Growing Chinese Presence & Taiwan’s Influence

Central America is one of Taiwan’s only remaining diplomatic strongholds.

Brandishing torches, skulls, and signs calling for the resignation of the president, nighttime protesters flood the streets of Tegucigalpa. In the months following a corruption scandal which robbed the Honduran Social Security Institute (IHSS) of hundreds of millions of dollars and resulted in a medical supply shortage that caused, according to some, upwards of thousands of deaths, protests have become a regular occurrence. Outraged by evidence of rampant corruption and impunity, Hondurans are demanding change.

The Oposición Indignada (indignant opposition) emerged in early June, after various investigations and medical shortages revealed that inflated contracts allowed officials at the HSSI to funnel roughly $200 million dollars from the Institute. Some of the stolen funds were traced to the ruling National Party’s campaign coffers, meaning that current President Juan Orlando Hernández benefited directly from the scandal—although he has insisted that he had no knowledge whatsoever. This prompted the Indignados movement to call repeatedly for the resignation of Hernández and establishment of an international commission to address corruption and impunity modeled after the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG).

In response, the president agreed to a joint proposal with the Organization of American States for a Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). Comprised of an international panel of judges and prosecutors, the proposed body—agreed upon in theory, but not in specifics—will assist Honduran institutions in fighting corruption, impunity, and insecurity. The joint announcement was met with both support and cynicism. Some view MACCIH as a meaningful step towards reform, while others believe—with good reason—that it is simply a smokescreen aimed at placating protestors while maintaining President Hernández’ hold on power. While the MACCIH proposal is (in theory) a laudable development, there are grounds for skepticism, above all over whether the state is truly committed to reform.

While the social security scandal was a tipping point for many Hondurans, it is merely a part of a long history of institutional weakness. Even before the IHSS scandal, one quarter of Hondurans consistently report personally witnessing acts of corruption every year and over two-thirds viewed state institutions as compromised. The judiciary in particular is widely derided as incompetent, held under lock and key by political forces.

Case in point, during his term as Speaker of the House—immediately before being elected President—Hernández spearheaded an effort to sack and replace four Supreme Court justices for opposing his party’s legislation. Once he assumed the presidency, the Supreme Court justices proceeded to overturn presidential term limits at his request. Then, this past month, a US court indicted members of one of the country’s wealthiest most powerful families—Jaime Rosenthal, a former vice president, his son, and his nephew—on money laundering charges. The case is yet another embarrassment for the troubled justice system: prosecutors in Washington bringing charges while those in Tegucigalpa appear powerless. So far, Hernández has insisted that the case is between the Rosenthals and the United States.

At the same time, crime and violence continue to run rampant. Polls show that 47.9% of Hondurans consider security to be the most important problem. The murder rate in Honduras was 68 per 100,000 people in 2014, making it, by some measures, the most dangerous country in the world. A controversial move by the Hernández government to militarize the police has yielded mixed results and sparked new concerns over extra-judicial proceedings.

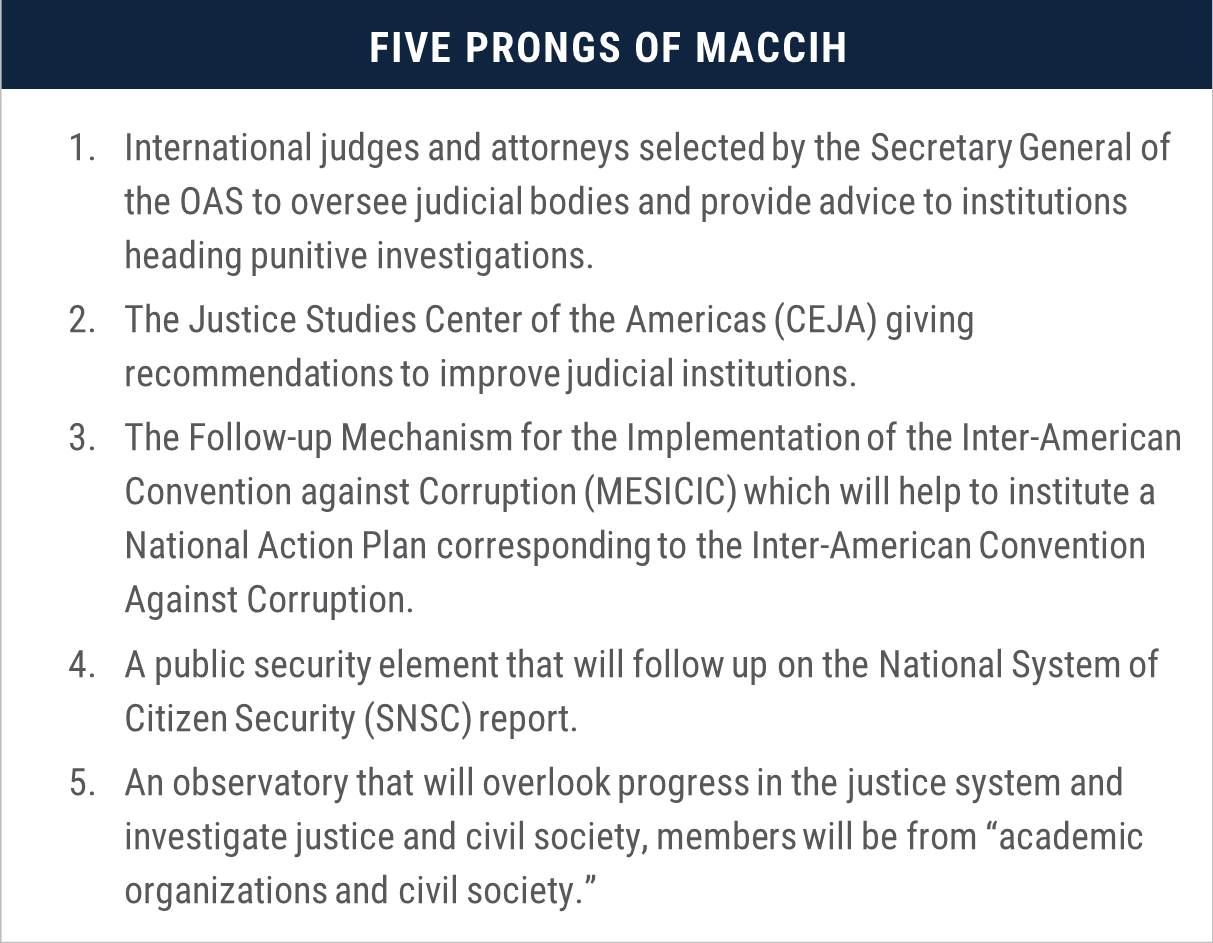

The MACCIH concept is intended to simultaneously address all of these complex and interrelated problems. While its specific powers have yet to be outlined, the proposal is a five-pronged mission to target issues of judicial independence, corruption, and citizen security. The effort will be headed by a Chief of Mission, a yet to be named international legal expert reporting directly to the Secretary General of the OAS. This past week, Honduran authorities traveled to Washington to further negotiate details, while OAS officials will visit Honduras the second week of November.

Whether MACCIH fulfills its intended purpose will be determined by the final agreement between the OAS and the Honduran government. The UN-backed CICIG—a partial model for MACCIH—has been successful in large part because of its specificity, its independence, the extent of its powers, and the high quality of its leadership. Ultimately, CICIG investigations helped lead to the resignation and arrest of Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina. On the surface, the two organizations’ similarities and differences are difficult to discern; MACCIH’s promise will be much clearer once the agreement is finalized.

However, readily apparent differences between the two organizations are reason enough for skepticism. CICIG focuses narrowly on dissolving illegal security forces, combatting organized crime, and supporting the public prosecutor’s office in efforts to clean up illicit finances. In contrast, MACCIH attempts to address many of Honduras’ problems at once. Although there may be benefits to a broader scope, the amorphous mandate of the mission could also prove unwieldy and self-defeating. This concern is magnified by the contrast between CICIG’s current price tag ($12 million annually) and the anticipated cost of MACCIH ($2 million annually). It is doubtful that an organization with significantly less funding than CICIG could be expected to succeed in any case, and certainly not in a much more ambitious undertaking.

Moreover, international efforts can only go so far. The effectiveness of the commission is fundamentally contingent upon a strong commitment from domestic institutions and the ability of those institutions to act independently from the Honduran political sphere. This has largely been the case in Guatemala, where the public prosecutor’s office has worked in close cooperation with CICIG to take on powerful political interests. If MACCIH judges and lawyers do not find willing partners in their Honduran counterparts, then it is hard to imagine the mission will succeed.

Hopefully, the finalized MACCIH mandate will draw upon the structure and powers of the CICIG for inspiration. CICIG’s mandate established separation between the commission and the state. The autonomy to conduct independent investigations, the ability to employ confidentiality to protect staff and witnesses, and the power to request relevant information from any government organization or official and expect full compliance were key aspects of the CICIG’s success. Including the same elements in the MACCIH mandate would encourage a similar impact and reveal the true seriousness of the mission.

However, a portentous omen for Honduras’ commitment to the cause emerged this past week. On October 22nd, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights held hearings on judicial independence and reports of corruption in public institutions in Honduras. The sessions were held in response to complaints brought by a broad coalition of civil society actors. In a surprising and rare move, the chairs on one side of the room were empty.

The Honduran government decided not to show up.

Central America is one of Taiwan’s only remaining diplomatic strongholds.

Second, third, and fourth terms run rampant in Latin America. But are they such a good idea?

Given the huge demands on Washington – domestic and international – and today’s ravaged, fragmented, and leaderless region, this is probably not the right time for bold, ambitious initiatives. But the Biden administration should move quickly to renew partnerships with select countries, emphasizing recovery from Covid-19 and restoring economic and political stability.