Peru’s Election and Beyond: What’s Next?

Peruvians want an evolution, not a revolution.

The April 10 presidential race in Peru is quickly becoming a cynic’s game: an election defined by concern over insecurity, corruption, slower economic growth, and perceived political dysfunction. Because Peru generally lacks strong political parties—some analysts argue they are, in practical terms, non-existent—most candidates instead represent personalistic coalitions, almost all jockeying to present “outsider,” “reformer,” and “pragmatist” credentials.

Peru has one of the fastest growing and most stable economies in the region. But while poverty and inequality have been dramatically reduced, the public remains deeply dissatisfied with the political elites, evident in this presidential race.

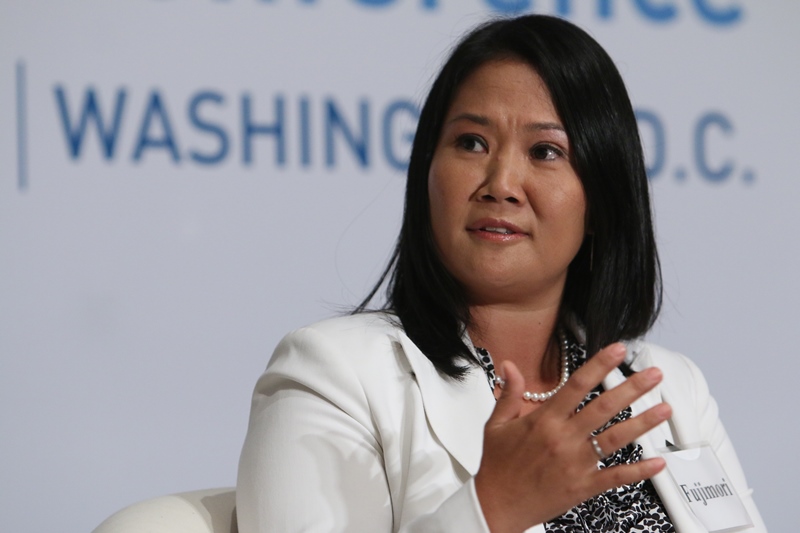

Keiko Fujimori, the frontrunner, has consistently led the polls, often with double the support of any other candidate. While economist Julio Guzmán has recently surged above the other contenders, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Cesar Acuña have also polled second place at various points. These numbers continue to change and will likely do so throughout the contest. The landscape has changed regularly as voters have shown a willingness to shift allegiances. The race so far has proved to be dynamic and unpredictable, and most predictions should be taken with a grain of salt. However, most experts believe that the vote will likely go to a run-off vote in June. Given divided support, even Fujimori is unlikely to top 50% of the vote. What happens then is anyone's guess.

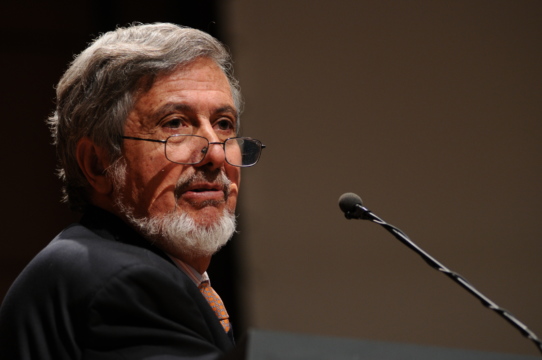

Keiko Fujimori is the candidate for the center-right party, Fuerza Popular. She is also best known as the daughter of former President Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000), who is currently imprisoned under corruption charges and for crimes against humanity committed while he was in office. Some voters worry about her support for her father’s policies and a perception of authoritarianism, both of which helped current President Ollanta Humala defeat her in the 2011 elections.

However, this election cycle Fujimori has maintained a substantial advantage. Support for her candidacy has remained over 30% in recent months, a clear lead over other candidates. Her momentum shows the enduring support in the country for “fujimorismo” and a desire to break with the current Humala administration. Many credit her father with defeating the Sendero Luminoso, a maoist-inpsired insurgenceny that engaged in terrorist and guerrilla tactics that destabilized the country in the 1980s and early 1990s, and controlling hyperinflation through austere economic policies.

[caption id="attachment_46804" align="alignleft" width="362"] Keiko Fujimori at the 2014 CAF Conference, © Rick Reinhard[/caption]

Keiko Fujimori at the 2014 CAF Conference, © Rick Reinhard[/caption]

Fujimori entered the public arena while she was still in high school when she was named first lady at 19 years old after her parents divorced in 1994. After living in the US to study at Boston and Columbia Universities, she was elected to Congress with overwhelming support.

During her failed campaign run against Humala in 2011, Fujimori’s campaign focused specifically on security and free trade. Yet she resented being labeled a ‘conservative’ since, according to her, that would fail to explain how she had the support of poor rural communities. She insisted in a 2010 interview, “to label me a ‘right-wing’ candidate is untruthful…the social programs and policies of my party are serious and will directly target the poorest sectors of the country.”

In addition, Fujimori is set to benefit from broad discontent and changing political dynamics in the country and region. Her loss in the last elections has become a substantial asset—President Humala’s approval ratings remain mired around 18 percent. Fujimori has taken advantage of this dissatisfaction and has criticized the government for not fulfilling promises, lying to the public, and for not prioritizing security. She has also capitalized on Humala’s widespread label as soft on corruption and a contrast to the policies she has proposed since her 2011 campaign. To show her commitment to anti-corruption measures, Fujimori has admitted that her father’s administration was corrupt (though she has implied that her father specifically was not) and has proposed to strengthen the Office of the Ombudsman to aggressively tackle corruption. She also vowed to not pardon her father if elected, and has considered committing to this promise in writing.

Yet Fujimori has also faced considerable criticisms. Her strong stances on security worry some, especially those already skeptical of unsavory connections to the authoritarian and kleptocratic government of her father. She has been most vocally criticized for not openly recognizing some of the atrocities that were committed under his government. Verónika Mendoza, a candidate of the left, specifically attacked Fujimori for claiming a longstanding forced sterilizations case was being ‘politicized’ in order to weaken her party. Mendoza argues that Fuerza Popular has attempted to sabotage the case investigations on several occasions. She has also been accused by several public figures, including First Lady Nadine Heredia, of an illicit use of state funds in order to pay for her education abroad.

In more general terms, she is also still a deeply polarizing figure—due largely to the legacy of her father. Supporters look back fondly on the past Fujimori era for its perceived stability and security, while critics balk at possibly electing the daughter of a dictator.

Fujimori is up against more than 10 candidates, including former presidents and presidential candidates.

Julio Guzmán (Cllaque / CC BY-SA 4.0)[/caption]

Julio Guzmán (Cllaque / CC BY-SA 4.0)[/caption]

Julio Guzmán of the Todos por el Perú party is a US-educated economist whose candidacy has seen a recent and surprising surge in support. His support has recently climbed to 20 percent, the steepest increase any of the candidates has seen during this cycle. To many, Guzmán is seen as a break from establishment politicians; his ‘outsider’ profile might lead him to garner even more support before April’s first round. Yet his campaign is also under severe scrutiny, due to irregularities in the primaries of the Todos por el Perú party, which could lead to his disqualification. According to Carlos Basombrío, it might be too early to deem Guzmán as the definite ‘outsider’ in the race as candidates like Alfredo Barnechea, a writer and journalist from the Acción Popular party, may replace him in the same manner that he surpassed other initially strong contenders. Barnechea currently polls at 3%—yet he claims to not be discouraged. If Guzmán is disqualified, Barnechea may take up the ‘outsider’ mantle.

The former governor of La Libertad department, Cesar Acuña, has also, at times, polled in second place—yet he recently declined sharply to 9 percent. The candidate for the Alianza para el Progreso party, he has tried to appeal to voters as the non-establishment candidate. Most of his supporters are from rural communities or small cities, strengthening his claim as an outsider. Even with several scandals—including vote-buying, money laundering, and plagiarism—his campaign managed to climb in the polls as many saw his private universities as a sign of being a “successful businessman.” However, the latest allegations against Acuña—that he plagiarized his doctoral thesis—not only weaken his image as a strong contender, but they have also put his campaign at risk. If true, he will be stripped of his title and—having submitted false information about his qualifications when registering as a presidential candidate—consequently could also be disqualified from the race.

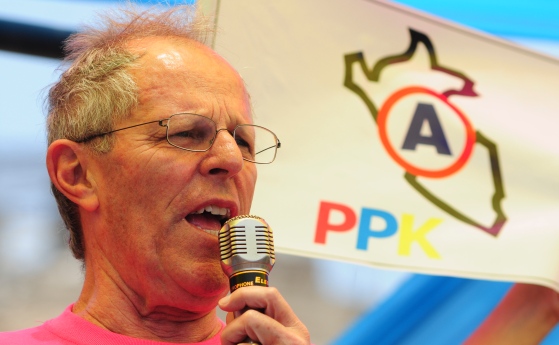

Consistently polling in second place until recently, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (also known as PPK) from the openly personalistic Peruanos por el Kambio (also PPK) party, previously served as Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, and Minister of Mining and Energy under two different administrations. A lifelong technocrat, he also ran for president in 2011 but while he surprised many with his strong showing he failed to make it to the run-off election against Humala or Fujimori. With extensive experience in economic and financial affairs, Kuczynski may have had a reasonable chance in making a run off this time around, although Guzmán poses a particular challenge for Kuczynski—both are viewed largely as technocrats. If Guzmán’s success continues Kuczynski's candidacy may be doomed.

[caption id="attachment_46810" align="alignleft" width="382"] Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (Freedomboy18 / CC BY-SA 4.0)[/caption]

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (Freedomboy18 / CC BY-SA 4.0)[/caption]

There are also two former presidents in the race: Alan García and Alejandro Toledo. Neither has performed well in the polls so far. Both are perceived as highly corrupt and often dismissed as part of the political establishment, leaving them with limited prospects for making the run-off. While the strong economic performance of García’s second administration (2006-2011) could have possibly helped him in these elections, his campaign has been hurt badly by a ‘narco-pardons’ scandal—in which he allegedly released drug traffickers in exchange for monetary payments. Toledo too is linked to scandals, and is performing even worse in the polls.

Other candidates include Verónika Mendoza from the left-wing Frente Amplio party, Hernando “Nano” Guerra García from Unión por el Perú, Daniel Urresti from Humala’s Nationalist party, and Renzo Reggiardo from Perú Patria Segura. They each have an estimated 2 percent or less in various polls, and (barring a major upset) are unlikely to see the second round.

Assuming that Keiko Fujimori makes it to the run-off election, her three most likely rivals are Guzmán, Kuczynski, and Acuña. If Fujimori succeeds in distancing herself from her father’s authoritarian government and positioning herself outside of the traditional political class, she will most likely win the second round. But surprises are almost certain to occur. Even 'frontrunner' status may become a political liability. Peruvians say they crave pragmatic proposals, particularly in dealing with economic challenges, but ‘outsider’ appeals appear to have a stronger pull among voters. By running on the security and market-friendly policies of “fujimorismo” while appealing to voters as non-traditional, Keiko Fujimori has so far gained the most traction. But she could just as easily be upstaged by a less-known and more independent candidate, such as Guzmán.

In the end, the election will likely be defined by the ability of the candidates to deflect allegations of corruption and misconduct. Simply avoiding scrutiny may be the path to victory. As Diego García Sayán explains, Peruvians do not trust any of the candidates or current politicians. The question is which candidates are able to evade negative labels—something few have managed so far.

Interestingly, while the economy is a defining factor for voters, there is relatively little difference between the various candidates (except for the left-wing Mendoza, but it seems unlikely that she will make the run-off). Even as Kuczynski and Fujimori appear to be the most market-friendly, none of the others would represent a drastic shift from the policies that have characterized Peru’s economy in recent years.

Peruvians want an evolution, not a revolution.

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

Peru’s growing urban middle class is one of the country’s greatest assets, but it also brings political and governance challenges.

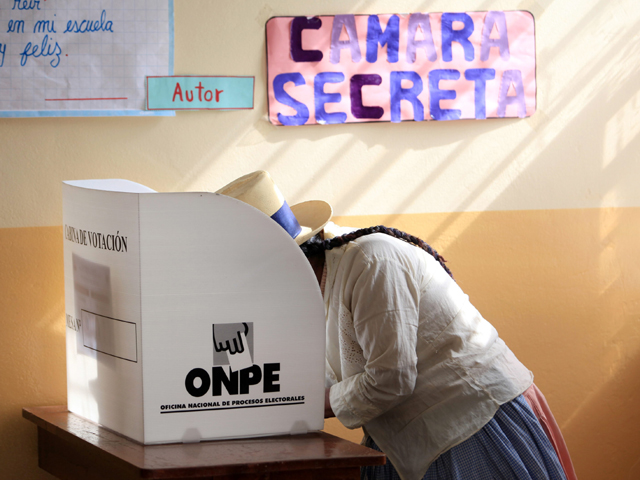

Globovision / flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0

Globovision / flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0