Latin America Advisor

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Must Brazil Choose Between Growth & Fighting Graft?

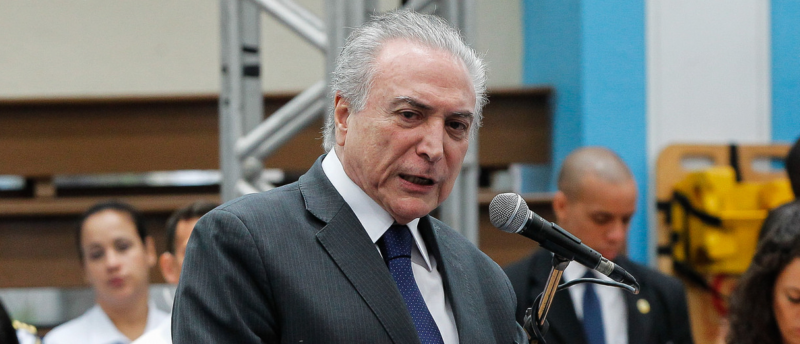

The lower house of Brazil’s Congress on Oct. 25 voted for the second time this year to spare President Michel Temer from a trial before the Supreme Court on corruption charges. Members of the leftist Workers’ Party argued that Temer should stand trial, saying the charges against him were more serious than those leveled against former President Dilma Rousseff of the Workers’ Party, who was impeached last year on accusations of violating budgetary rules. However, Temer’s allies in the lower chamber argued Temer should be allowed to serve out the rest of his term for the sake of the country’s political and economic stability. Which is more urgent for Brazil: pursuing corruption investigations—wherever they may lead—and punishing the guilty, or reviving the country’s crippled economy and reigniting stalled social progress? What bearing does Temer’s ability to sidestep a graft trial twice have on future investigations of other politicians? Should former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva be allowed to run for president next year, despite the corruption charges against him?

Peter Hakim, member of the Advisor board and president emeritus of the Inter-American Dialogue: "Brazil’s judicial authorities deserve applause for courage and high professional standards as they doggedly investigate and prosecute the pervasive corruption of the nation’s politics. Few countries anywhere have launched a more concerted attack on corruption, which in Brazil has led to the exposure and punishment of many powerful politicians and business leaders. Curbing corruption is essential for the future of democracy and the rule of law in Brazil. But Brazilian democracy is also threatened by economic stagnation and social regression. In the past three years, the economy has shrunk by 10 percent, unemployment is at record levels and chronic inequality has worsened. Confidence in government is at rock bottom. Corruption has amplified Brazil’s economic slump, but it is also true that the anti-corruption campaign could slow or even reverse a still embryonic recovery. Despite public disapproval, President Temer, a practiced and skilled politician, has made some headway in remedying Brazil’s horrendous fiscal situation. He and his economic advisors offer the only hope for congressional approval of the measures needed to accelerate growth. But Temer has been weakened by charges of corruption. Anti-corruption initiatives could also compromise the legitimacy of next year’s election. The frontrunner, former President Lula da Silva, is on the verge of being barred from running. He is awaiting the decision of his appeal of a corruption conviction, which would make him ineligible if upheld. So, what to do? Call a halt to anti-corruption efforts and allow corrupt politicians to contest elections and hold high office? Or stick with the rule of law, and potentially stall economic recovery and deny Brazilians the right to choose their president? No easy choices here. Brazilian politics are in turmoil; recovery remains precarious and political institutions have lost credibility. Now is the time to take a deep breath. Allow Temer to complete his term, which ends on Jan. 1, 2019, before pressing charges. But also, let Lula run. His exclusion from the presidential race, while Temer goes unchallenged, would dangerously politicize Brazil’s anti-corruption battle and probably diminish the judiciary’s reputation for honesty and independence."

Mark S. Langevin, director of the Brazil Initiative and research professor at the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University: "The corruption charges leveled at President Michel Temer are much more troubling than the ‘crimes of responsibility’ imagined by those leading the charge for the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. Nearly the same congressional coalition that condemned Dilma for delaying fiscal transfers to Banco do Brasil now stand in the way of holding Temer accountable for pay-to-play corruption before and during his presidential tenure. If Dilma’s impeachment was a disruption, then the lower house’s votes to protect Temer from immediate prosecution constitute a full breach of the Constitution and rule of law. The opportunistic reasoning offered by Temer’s supporters is morally bankrupt and reveals a strong movement within the Brazilian legislature to avoid accountability and evade further corruption prosecutions among its adherents. Brazil’s long-term economic and social development depends on the successful investigation and prosecution of corruption at all levels of government and throughout the private sector. Any short-term economic costs arising from removing corrupt officials from office can only be calculated against the game-changing benefits of government transparency and accountability. The votes to save Temer and the recent nomination of Fernando Segóvia (who enjoys close ties to Temer’s inner circle) to become the next director of the federal police both demonstrate the ruling coalition’s tenacity to foil the Lava Jato investigations and quash the fragile struggle against corruption. The real question is not whether former President Lula will overturn his conviction on appeal and runs for the presidency, but whether the 2018 elections will advance Brazil’s existential struggle to punch-out privilege, discrimination and corruption for generations to come. Only Brazilian voters can win that fight."

Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly and vice president of the Americas Society/Council of the Americas: "Punish corruption—or revive the economy? That’s a dangerous and false choice, but one that Michel Temer has successfully peddled to enough of Brazil’s establishment to survive in office. Temer’s message, that only he can ensure Brazil’s economic recovery continues and that structural reforms get made, has ‘paid off’—for him and his allies, anyway. The important question is whether it will benefit Brazil’s people over the medium and long term. Let’s be specific: Congress’ decision to turn a blind eye to Temer’s alleged infractions has infuriated a Brazilian public already deeply angry with the political class as a whole. It’s not just Temer who is unpopular, with his 5 percent approval rating—virtually every national politician is ‘upside-down’ in polls, with higher disapproval than approval. It is precisely this environment that explains why Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro are running first and second in polls, respectively, with 52 percent of the vote between them. Lula is benefiting from the ‘All politicians are corrupt, but only Lula did anything for me,’ narrative, which Temer’s travails have reinforced. Bolsonaro’s supporters, meanwhile, are also disgusted by corruption and are willing to overlook his other flaws (including misogynistic, anti-gay comments) in order to ‘punish’ the ruling class. Both of these candidates carry huge question marks, at best, on whether they’d govern with pro-business policies. So: By choosing to tolerate Temer’s alleged corruption, Brazil’s establishment may end up destroying the economy as well. We’ll know in less than a year."

Peter Quilter, senior fellow at The Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government: "Pursuing corruption or tackling Brazil’s political agenda is a false choice. It is no accident that the ‘forgive and forget’ argument in the name of stability is always trotted out by the perpetrators of bad deeds. In Latin America, it has been a painful leitmotif of its history of dictatorships. Amnesties, for instance, are undertaken when societies decide that political alignments of that moment can accept little else. With any luck, the amnesties are thrown out later when those alignments change. But that dry recitation masks the fact that the process is painful and wrenching, and inevitably leaves deep scars. There is little reason for Brazil as a society, in this moment, to choose to subject itself to the pain and lasting damage of letting corrupt politicians escape justice. Yes, the old guard, well represented in the Congress and party structures, stands in the way. This means Brazilian society stands on the other side of a chasm from its current political class. This will change, but it will take time. By remaining a candidate, Lula is exploiting in a most unseemly way the distortions inherent in that chasm. He should step aside, for the good of his country and its challenges. Brazil’s booming stock market conceals an underlying fragility of its inward-looking economy, unsustainable pension system and deep need for regulatory reforms. And while a credible centrist candidate has not yet cracked the top of the polls for the upcoming election, Brazilians should not fall into the trap of believing that only corrupt politicians can tackle this agenda."

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.