The Transformation of Learning with the Use of Educational Technology

This post is also available in: Spanish

The state of education in Latin America is mixed. While there has been significant progress in terms of coverage and schooling rates, the quality of education still leaves much to be desired. The OECD’s International Programme for Student Assessment (PISA), which evaluates mathematics, science and language, placed the region in the lowest ranking of knowledge and skills among the 72 participating countries worldwide (2015).

In addition, we are in the midst of a profound technological revolution. Incredible advances in computing, the growth of artificial intelligence and the emergence of big data are transforming all facets of life and work in leaps and bounds. As a result, the skills that are required to enter the job market are different from and go beyond what is traditionally taught in schools.

What should we do to prepare the coming generations? What skills do people need to develop in order to actively participate in society and compete in the labor market? How should education be transformed, and why is technology—when used correctly—the key to this process?

This blog seeks to answer these questions in a practical way, emphasizing the importance of adopting technology to transform learning. For the purpose of our argument, we use a broad definition of educational technologies, from an e-book or videoconference, to artificial intelligence and virtual reality programs.

The blog begins by defining and describing 21st century skills and captures the major changes that education requires to prepare students. It then cites several examples where technology is playing an important role in improving learning and transforming education programs. The aim is to lend visibility to current programs and trends that are making a noticeable difference compared with traditional practices in order to serve as an inspiration and guidance to teachers, policy makers and anyone else interested in education.

21st century skills

There are several studies and organizations that have begun to examine in detail what the future of work in Latin America will look like as the digital transformation of society progresses and tasks that were previously carried out by people become automated. Organizations such as the Inter-American Development Bank and initiatives such as the Future of Work in the Global South seek to better understand the risks and opportunities that exist in this space and the kind of concrete skills that future workers will need.

In any event, there has been a general consensus on these skills for several years. Known as 21st century skills, they refer to the knowledge and abilities that children and adults increasingly need to participate in 21st century society. They are:

- Knowledge of 21st century content and themes: This skill refers to traditional and important academic content, such as mathematics, reading and science, as well as a better understanding and awareness of global environmental, civic and health issues.

- Learning and innovation skills: Skills necessary to navigate work and life environments that are increasingly complex and changing. These include critical thinking, problem solving, communications, collaboration, creativity and innovation.

- Digital skills: The skills required to adapt to new technologies and the abundance of information. According to the DQ Institute, digital skills can be divided into three categories: (i) digital citizenship, or the ability to use digital technology and media in a safe, responsible and effective manner; (ii) digital creativity, or the ability to create new content and transform ideas into reality through the use of digital tools; and (iii) digital entrepreneurship, or the ability to use digital technologies to solve global challenges or create new opportunities.

- Life and work skills: These skills are important for adapting to an ever-changing, interconnected world with less job stability, and they include flexibility, adaptability, initiative, self-direction, productivity and responsibility.

The need to transform learning and the role of technology

The traditional teaching model of education does not allow learners to develop many 21st century skills. Conceived for another era, it is based largely on memory learning, active instruction by the teacher and passive reception of knowledge from the student. In this model, students are unlikely to develop their own initiative and creativity, or learn to collaborate with others, as just a few examples.

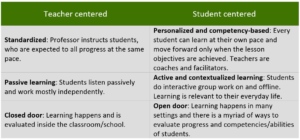

Preparing 21st century citizens requires a paradigm shift that starts with prioritizing the student, allowing them to learn at their own pace, and doing so more actively and according to their context. The table below lists some of the most prominent ideas about the kind of changes proposed to make this transformation possible.

Traditional Education vs Education of the Future

Technology for educational transformation

The use of educational technology is fundamental in this transformation mainly for three reasons. First, because technology is increasingly present in the world, and the jobs of today and the future are ever more tied to and dependent upon these tools. It is only by using technology that people can develop their digital skills. In addition, younger generations are part of the technological revolution, they have grown up with technology, including as a central component in their educational context.

Second, technology democratizes access to content and instruction by breaking down barriers such as teacher shortages, high costs or placement. In other words, it allows learning everywhere and at any time.

And third, when technology is used correctly, it promotes personalized and active educational experiences, which allow for continued learning outside of formal contexts and facilitates the development of new skills attuned to the needs of the world today and in the future.

While there are mixed results regarding technology programs in education, here we provide examples of some that have been successful in terms of scale and results and others that, while lacking rigorous evaluations, we believe exhibit some clear patterns and the potential to adopt technology successfully in programs aimed at transforming learning.

We do not see educational transformation as an option without the use of technology. Although there is always a risk of program failure, it would be hasty and erroneous to draw the conclusion that the absence of technology is a better option. In most cases, programs that use technology fail not because of the technology itself—which is a tool—but because of defects in the program’s design, implementation and development. Therefore, the fundamental question that teachers, school principals and policy makers must ask themselves is, what is the ultimate objective they are seeking, and from there start thinking about how technology can be used to support changes in teaching and improvement and transformation in learning.

Content democratization and access to cultural heritage

The state of Amazonas in Brazil launched a program known as Ensino Presencial com Mediação Tecnológica (In-person learning with technological mediation), which currently serves more than 40,000 children in 3,000 remote communities that, until recently, did not have access to primary and secondary education. Classes are taught live and virtually using video conferencing tools from a media center in the capital city of Manaus. Students attend a local classroom equipped with video and internet connection that allows them to interact directly with the remote teacher in Manaus, just as if he or she were present.

In a similar vein, some countries in the region have been experimenting with having native speakers from English-speaking countries teach languages by videoconference due to the lack of qualified local teachers, such as the Ceibal in English program in Uruguay. The initiative reaches 80,000 children in 4th, 5th and 6th grades of primary school, and more than 17,000 students in the 1st to 6th years of secondary education. To date, the program’s results have been very positive. In this model, the remote teacher does not replace the classroom teacher, but instead there is a transformation of roles. The local teacher plays an important role beyond managing class behavior, modeling how to learn, and thereby guiding students through the learning process.

Finally, technology allows access to cultural heritage, or those assets and resources that have historical, scientific, symbolic or aesthetic relevance. Globally, an important example is Google Arts and Culture, which allows anyone to access a vast global catalog of arts and culture relevant to society. Seeing some of the photographs of the works selected there, and the level of detail, is probably an experience comparable to the experiential. The Biblioteca País (Country Library) in Uruguay allows access to more than 5,000 books of literature for children, young people and adults, among which are many distinguished Latin American authors.

Customization, flexibility and learning outside of formal contexts

Technology, especially artificial intelligence, allows us to identify knowledge gaps and/or misconceptions accurately, adapts to the needs of students and can be used in and out of formal learning contexts. The Adaptive Mathematics Program in Uruguay, known as PAM, is a good example of this potential. The program, whose content is aligned to the national curriculum, offers personalized support according to the skill level of each student. PAM has been implemented since 2013 in public schools, and its use continues to increase. In 2016, half of the students between 3rd and 6th grade were using it both inside and outside the classroom. A recent evaluation demonstrated a positive effect of 0.2 standard deviations on math test scores and determined that the impact increases as students’ socioeconomic status decreases.

Mindspark in India offers another successful example: it is a learning software that adapts to the individual learning levels of students in language and mathematics. The program is administered outside the traditional school setting in computer labs. Children have 90-minute daily sessions: 45 minutes of individual computer work and 45 minutes in small groups with a tutor who instructs them. Mindspark diagnoses student misconceptions and provides individualized content to help children learn. The program has reached more than 400,000 students of all socioeconomic levels.

An assessment deployed at independent centers in low-income Indian government schools, conducted by J-PAL, found that the program had a significant impact on students at all income levels and provided more than twice as much value-added compared to a control group (+0.37 standard deviation).

Just as Mindspark and PAM help personalize student learning in math and language, technology can be very useful for improving the learning opportunities for people with special needs. Customized applications, as well as the use of virtual reality (VR), can be beneficial in shaping the learning process of people who, due to different types of disability and disadvantages (negative opinions and stereotypes, lack of physical access to learning spaces, difficulties for teachers to focus on students, etc.), have difficulty developing cognitive, behavioral, communicative and relational skills in their environment. Even where we do not find impact assessments, there are experiments that already have positive results such as Picaa in Spain, an application developed for children with autism, which showed improvement in language, mathematics, autonomy and sociability.

Betting on the benefits of technology in this field, the U.S. Department of Education announced in 2018 an investment of $2.5 million for a new program that will use virtual reality to foster social skills in students with disabilities. This is an extension of a program that since 2011 has been developing technologies for students with special needs on computers and tablets. It should be noted that part of this investment aims to evaluate the programs in order to improve their design and implementation.

100% virtual learning

A very interesting example of how technology allows learning to happen anywhere, but especially outside of traditional contexts like school, is the case of homeschooling in the United States. Today there are nearly two million students, equivalent to about four percent of the student population, who learn at home. In recent years, this population has increased thanks to the opportunities that technology has opened. Twenty-six of the fifty American states now have several models of virtual schools approved and integrated into the public system. While in some cases the learning is hybrid (i.e. the student completes lesson content online, but goes to school to do tests or different projects), in other cases it is 100% virtual.

Social-emotional skills development

Technology also facilitates learner motivation and develops self-esteem and agency through games (gamification) or interactive applications. In Chile, for example, a program called ConectaIdeas, tracks how many exercises students complete on the application and presents different types of individual and group competitions to promote student motivation. The program has been implemented since 2013 and is administered to fourth graders in public school computer labs in.

A recent evaluation of the program demonstrated positive effects on mathematical learning—0.27 standard deviation on the national standardized test. But the program also had both positive and negative non-academic results. At the same time, it managed to increase “students’ preference and motivation towards the use of technology for learning mathematics and promote the idea among students that the study effort can increase intelligence” (growth mindset). Among the less positive effects, there was an increase in mathematical anxiety and a reduction in students’ preferences towards teamwork. These results suggest that gamification may be an important tool to generate motivation, self-esteem and agency, but we must also be attentive to unintended consequences that must be considered for the design, development and continuity of these types of programs.

Foreign language

Increased motivation is not limited interactive math game programs. In foreign languages, for example, Duolingo is an example of an application that increases individual commitment to learning, while at the same time allowing democratized access to content and instruction.

Launched in 2012, Duolingo currently has 30 million monthly active users, scattered in 180 countries and learning 22 languages. Most of them are non-membership users; in fact, only 1.75% of them pay for the ad-free version. The platform is designed primarily for mobile users, and while it is used in schools (there is a version of the application designed for educational settings, which allows teachers to monitor student progress while the platform customizes exercises for each student), it is mainly used outside of classrooms.

Although there is plenty of information in newspapers about the impact of this application on language learning, academic journals only offer studies with small samples that measure specific impacts. For Duolingo, as well as other online learning platforms (such as Kahoot!), it has been observed that there is little difference in learning between those exposed to platforms and those who are not. However, there is evidence of very positive perceptions regarding the form of online learning, learner enjoyment and level of difficulty. Clearly, more research is needed.

Computational Thinking

There are several technology platforms that promote the development of digital skills. Code.org and Scratch, for example, have seen their user numbers multiply exponentially in the world, including in Latin America, and are used to teach computational thinking, a subject that has been growing in importance around the world.

Computational thinking is not synonymous with programming. According to the authors of Computational Thinking and the New Ecologies of Learning, it is a basic competency that allows you to perform better in a digital society. It is a problem-solving process that includes formulating problems that allow learners to use technology, logically organize data and analyze it, represent that data through abstractions and identify and implement corresponding solutions. Seen this way, computational thinking is not a technical skill, but a creative way to approach and solve real problems in today’s world.

Transforming Learning

The use of technology facilitates the transformation of learning processes that allow teachers to focus more on each student and support them to develop 21st century skills and abilities.

This is the case, for example, with project-based learning, where students go far beyond knowledge acquisition to developing teamwork, communication skills and initiative, among others.

How do we ensure that technology is effectively incorporated to make this transformation happen?

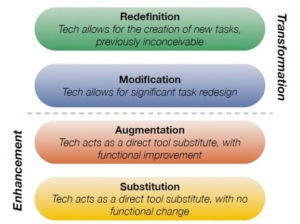

A simple way to do this is by using the SAMR framework, developed by Ruben R. Puentedura. The framework is a useful tool for evaluating how technology is used and how to take advantage of it in a meaningful way.

SAMR is an acronym that is divided into four levels: substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition. The first two levels are considered improvement experiences, where technology replaces certain tasks or functions with possible functional improvements. The latter two are seen as transformative, which means that the use of technology allows for the redesign of tasks and functions and the creation of new ones that were not previously possible. It is important to note that the framework applies to the ways in which technologies are used, not to the technologies themselves.

Substitutions and increase: improvements in education

Substitution and augmentation, the first two types of technology use in Puentedura’s framework, improve real educational practice. For example, replacing a textbook with an e-Book is a classic example of substitution. If an e-Book can download content from the internet in a way that allows students to choose or supplement their assignments with different materials, there is an improvement. The same is true with teachers using free Khan Academy videos, which can complement lessons in various subjects.

In Latin America, the current use of educational technologies corresponds mainly in the category of improvements, as we saw for example with programs like Ceibal in English and Ensino Presencial in Manaus.

Modification and redefinition: the experience of educational transformation

But what happens when technology is used to transform traditional learning and better prepare children? Can teachers, for example, use technology to redesign traditional tasks and create new ones that were previously not possible or conceivable? In the modification and redefinition categories that Puentedura defines, technology is not used simply to modify or improve an existing task, but as a tool that enables educational transformation.

Continuing with the e-Book example, we might suppose that a school aims to develop 21st century skills related to collaboration, creativity and critical thinking. To do that, they decide to give up a portion of classroom instruction and instead ask the children to prepare lessons outside the classroom using an e-Book, which can also contain adaptive learning programs, and come to class ready to discuss what they have learned and work in groups. This is called an inverted classroom, a form of blended learning. By removing the focus on instruction, the teacher designs classroom experiences that actively engage students at the individual level and in groups. If he or she wanted to go further, the teacher could also design experiences beyond classwork, for example connecting students with others from different schools or countries, to develop projects.

The network of Innova Schools in Peru, one of the most innovative private school networks in the region, has been developing this model since its founding in 2011. With 54 schools serving 43,000 students in Peru, 70% of students’ classroom time is for group work, usually project-based, and the remaining 30% is for self-guided learning, delivered through platforms such as Kahn Academy. The role of the teacher in these schools is more that of a facilitator who guides the discussions and activities in the classroom, or a companion who watches over and gives feedback on the learning process of each student.

On the other hand, in 2014 Uruguay joined the Global Learning Network (New Pedagogies for Deep Learning), a global partnership that builds knowledge and practices to develop deep learning and transform education. Through project-based learning, student motivation is expected to increase and academic content knowledge will be tied to real-life experiences. Educational technologies are an intrinsic part of this transformative process as they allow teachers to experience their roles differently, as is the case at Innova Schools.

Conclusions

The technological revolution will continue to rapidly change society and the workforce. In order for people to take advantage of opportunities in this new world, their ability to adapt, their initiative and persistence to acquire skills and knowledge during their lives will be critical.

While the responsibility of education systems is to prepare students for this new reality, there are few examples in Latin America where this is happening. The movement towards a more student-centered, personalized education that allows learners to develop 21st century competencies and skills must become the main objective of all the actors involved, including the state, teachers and the private sector. The use of a wide variety of technologies to facilitate this transformation will be fundamental. They are a critical tool for creating opportunities to democratize access to, customize and transform the teaching and learning processes.