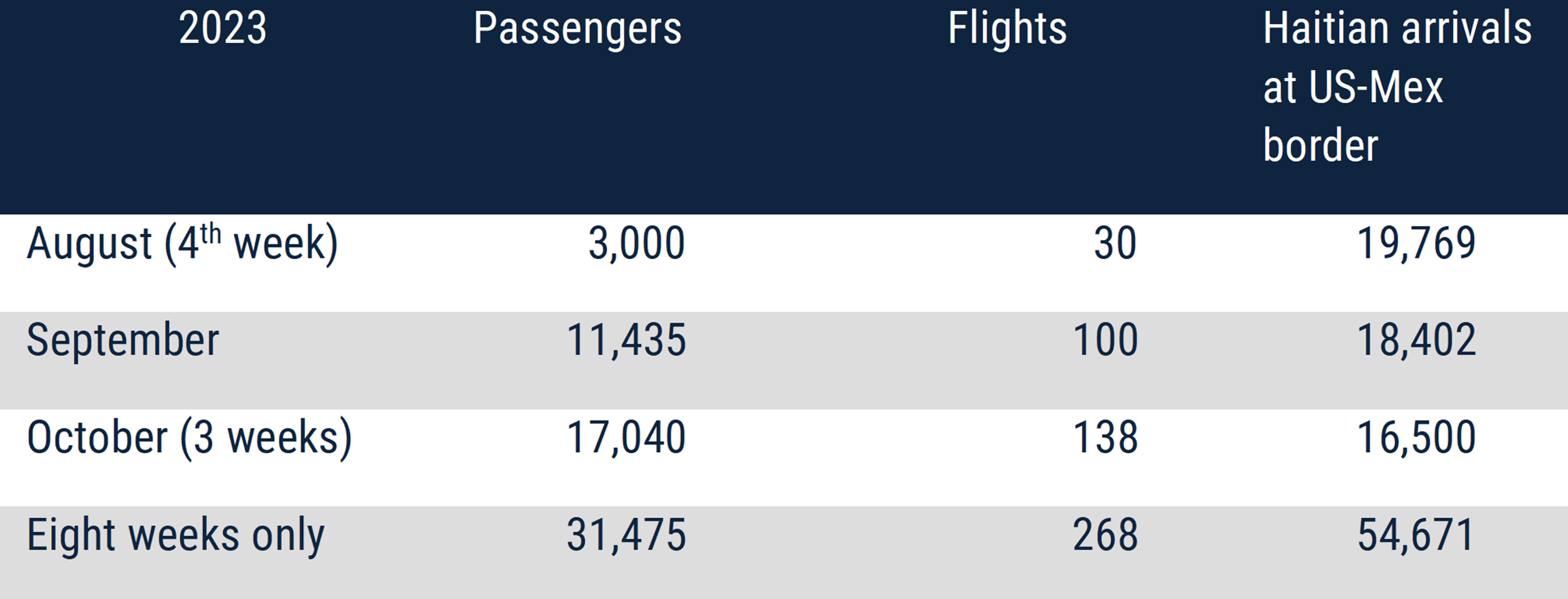

The family clan identified these nationalities and took advantage of the economic and political opportunity to ‘weaponize’ migration as a foreign policy against the United States and increased the weight of the humanitarian crisis. The regime began by eliminating restrictions on Cubans and in 2023, it eliminated visa restrictions on several nationalities, including Haitians.

In April 2023, the government hired a Dubai-based company to train the Nicaraguan civil aviation team to manage immigration procedures for passengers on charter flights. The result is that between June 2023 and November 2023 there were more than five hundred charter flights, increasing the arrival and departure of flights from 45 to 93 and generating a transit from Nicaragua of more than 100,000 passengers from Port-au-Prince, Havana, and Providenciales to Managua to make the journey to the United States.

This decision also risked the potential for criminals and terrorists to sneak among those passengers and reach the United States border. Although the Biden administration momentarily stopped this form of aggression, Nicaragua has wanted to continue down this path and took advantage of the opportunity to facilitate the passage of foreigners from India from Dubai on three occasions in a way that facilitated their journey.

Table 2: Direct Flights from Port Au Prince to Managua

Source: DHS; https://www.flightaware.com/live/airport/MUHA/departures;

Graph 5: Daily Flights to and from Nicaragua

Source: FlightAware

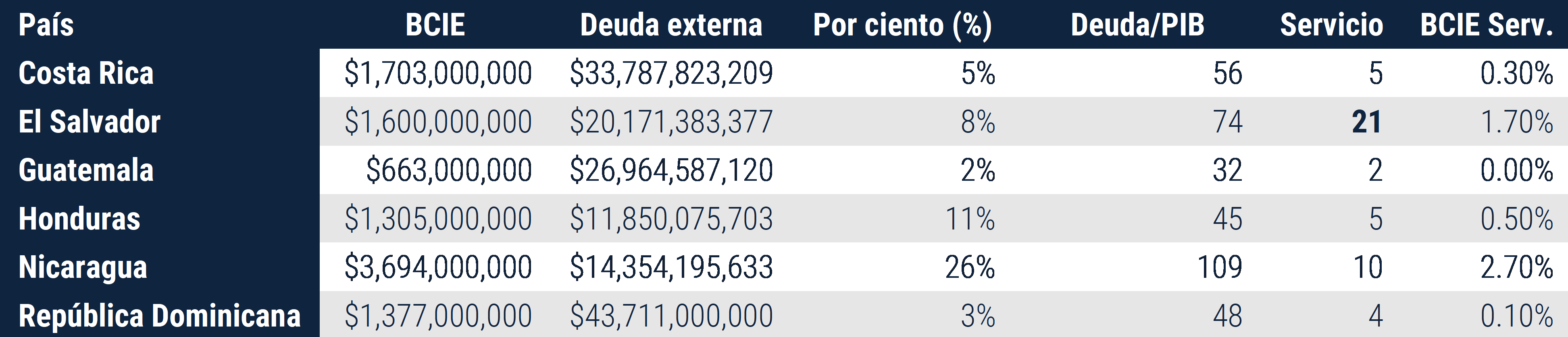

Moral Hazard and Miscalculation in US Foreign Policy

Migration is a foreign policy problem. While Ortega has taken advantage of migration as a weapon of attack against the democratic spirit and international law, the United States has avoided antagonizing its relationship with this state. One of the reasons that has been given is that using sanctions as a policy generates an adverse economic impact on the population, which could translate into emigration.

The reality is entirely the opposite.

Although the opinion that international sanctions has had an effect on oil production in Venezuela is commonly accepted, the data contrasts with reality. The drop in Venezuelan oil exports precedes sanctions against the country and is more aligned with the realities following the economic disaster that Hugo Chávez created in 2014.

What the so-called sanctions relief in 2023 allowed is the legitimization of Maduro’s attempt to hold elections under noncompetitive conditions with a weakened opposition. Indirectly, the United States is playing into Maduro’s hands. Even if the reason for the relief is strictly in the economic interest of the United States, Venezuela will not be able to increase its oil exports in the short-term, even more so when Guyana’s oil output is already competing with Venezuela. While sanctions have declined, more migration has occurred.

Graph 6: US Sanctions and Oil Production in Venezuela

Source: US Treasury and Oil production data from Trading economics

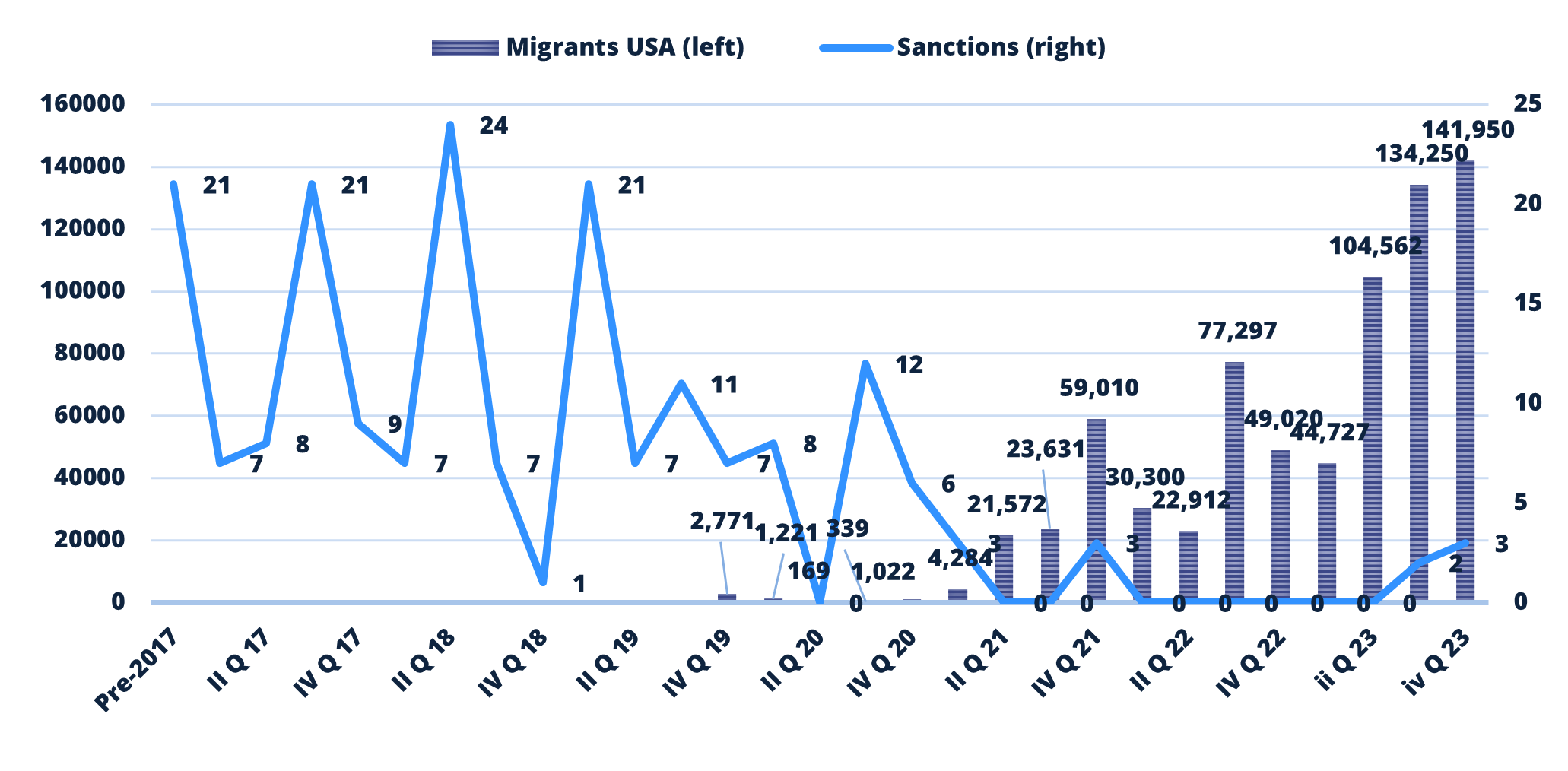

Graph 7: Sanctions and Venezuelan Migration to the US

Source: US Treasury and DHS Nationwide Encounters

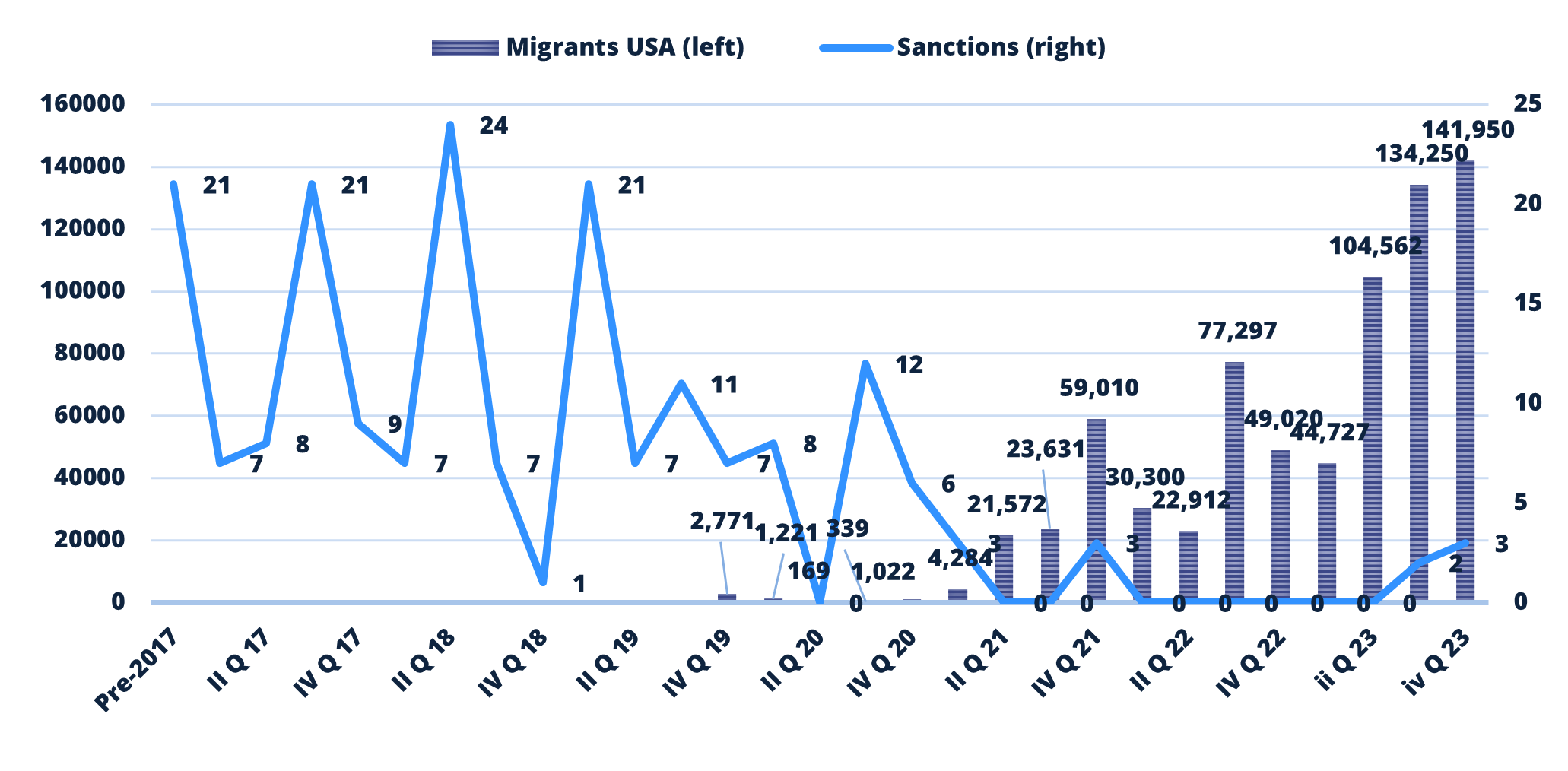

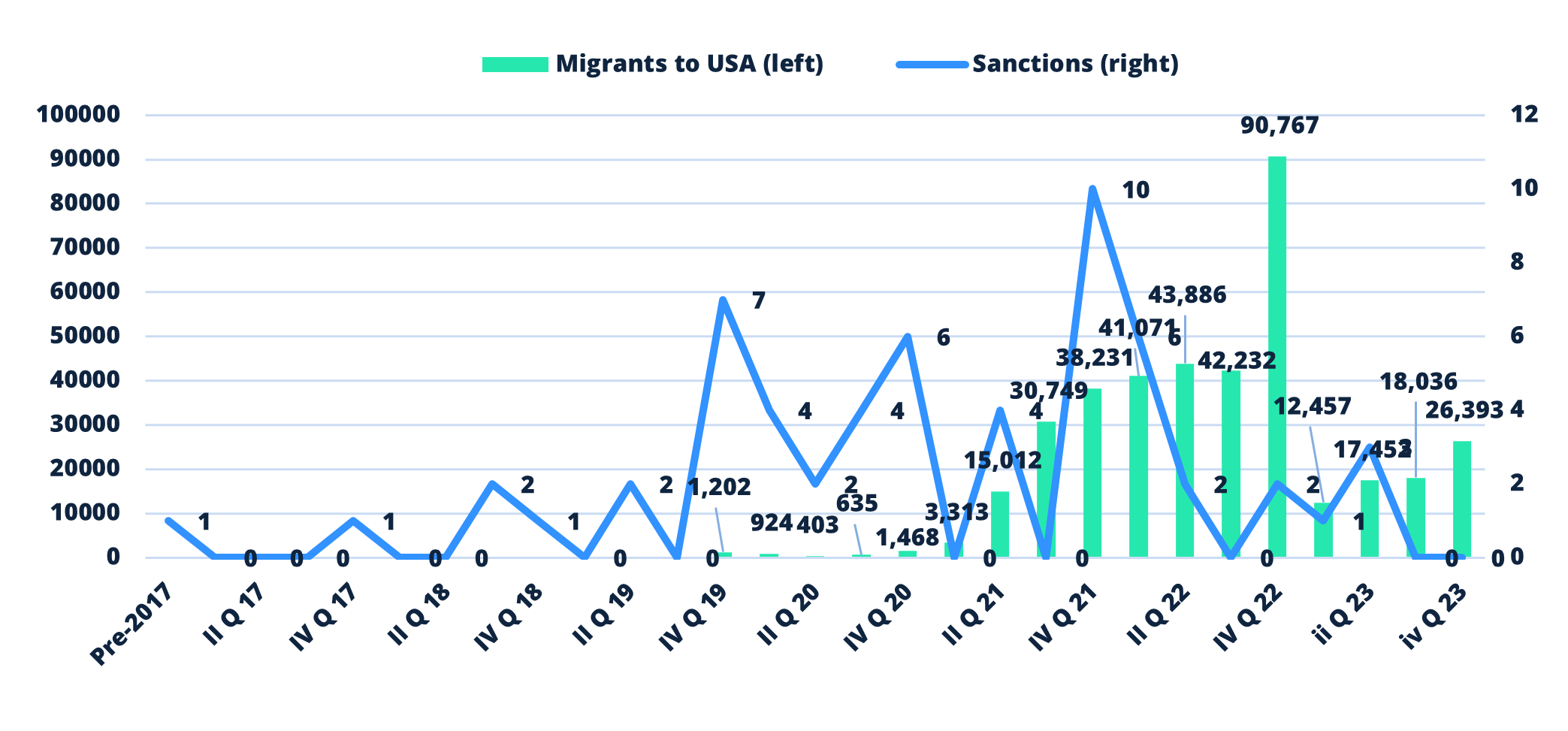

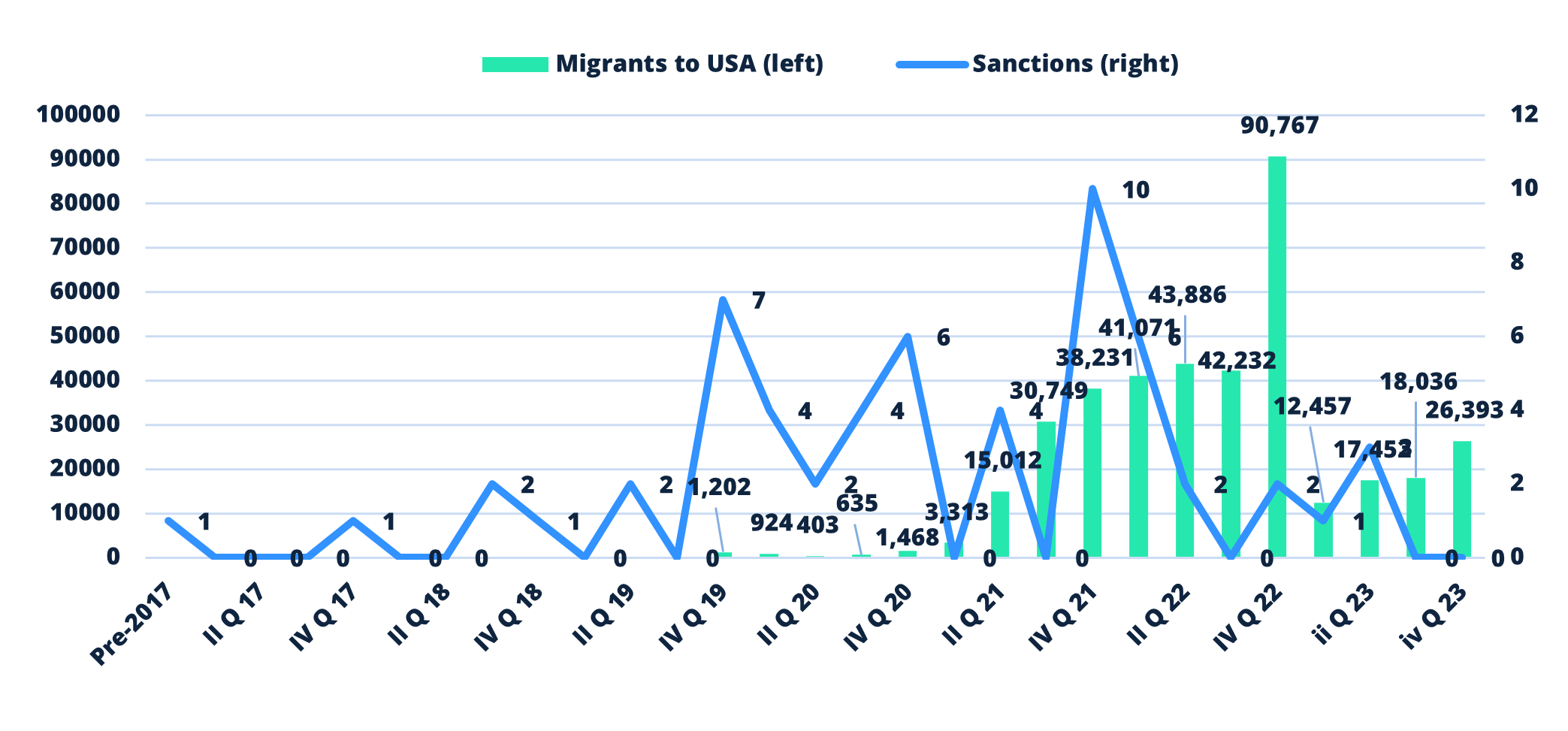

The same reality is observed with Nicaragua. Sanctions on the transgressors of Nicaraguan citizen rights have had the effect of minimizing the transgressor’s margin of operation and in reducing the number of the regime’s international operators. Contrary to Ortega’s arguments, the absence of sanctions is occurring at a point when there is more repression and emigration. Instead, migration has increased as a result of political factors, investor confidence, and judicial insecurity.

Graph 8: US Sanctions and Nicaraguan Migration to the US

Source: US Treasury and DHS Nationwide Encounters

The political calculation of the United States has been to err on the side of moral risk as opposed to accompanying sanctions with a foreign policy consistent with the impact of these countries on the national interest and democracy priorities of the current administration.

Nicaragua is an emblematic case of how a pariah state is harming the world by increasing migration and supporting the movement of people that exacerbates the migration crisis. The United States must proportionally penalize both Nicaragua’s violations of its international commitments and its attacks on the United States.

Graph 9: Declining Investor Confidence (ratio between private investment and private consumption) and Migration, Q1-2018 to Q4-2023

Source: Banco Central de Nicaragua (ratio of private investment and consumption) and DHS Nationwide Encounters