Mexico’s Midterm Elections: Politics & Issues

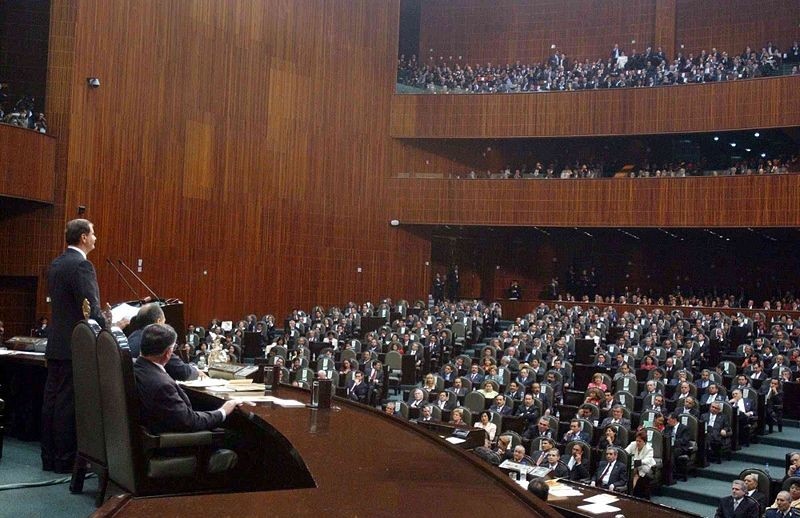

Gustavo Benitez / Public Domain

Gustavo Benitez / Public Domain

Mexico will hold midterm elections this upcoming Sunday, June 7th. Most analysts and pollsters expect the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) to hold its place as the party with the most seats in congress. But behind a seemingly straightforward result lies a series of important questions and implications regarding Mexico’s party system and political future. To discuss this important moment for Mexico, the Dialogue hosted a discussion on June 3rd featuring two of the country’s leading political analysts: Rafael Fernández de Castro and Miguel Basáñez.

Fernández de Castro, a professor of Public Administration and International Affairs at the Maxwell School, kicked off the session by analyzing the factors driving the electoral outcome. Polls predict that the PRI will win close to 190 seats, an outcome similar to that of the previous congressional elections in 2012. The PAN and the PRD, the two other historical protagonists of the Mexican party system, will follow behind, with around 115 and 90 seats, respectively. Fernández pointed out that the performance of smaller parties, like the Partido Verde (PV) and Morena, should not be ignored: the PV is a close ally to the PRI, and together they will account for almost 50% of the seats in Congress that are required to rule by majority; Morena, a leftist party founded by the popular politician and two-time presidential candidate Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, will win close to 25 seats, the largest congressional debut of any new party in a federal election. Morena’s consolidation into the Mexican political system will have long-lasting effects as the left continues to diversify closer to the 2018 presidential elections.

For some, the PRI’s comfortable ride to victory may come as a surprise, given the deteriorating security and corruption issues that exist in the country. The disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa, the first lady’s “White House” scandal, and the cancellation of infrastructure projects like the Queretaro train, have sparked massive protests all around the country and radically transformed the positive, reformist image that characterized the Peña Nieto administration between 2012 and 2014. Fernández de Castro explained some of the factors that will contribute to the PRI’s likely victory. First, despite the difficulties that Peña Nieto has been facing recently, the government has opted for a strategy where “indignation runs its course” and frustrations die out. The economy also helps explain the trends: even if it hasn’t performed spectacularly, economic growth is better than during the PAN years, producing a sense of optimism for the future. A third, and key factor, is the opposition’s fragmentation: the left is split between the PRD and Morena, and the right-wing PAN remains as divided as ever between Maderistas and Calderonistas. Dialogue President Michael Shifter later asked if the PRI is simply winning by default due to the opposition’s weakness, an important question to consider as new parties are created and the Mexican party ecosystem continues to evolve.

Basáñez, who directs the Judiciary Reform Program at The Fletcher School, agreed with most of the points that Fernández raised, but emphasized the post-electoral implications that corruption and insecurity might have. On the one hand, if elections help to strengthen the PRI and the economy continues to perform well as oil prices stabilize, Peña Nieto might regain popularity and legitimacy. On the other hand, even if the series of scandals have no significant effect on the electoral results, the possibility of further social discontent and institutional weakening persists.

Both speakers emphasized that these will be unique and historic elections for the country. Independent candidates are running for the first time ever and have made an important breakthrough in the local level. The governorship of Nuevo León, one of Mexico’s most powerful states, will most likely be won by Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, also known as “El Bronco”, an independent candidate described as “blunt” and “frequently vulgar” by the New York Times. Rodríguez’s peculiar style appeals to an electorate that is clearly disappointed by political parties and that is eager to bring into power rulers that aren’t tied to deeply vested interests.

The elections have also brought their fair share of political complications. Many see the recent decision by the government to suspend teacher evaluations as mere electoral strategy to woo the teachers’ unions and its supporters. Prominent civil society actors, including Dialogue member and founder of Mexicanos Primero, Claudio X. González, have vehemently criticized the measure, as it will most likely hinder the implementation of an education reform, one of Peña Nieto’s most famous campaign promises. Given the unexpected and quick announcement of the decision, it is difficult to tell whether it will affect or benefit the PRI on election day.

Equally important, the campaign has shone a light on Mexico’s unresolved problems. Marred by accusations of excessive spending and corrupt practices, parties are dramatically losing voters’ trust, and movements that support independent candidates or that encourage citizens to nullify their vote have gained momentum. At the same time, violence and insecurity show no signs of slowing down, as reflected by the more than 8 candidates that have been murdered during this campaign season alone. Regardless of the result, the Peña Nieto administration cannot afford to lose sight of these, and many other issues, if the PRI wants to retain a victory beyond the midterm elections.