Rising Brazil: The Choices Of A New Global Power

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

This post is also available in: Español

Over the past few years, Latin America has seen a surge in corruption scandals, as well as massive and successful anti-corruption movements. This wave is arguably unprecedented in its scale; in the swiftness of the institutional response in some countries; and, above all, in the emergence of large popular movements to demand accountability.

This new report from the Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program finds little evidence for the notion that the newly-found zeal against corruption in the region is due to a dramatic increase in the corruption levels, either experienced or perceived. Rather, it argues that the reactions against corruption recently seen in Latin America are empirically connected to the convergence of five phenomena:

Based on these findings, the report also offers recommendations both for policymakers and for future research on the study of corruption and anti-corruption movements in Latin America.

For more information contact Ben Raderstorf at braderstorf@thedialogue.org.

Download the full report here.

For the sake of simplicity, this report adopts a largely law-based, public sector-geared definition of corruption as the abuse of public power for private gain. Even within a reasonably simple definition of corruption, it is possible to find many types of corruption, whose differences are laden with practical consequences. Of particular relevance is the distinction between petty scale and grand scale corruption, a cleavage that largely overlaps with the distinction between “bureaucratic” and “political” corruption.[1] The former occurs at the lower levels of public administration, typically during the implementation of policies, and is the type of graft that affects citizens on a daily basis. The latter takes place at the highest levels of political authority, where legal instruments and public policies are defined.

There seems to be widespread recognition of the deleterious effects of corruption for political and economic development, as well as about the enormous complexity of its causes. Protestant traditions, national wealth levels, unitary state structures, trade openness, and democracy are among the factors that have been shown to inhibit corruption.[2] The impact of democracy is complex. Some find the longevity of democracy –rather than its mere presence—to be the key factor.[3] On the economic front, high levels of corruption have been shown to negatively impact investment and growth levels, business development, income inequality, and foreign aid effectiveness.[4] The profoundly distorting effects of bribery on decisions to allocate public spending have also been established.[5] At the aggregate level, corruption levels appear to alter negatively the composition of government expenditure, for instance by lowering public spending on education.[6] On the political front, the destructive effects of corruption (and, especially, of the perception of corruption) on the legitimacy of government institutions, support for incumbents, and levels of interpersonal trust have been repeatedly found, noticeably in Latin America.[7] The evidence is less clear, however, on the impact of corruption (and its perception) on abstract support for democracy as a government system.[8]

Let us now ground the analysis on the current Latin American context by exploring first the most simple of potential links: Is the current political effervescence with corruption in the region a function of a dramatic worsening of its actual prevalence or of the popular perceptions about it?

The figures on corruption victimization available for Latin American countries tell a complex story, with widely different levels of prevalence of graft and divergent trajectories in the course of the past decade. Moreover, the results from the best sources are far from congruent, partly as a result of the very different questions used. Thus, while Latinobarometro (LB) suggests that during 2011-2015 over 27% of the Latin American population had direct knowledge of a corruption act over the previous year, down from nearly 38% during 2005-2007, AmericasBarometer (AB) estimated at 19.1% the proportion of the Latin American population that paid a bribe in 2015, a very slight reduction from the 20.1% found in 2006. It should be noted that in both cases, the region-wide victimization trend detected is positive, albeit in different degrees. Among those targeted by bribes, in virtually every Latin American country –as well as region-wide—the highest levels of victimization have been reported in interactions with the police, the courts and local governments, a pattern that has remained constant over the past decade.

The important thing to notice in these figures is the lack of systematic evidence pointing towards a substantial region-wide deterioration in corruption victimization levels over the past decade. There is also scant evidence of a momentous, widespread transformation in the severity of corruption perceptions over the past decade. Thus, the evolution of Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index shows positive trends in 13 out of 18 Latin American countries between 2005 and 2014. The average for the region as a whole increased (i.e. showing less corruption) from 3.5 to 3.9. These figures stand in contrast with the less positive results detected by the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). For the latter, control of corruption has declined in 11 out of 18 countries. For most countries the changes recorded by the WGI are very small. The average result for the region barely budged during the decade – it declined by 1.3%. These findings are consistent with other strands of evidence. The proportion of the Latin American population that regards corruption as their country’s most pressing concern has been rather low in the recent past, in virtually all cases trailing other concerns, such as crime and unemployment, by large margins. More importantly, the figures do not suggest an increased concern in most countries. In fact, in 10 of 18 countries the level of concern detected in 2011-15 was lower than in 2004-06.

One note of precaution is in order. The figures reviewed above – particularly those of victimization – hardly convey the devastation that grand corruption scandals can wreak on the political system and the popular opinions about it. These scandals do not alter victimization levels and often fail to even affect the prevailing perceptions of corruption – they merely confirm those perceptions beyond doubt. In doing so, they may spark very intense indignation and, eventually, tip citizens towards action. It is here that an interesting piece of evidence becomes relevant. A vast majority of Latin Americans have long believed that paying bribes is unacceptable. Yet, while in 2006 only 1 in 4 (23.6%) citizens of the Americas claimed that paying a bribe could be justified in some circumstances, in 2014 the figure had decreased to 1 in 6 (16.4%). Even among those who paid a bribe in 2014, 2 out of 3 believed such acts were never justifiable.[9] Hence, while victimization and perception levels do not seem to have changed dramatically or uniformly, opinions about corruption appear to have hardened noticeably in the region.

A cursory analysis of recent scandals in six Latin American countries (Brazil, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Panama) allows us to identify some patterns and lessons about grand corruption in the region.

The recurrence of corruption scandals in Latin America has happened despite the fact that over the past three decades a great variety of normative measures have been introduced to prevent corruption. Though insufficient in many regards, novel legal instruments, enhanced state capacity and multiple social accountability efforts have elevated the standards of expectation regarding basic matters of public integrity and accountability. These measures include:

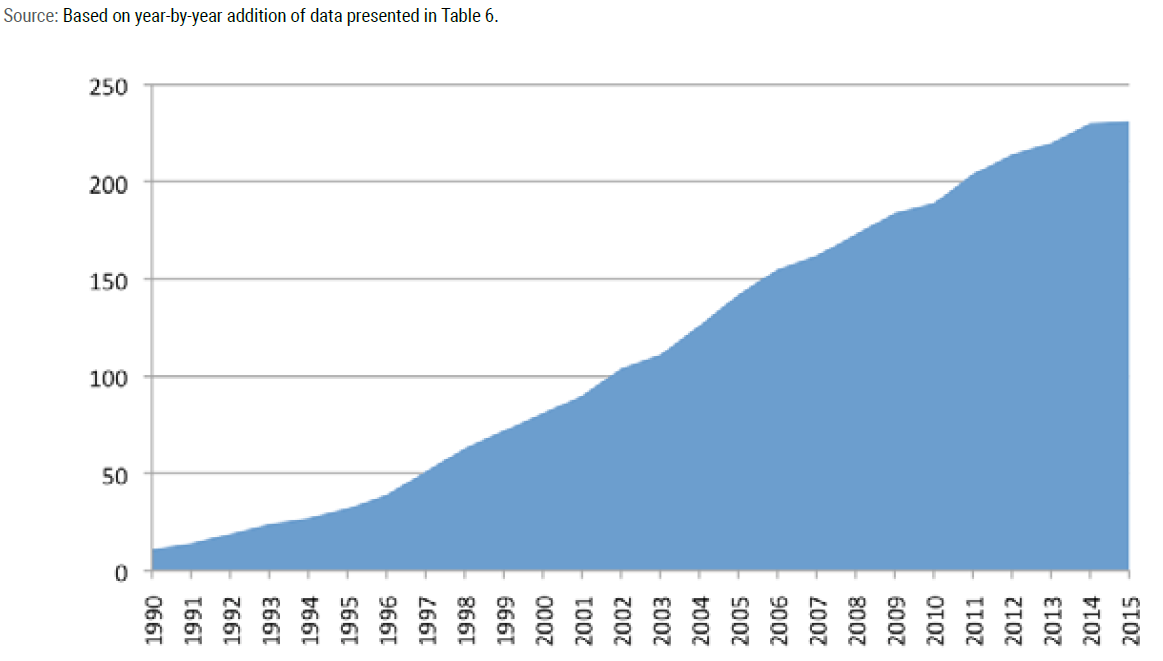

A visual illustration of these improvements can be found in Graph 1 below. This graph presents a composite, year-by-year addition of some of the most important anti-corruption measures adopted in Latin America between 1990 and 2015. The striking image of progress that can be observed here suggests that the long run effort to raise corruption on the public agenda and promote transparency initiatives has generated an unprecedented development in Latin America.

It is easier to understand why the Latin American population may be angry about corruption, than to understand why citizens are powerfully reacting against it in unprecedented ways. It is thus important to evaluate some of the hypotheses about the precipitating conditions of the region’s recent political events.

Long standing inequalities and accumulated perceptions about the essential unfairness of political systems in Latin America provide the context in which corruption occurs and is perceived by the population. Nearly three quarters of the population in Latin America views their society as unjust, and more than two thirds believe their governments are inclined to protect the interests of the privileged few, over those of the population at large. This sense of injustice exacerbates perceptions of corruption, which are pervasive across the region (72.3 on a 0-100 scale, on average). The impact of all this on the legitimacy of Latin America’s political institutions can hardly be underestimated. According to the Latinobarómetro, between 2010 and 2015, on average, only 38% of the people in Latin America were satisfied with their democracies. When combined with other factors (an economic slowdown, growing economic expectations, a citizenry increasingly empowered with information and legal resources, among others), this long-held perception can fuel a very powerful social reaction against corruption. Table 1 reveals a general correlation between perceptions of unfairness, corruption and dissatisfaction with the prevailing political regime.

This is the result of the widespread legal transformation detected in the previous section: in the vast majority of countries in the region governments have become more transparent. Over the past decade, according to the World Economic Forum, the ability of businesses to obtain information about changes in government policies and regulations affecting their activities improved in 12 out of 18 Latin American countries, as well as in the region as a whole. Budget openness, in turn, increased in 11 out of 15 Latin American countries for which there is information throughout the 2006-15 decade, as per the Open Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Index. These figures suggest that available information about what transpires in the region’s public sectors has significantly increased over the past decade. Moreover, the fact that this information is available is a reflection that citizens, journalists, prosecutors and judges are endowed with more legal resources than ever before, and are effectively using them.

The past decade has seen a decline in the relevance of traditional media (television, radio and print media) and the flourishing of the web as a source of information in Latin America. The growth of the web as an information source is concomitant to, and in many ways driven by, the rapid dissemination of social media in the region, especially amongst the middle-class and the youth. By 2015, on average, 41% of the population had a Facebook account, a figure that was already above 50% in seven countries of the region. Youtube and Google+ were already accessed regularly by over one fourth of the Latin American population. These new channels have: (i) enabled the circulation of information that would have not made it to the public domain otherwise; (ii) allowed for the rapid socialization of a narrative of discontent, often constructed around corruption and unfairness, which may mobilize large numbers of people; (iii) lowered dramatically the transaction costs to organize demonstrations; (iv) allowed for the articulation of social movements even in the absence of visible leaders. Over 90% of participants of the large anti-government demonstrations in Rio de Janeiro in June 2013 received their information from social media, particularly Facebook, a finding that rhymes with evidence from the 2010 student protests in Chile.[10] There is a strong likelihood that the new information sources that Latin American societies are increasingly tapping into have had a visible effect in shaping the recent anti-corruption activism in the region.

According to data from the Inter-American Development Bank, the proportion of the Latin American population living in households with daily per capita income in the $10-50 range, increased from 24% of the region’s population in 2005 to over 38% in 2013.[11] However, the connection of these changes to good governance and clean government has been more stated than demonstrated. Loaiza, Rigolini & Llorente (2012) found that, controlling for increases in GDP per capita, an expansion of the middle class indeed has a significant impact on the increase of public health and education outlays as a share of GDP, on the quality of democracy and on the reduction of corruption levels. The causal mechanism between income level and tolerance of corruption remains unclear. It is hard to discern from the evidence distinctive normative features of middle-income groups in Latin America that may make them particularly prone to demand clean government. Equally, the evidence that Latin American middle income groups pay proportionally more taxes and rely much more on public services is equivocal. One possible explanation concerns political participation - we do know that middle groups are more politically active than vulnerable and low-income groups.[12] With the expansion of the middle class there will be more citizens attuned with politics in general. Corruption scandals, particularly in the context of an economic downturn, simply provide a trigger for that expanded capacity for demand articulation and social mobilization to manifest itself. However, the latter interpretation must be taken with caution.

The reactions against graft that we are witnessing in Latin America are taking place in the context of a region-wide economic downturn. The average rate of GDP growth for the region as a whole has fallen from 3.7% in 2005-09 (which includes the recession year of 2009), to 2.9% in 2010-12 and a paltry 1.2% in 2013-15.[13] The available evidence suggests a glaring and growing gap between collective expectations and actual economic performance throughout the region, a gap that enables combustible social reactions against incumbents. According to data from Latinobarometro, the average approval rate of incumbent presidents in the region has fallen from 56% in 2010 to 47% in 2015; conversely, average disapproval grew from 37% to 46%. As Zechmeister & Zizumbo-Colunga (2013) have shown, “there is a strong reason to believe that individuals are more punitive of perceived corruption under bad economic times.”[14] Latin Americans are generally angry with incumbents and the corruption scandals uncovered are providing a very powerful narrative to channel and mobilize that anger.

Attributing the recent events in Latin America to the presence of unprecedented levels of corruption in the region is possible but, in the light of the available evidence, almost certainly wrong. We posit that it is more likely that behind the recent explosion of anti-corruption activism in Latin America lies the combination of a number of converging factors: the widespread perception of political and economic unfairness; the patient accumulation of pro-transparency legal reforms; the emergence of social media as an alternative source of information and an efficient tool for social mobilization; and, possibly, albeit less clearly, the rapid expansion of politically active middle income groups. Some of these factors are only now coming of age. In the context of growing anger towards incumbents, all these factors have combined to expose gross acts of malfeasance and unleash a strong social reaction against them. Almost certainly, none of the factors analyzed in this report would be able to trigger on its own the remarkable events witnessed in the past two years. Rather, it is the convergence of these elements that has unleashed a forceful social and political reaction against corruption in Latin America.

Very important things are happening in Latin America that make the region less hospitable to those that abuse public trust for private gain. Much more can and should be done to better understand, prevent and punish corruption in the region. Here are a few policy recommendations that stem from the previous sections, followed by another set of suggestions to strengthen the knowledge base on which to pursue these policies.

These are but general suggestions that require much more research and discussion if they are to be translated into concrete policies. A future research agenda on corruption in Latin America should include an effort to:

[1] Transparency International (2000); Andvig et al. (2000).

[2] Treisman (2000), Montinola & Jackman (2002), Shen & Williamson (2005), Ades & Di Tella (2000).

[3] Treisman (2000).

[4] Ades & Di Tella (2000), Kaufmann (2005), Seligson (2002).

[5] Rose-Ackerman (1999).

[6] Mauro (1998).

[7] Seligson (2002) and (2006), Canache & Allison (2008), Morris & Klesner (2010).

[8] Canache & Allison (2008).

[9] Zechmeister (2014).

[10] Magrani & Valente (2013); Valenzuela, Arriagada & Sherman (2012).

[11] Authors’ own calculation based on IADB (2016).

[12] Ferreira et al. (2013), pp. 169-170; Zechmeister, Sellers & Seligson (2012), p. 76; Weeks (2014).

[13] Authors’ own calculation based on CEPAL (2016).

[14] Zechmeister & Zizumbo-Colunga (2013), p. 1208.

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

President Lula da Silva triumphantly announced that he and his Turkish counterpart had persuaded Iran to shift a major part of its uranium enrichment program overseas—an objective that had previously eluded the US and other world powers. Washington, however, was not applauding.

The question remains if Mexico has achieved a degree of institutional development consistent with its participation in those organizations.