Will Default Dampen China-Argentina Ties?

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.

This post is an edited excerpt from “China’s Covid-19 Diplomacy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Motivations and Methods,” an August 2021 report authored by Asia and Latin America Program Director Margaret Myers, and jointly published by the Florida International University Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy and the Inter-America Dialogue.

“Wolf warrior” diplomacy, a term derived from a top-grossing Chinese film franchise of the same name, refers to an aggressive style of diplomacy adopted by Chinese officials in recent years. Sharp-edged messaging from Chinese diplomats featured prominently in China’s global communications in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, with examples evident across Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) —usually generated and circulated by Chinese embassies in the region.

To better understand the nature and extent of China’s Covid-related messaging in LAC—including of the “wolf warrior” variety—we examined over 11,000 messages posted by Chinese embassy Twitter accounts amid the pandemic.[i] We found that from February 2020 to March 2021, approximately 1,635 Chinese embassy posts directly referenced Covid-19 and that these Covid-related posts generally fell into five broad categories:

(1) PPE delivery announcements

(2) Vaccine-specific commentary

(3) Tweets conveying positive messages about China’s engagement with the region amid the pandemic, such as noting China’s commitment to cooperation with LAC, Beijing’s effective response to the pandemic, or China’s dedication to addressing the region’s pandemic-related challenges

(4) “Wolf warrior”-type messaging, strongly countering criticism of China or expressing critical views of the United States or other nations’ pandemic responses and outreach.

(5) Other Covid-19 related announcements and messages, including statistics about China’s outbreaks

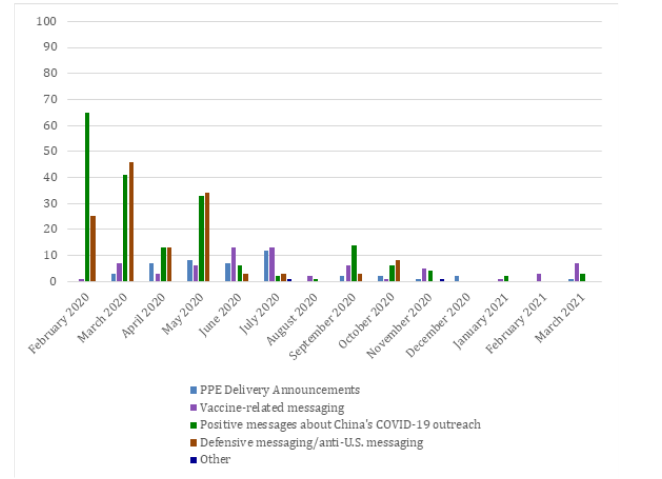

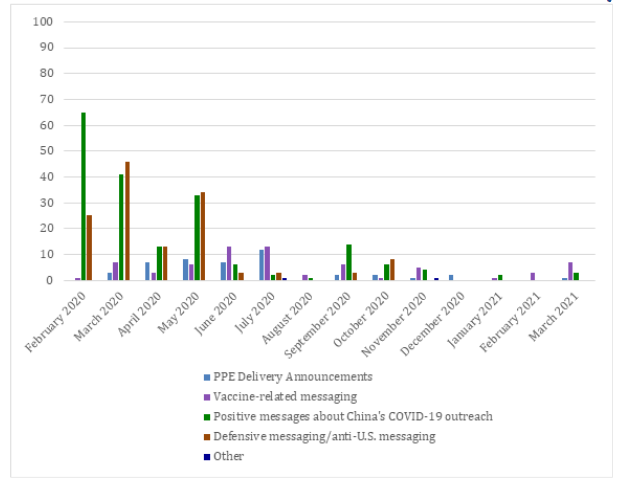

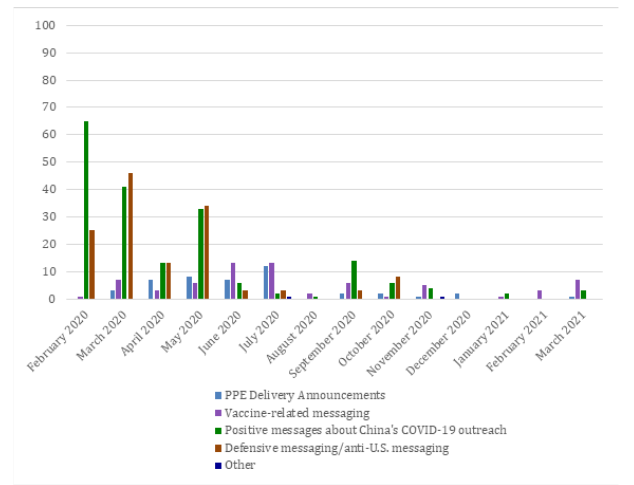

To identify possible trends in pandemic-era tweets by at least some Chinese embassies, we examined the frequency and timing of the above messaging types in three LAC nations—Brazil, Ecuador, and Grenada.

We found that:

• Promotional tweets from the Chinese embassies in these three countries (Brazil, Ecuador, and Grenada) far exceeded negative or defensive ones, or those that condemned other countries’ practices. But spikes in negative and assertive messaging were nevertheless evident in all three cases.

• Negative tweets were generally posted in response to international criticisms of China or as a reaction to claims made by public figures in LAC nations, for example. They also occasionally followed strongly worded, official statements by high-ranking Chinese diplomats or officials about China’s Covid-19 response, with diplomats echoing Beijing’s key points in their host countries. Chinese diplomats’ most combative rhetoric was also evident at a moment in time (spring-summer 2020) when China’s so-called “wolf warrior” diplomats were reportedly given some leeway to defend China aggressively and even propagate conspiracy theories through media platforms.

Of the three countries studied—Brazil, Ecuador, and Grenada—“wolf warrior”-type messaging appeared most frequently in Brazil. There, spikes in hard-hitting posts, as evident in March 2020 (see Figure 1), mostly followed critical comments made by Brazilian public officials. For example, when Eduardo Bolsonaro, Brazilian federal deputy and son of President Jair Bolsonaro, blamed China and its model of government for the pandemic in a March tweet, the Chinese embassy in Brasilia took to Twitter to suggest the younger Bolsonaro had contracted a “mental virus” during a trip to the United States.

The increase in defensive messaging in May 2020 corresponded with a speech by Wang Yi that noted China’s commitment to addressing the pandemic while also referencing U.S. efforts to politicize Covid-19. The embassy tweeted strongly worded snippets from Wang’s address. That month, the Chinese Embassy in Brazil also published op-eds defending China against allegations that Covid-19 originated in a lab in Wuhan and that China was not transparent when handling its domestic outbreak.

Positive and promotional tweets from the Chinese embassy in Ecuador far exceeded negative ones, but spikes in negative and defensive tweets were nevertheless evident in May and June 2020 (see Figure 2). Nearly every day in May and June, Ecuador’s diplomats addressed what they labeled false claims about China’s handling of Covid-19, using the hashtag #LaVerdad. They addressed rumors about Chinese people eating bats, allegations that Wuhan ophthalmologist Li Wenliang had denounced China’s actions and was arrested, reports that China was reopening its wet markets, and claims that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the source of the virus. Other messaging in May focused on defending the World Health Organization (WHO), following U.S. doubts about its political neutrality. China’s embassy in Ecuador tweeted, “In the face of the virus, those who harass and blackmail the WHO lack a minimum human spirit, and will be rejected by the international community.”

A defensive December 2020 post from the Chinese Embassy in Ecuador regarded an official communiqué issued by Ecuador’s Ministry of Foreign Relations and Human Mobility. The communiqué strongly refuted a Global Times claim that the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan may have resulted from cold food chain deliveries from Ecuador and other countries. The Chinese Embassy responded with its own communiqué and tweeted the following: “#IMPORTANT | We publish our Official Communiqué on the traceability of Covid-19; since, only scientific research will demonstrate the transmission route of the coronavirus to prevent future risks and ensure global health.”

• In all three countries, China’s Twitter-based condemnations were accompanied by a proportionate increase in positive messaging, with China evidently seeking to balance its more assertive outreach with positive information on Chinese cooperation.

• Efforts to (sometimes forcefully) defend China on Twitter were also evident in other parts of the region. Even in Peru, where bilateral relations are generally strong, Chinese diplomats traded barbs with Mario Vargas Llosa after the Nobel Prize-winning writer published a critical op-ed in El País. In the article, Vargas Llosa suggested the coronavirus had originated in China and noted that a free and democratic society would have handled the crisis differently. The Chinese Embassy in Lima responded on the Chinese social media platform WeChat, reducing Vargas Llosa’s analysis to a “smear” campaign, which, according to the post, reflected “a lack of understanding and serious prejudice against China.” The author’s books were also reportedly removed from major Chinese e-book platforms.

• In other cases, China and allies in LAC have endorsed each other’s critiques of third parties. For example, through English-language media outlets and Twitter, Chinese media and Cuban officials blamed U.S. sanctions for delays in shipments of Chinese supplies to Havana.

• Embassies’ defensive tweets also varied in tone, suggesting that the embassies and ambassadors were afforded a degree of flexibility when delivering messages. The embassy and ambassador collectively issued fewer critical tweets in Grenada, but the embassy’s tone was nevertheless harsher than in Brazil and Ecuador. The Chinese Embassy of Grenada’s defensive messaging in March was mostly aimed at refuting claims of mistreatment of African migrants in Guangzhou (see Figure 3), but diplomats also labeled former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo a politician committed to “slandering diplomacy,” quoting MOFA spokesperson and emblematic wolf warrior Zhao Lijian’s remarks about U.S. efforts to lift restrictions on official contact with Taiwan.

Ambassador to Grenada Zhao Yongchan’s tweets also used particularly strong language. They read as far more critical than Ambassador Yang Wanming’s in Brazil, for example, de-spite the prevalence of derogatory statements about China in Brazil, often coming from Jair Bolsonaro himself. Ambassador Zhao noted, for instance, that “[t]he West is containing China, awakening China’s memory of enslaving China by imperialists for 100 yrs,” and, in September 2020, that China defeated the pandemic in three months, but the United States was not able to do so after nine. In Ecuador, by contrast, Ambassador Chen Guoyou refrained from tweeting, though Ecuador embassy tweets frequently referenced his public commentary.

• China’s more aggressive posts had tapered off by summer 2020, lending some credence to Bates Gill’s summer 2020 claim that China’s diplomats were reined in as the party under-stood it had overreached with many audiences around the world.[ii] More recently, in a June 2021 speech to the Politburo study session, Xi signaled a possible throttling of wolf warrior-type outbursts, calling on the country’s leaders to engender a “trustworthy, lovable, and respectable” image for China. Xinhua later suggested that the country adopt a “humble” approach in relations with the outside world. The party may very well have noted, as a Yale University study did, that the aggressive messaging associated with wolf warrior diplomacy was not as effective as promotional messaging in moving public opinion on China.

• Whether China’s wolf warrior diplomacy persists in LAC or not, Chinese embassies in the region would now appear committed to delivering a message of solidarity, multilateralism, and cooperation, referencing China’s commitment to Covid-19 collaboration.

[i] Some of China’s embassies already had a presence on Twitter at the onset of the pandemic. Others, including those in Argentina, the Bahamas, Cuba, and Peru set up new Twitter accounts in the early months of the outbreak to communicate key messages directly to local publics.

[ii] Bates Gill, “China’s Global Influence: Post-COVID Prospects for Soft Power,” The Washington Quarterly, Summer 2020.

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.

Who in China is advising on energy engagement with Latin America?

Will protesters succeed in halting the canal’s construction?