African Descendant Youth in Latin America University to Work: Opportunities Matter

In Latin America, African descendant youth are in the headlines in places like Brazil and Colombia. In Brazil, the federal government leads the Juventude Viva a violence prevention program to address the high homicide rates among black youth. While in Colombia, communities in Buenaventura have adopted their own “Black Lives Matter” movement which makes explicit reference to Ferguson, Missouri; highlighting the exclusion and victimization by the police confronting black youth in both cities.

However, there is other news about African descendant youth in Latin America that is not making the headlines. Although opportunities for black youth in Latin America may seem more limited due to violence and marginalization, the situation of African descendant youth is largely improving throughout the region, in part due to the high level of interest in education and greater access to educational opportunities. Despite these educational advances, however, African descendant youth still face significant hurdles as they leave universities to enter the labor market and when they interact with law enforcement.

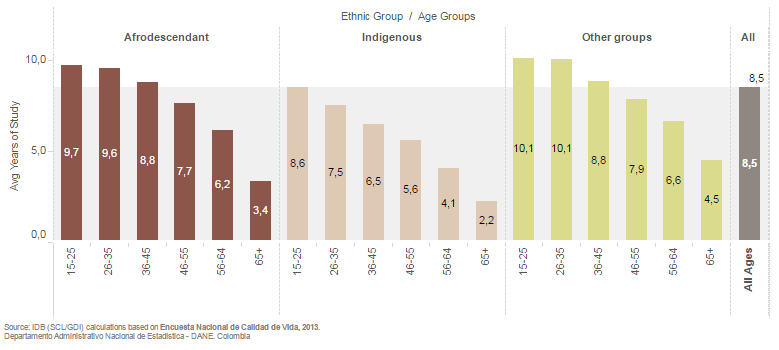

More black youth are attending colleges and universities than ever before. In Brazil the African descendant graduation rate went up 273% between 2000 and 2010. In Colombia, educational attainment gaps for blacks and whites are negligible — with both groups finishing elementary, high school, and college roughly the same rate regardless of race.

Over the last decade we have learned that access to education, particularly in Latin America, is not the same as access to quality education. However, recent public policies provide greater access for African descendant students to attend the most prestigious universities through admission incentives, such as tax breaks in the case of private universities (PROUNI Brazil), scholarship programs (Beca 18 in Peru), differentiated enrollment processes for graduates of public high schools, and racial quotas for prestigious federal universities (Brazil). For example, the highest ranked public school students in Peru are able to compete for college admission at the most prestigious universities through an interview process that enables students to demonstrate their personal abilities to achieve in a competitive academic environment.

We also see that increasingly black youth in Latin America are reaching the highest levels of education based on their own grassroots efforts. In Peru, an African descendant self-help organization Makungu para el Desarrollo, provides talented Afro-Peruvians with a peer network that encourages them to attend the most prestigious colleges and universities in Peru and abroad, while also serving as an informal support network for these young professionals as they finish university and enter the job market. Some of the Makungu students attend international graduate programs at the very best international universities and often take out private loans to enable them to attend. These returning students then serve as important role models for other Afro-Peruvian youth.

This good news on educational advancement for African descendant youth is not a recent phenomenon for black youth in Panama and Costa Rica, where college education rates have been historically higher for African descendants than for white mestizos for several decades. In Panama, 38% of African descendants have a college degree compared to 29% of the combined mestizo, white and Asian population.

Despite these important educational advances African descendant youth continue to lack equal opportunities in the labor market. Many companies only advertise positions internally, allowing only individuals that are closely affiliated to the firm through family or friends to have access to vital information about new postings or opportunities. It is still common for firms to require pictures on resumes, and to make skin color a preference for selection processes. One of the most prominent examples of racial bias, was an ad posted in 2013, for an entry level receptionist position in Lima, Peru that specifically listed light skin as a job requirement.

The role of public policy has been key to expanding labor market opportunities for African descendants. For example, an IDB-Ethos publication launched in May analyzes the levels of Afro-Brazilian representation in the top 500 firms, and finds that Afro-Brazilians are slightly over represented in private sector internship programs that receive government subsidies, with Afro-Brazilians serving as 58% of participants; however, Afro-Brazilians in positions that are only one level above this grade make up less than 36% of these lower-entry level workers. Many of the Afro-Brazilians are not retained or promoted. The situation is even more dire at the highest levels of firms, where Afro-Brazilians represent less than five percent of executives, even though they make up the slight majority, or 52%, of the national population.

The racial and ethnic gaps in unemployment are decreasing, however African descendants are still more likely to be underemployed. For example, in the case of Brazil the African descendant unemployment rate is 9.7%, compared to 9% nationally for all racial and ethnic groups and 8.2% for whites. In Peru, the African descendant unemployment rate is 5.4% compared with 4.3% nationally.

The labor market still has significant room for advancement. Promoting transparency in the labor market is a crucial to improve the competitiveness of firms by guaranteeing greater access to the entire universe of qualified candidates regardless of race. One very straight forward step is to encourage firms to post positions widely and publically – particularly entry level positions which provide the opportunity for young adults to enter the formal sector and learn more about the institutional culture.

Additionally, the public sector may consider providing differentiated labor market insertion programs for African descendant youth who may need additional training to enable them to navigate the bias that they may face when applying or interviewing for a position, and also to identify effective techniques for dealing with bias while they are working in firms. Racial and ethnic bias is a challenge in the labor market for recruitment, advancement and retention.

As policy makers design programs to address racial and ethnic gaps it is extremely important to give greater consideration to the role of unconscious bias which can limit opportunities, heighten discrimination, and cause stress to youth who face a persistent threat that they may be mistreated by law enforcement officials in positions of authority. African descendant youth are often targeted by the police and are more likely to be perceived as criminals. Recent evidence suggests that community policing techniques which bring officers closer to the citizens they serve, represent promising models to foster greater cooperation and limit the victimization of African descendant youth at the hands of law enforcement professionals. In order to better address this phenomenon in the region, it is important to encourage specific research in Latin America to enable policy makers to tailor policy interventions to best address local community concerns.

Limited labor market opportunities for African descendant youth and biased expectations by law enforcement are two factors that continue to hinder the significant progress that African descendant youth in Latin America have made in terms of educational attainment and advancement. It is vital that Latin America works to promote opportunities for African descendant youth that enable them to be productive members of their societies by providing better access to the formal labor market. African descendant youth have demonstrated that they are interested and committed to improving the economic and social lives of their nations and have prepared themselves to make a contribution – it is up to the rest of us to make sure that happens – by expanding opportunities and making the playing field more open, competitive and equitable for all.

Judith Morrison is Senior Advisor on Social Development in the Gender and Diversity Division at the Inter-American Development Bank.