Mexican vs Chinese Factories

With the rising cost of wages in China, manufacturers are increasingly considering Mexico an attractive location to ‘re-shore’ production.

Mexico’s Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard noted last month that Mexico and China will possibly strengthen their “strategic partnership” in 2021, probably implying greater bilateral cooperation within the context of the two countries’ existing “comprehensive strategic partnership” (“全面战略伙伴关系”), whether on vaccine provision, infrastructure development, or in any number of other areas.

But, assuming China confirms Ebrard’s comments, this announcement could also suggest a possible upgrade for Mexico in China’s hierarchy of diplomatic partnerships, perhaps reflecting China’s more energetic engagement with Mexico under the Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration.

China has demonstrated considerable interest in Mexican infrastructure projects in just the past two years, with particular attention paid to two of the main features of López Obrador’s infrastructure plan—the Dos Bocas refinery and the Tren Maya. China announced a $600 million investment in the former in January 2020 and China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) is working as a part of an international consortium to build a section of the latter. China’s State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) also recently purchased Mexico’s largest independent renewable energy company, Zuma Energía, as part of an apparent, broader interest among Chinese power companies in expanding their presence in Latin American hydropower and renewable energy.

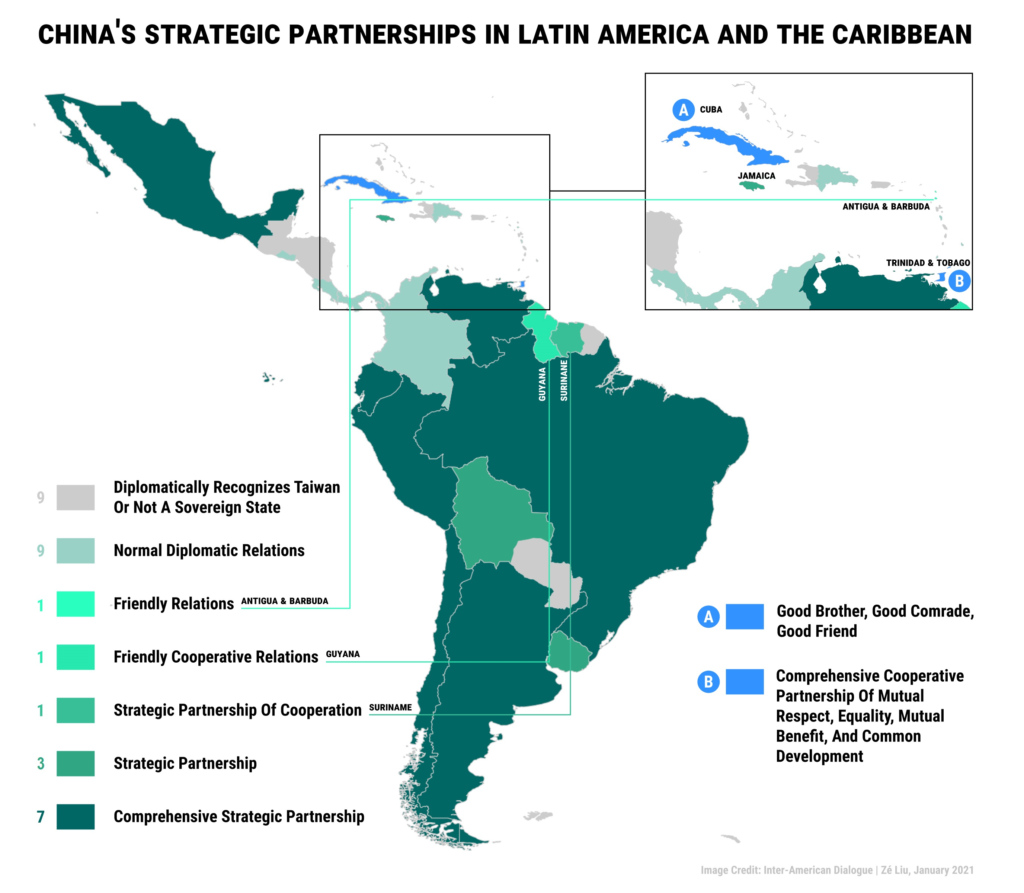

At present, though, Mexico is already among the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) that have comprehensive strategic partnerships—the highest classification yet applied to Latin American and Caribbean nations by China’s Foreign Ministry. Six other countries, all in South America, have received the same rank. They are Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. Brazil’s stands out from the rest as the first-ever “strategic partnership” to be established by China, back in November 1993, followed by Ukraine in 1995.

Bolivia and Uruguay assume a slightly lower position in China’s rankings, as “strategic partners” (“战略伙伴”) and China’s relations with Guyana and Antigua & Barbuda are labeled “friendly cooperative” (“友好合作”) relations and “friendly” (“友好”) relations, respectively. Most of Central America and the rest of the Caribbean (excluding those countries that recognize Taiwan) are simply listed on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site as having established diplomatic relations with China.

At least three LAC countries have special designations not shared by any other country in the world. The first is Cuba, which is frequently described as “good brother, good comrade, good friend” (“好兄弟、好同志、好朋友”), reflecting the historical and political basis for the China-Cuba bilateral dynamic. Trinidad & Tobago maintains a “comprehensive cooperative partnership of mutual respect, equality, mutual benefit, and common development” (“相互尊重、平等互利、共同发展的全面合作伙伴”) relationship with China, which evolved from a “mutually beneficial development friendly cooperative” (“互利发展的友好合作关系”) relationship. Although Jamaica also enjoyed the unique designation of “friendly partnership for common development” (“ 共同发展的友好伙伴关”)in the past, the two countries established a strategic partnership (“战略伙伴关系”) in 2019, bringing the China-Jamaica relationship in line with China’s global system of strategic partnerships. Suriname’s “strategic partnership of cooperation” (“ 战略合作伙伴关系”) is shared only by South Korea and Bangladesh.

What these relationships mean in practice isn’t entirely clear. Because official documentation does little to clarify their significance, most analyses of China’s diplomatic classifications refer to comments made by then-Premier Wen Jiabao during a 2004 speech in Brussels. There Wen suggested that the term “comprehensive” refers to cooperation in the economic, technological, cultural, and political fields. He also noted that a “comprehensive” relationship is both bilateral and multilateral in nature, meaning that countries with this designation may work together with China in dealing with multilateral issues. A “comprehensive” relationship is also multilayered, including both government-to-government cooperation and people-to-people diplomacy, Wen said.

The term “strategic,” as Quan Li and Min Ye (2019) describe it, based on Wen’s remarks, means “cooperation between the two countries not only has an overall importance to the bilateral relationship but also is stable and long-term, overcoming the differences in ideology and political systems.” And “partnership,” according to Wen, implies the two countries cooperate on the basis of mutual respect, mutual trust, and equality.

More broadly, China’s partnership system is thought to reflect Beijing’s historical rejection of security-based alliances. As Avery Goldstein (2005) noted, China has focused on “building stable relations without targeting any third party.” Strüver (2017) explained that China’s partnerships stand “in stark contrast to ‘threat-driven’ forms of alignment such as military alliances.” The result is a much broader and more flexible system of partnerships that, according to Strüver, prioritizes the establishment and maintenance of ongoing relations, and not necessarily the achievement of immediate and tangible results or rule-based cooperation.

Indeed, there is little clarity on how and even whether these frameworks are operationalized. Are partnerships a precondition to establishing high-level bilateral commissions of the sort that China and Brazil maintain? Does a certain level of partnership imply more direct communication between armed forces? Does development cooperation imply that China will provide a degree of development assistance? Does a partnership upgrade lead to enhanced economic or political activity or is it the result of stronger ties?

Assuming Premier Wen’s description still applies, a country such as Mexico, that has a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with China would be expected to cooperate in a range of fields and at both the bilateral and multilateral levels, casting aside ideological or political differences to achieve shared goals. This is indeed happening to some degree, as China supports certain elements of the Mexican government’s development plans. But the Mexico-China relationship has also had its share of ups and downs—including the Dragon Mart and Querétaro Railway controversies—since the “comprehensive strategic partnership” was forged in 2013.

It’s hard to imagine that moving Mexico to a next-level strategic partnership, or else assigning Mexico its own label, along the lines of Cuba’s or Trinidad & Tobago’s, would considerably alter the trajectory of the bilateral relationship. The two sides are already working together more extensively, labels aside. At the same time, diverse factors, such as longstanding China-Mexico export competition and Mexico’s much more extensive—if sometimes strained—political and economic ties to the US, will presumably preclude major shifts in the bilateral relationship.

But China’s diplomatic hierarchy is still an important signaling tool. In Mexico, an upgrade to the China-Mexico relationship would be interpreted as a purposeful, if nebulous, gesture, highlighting China’s interest in enhanced engagement. Any upgrade to Mexico’s diplomatic status would also be a clear signal to the US that China is committed to strengthening its ties in the region, even with the US’s closest partners.

See the below list from Quan Li and Min Ye (2019) noting the range of partnership terminology used by China internationally:

|

伙伴关系名称 |

Partnership title |

|

全面战略协作伙伴关系 |

Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination |

|

全天候战略合作伙伴关系 |

All-weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership |

|

全方位战略伙伴关系 |

All-round Strategic Partnership |

|

全球全面战略伙伴关系 |

Global Comprehensive Strategic Partnership for the 21st Century |

|

全面战略合作伙伴关系 |

Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership |

|

全面战略伙伴关系 |

Comprehensive Strategic Partnership |

|

互惠战略伙伴关系 |

Mutually Beneficial Strategic Partnership |

|

创新战略伙伴关系 |

Innovative Strategic Partnership |

|

战略协作伙伴关系 |

Strategic Partnership of Coordination |

|

战略合作伙伴关系 |

Strategic Cooperative Partnership |

|

战略伙伴关系 |

Strategic Partnership |

|

战略合作关系/战略性合作关系 |

Strategic Cooperation |

|

更加紧密的发展伙伴关系 |

Closer Developmental Partnership |

|

全方位友好合作伙伴关系 |

All-round Partnership of Friendship and Cooperation |

|

全面友好合作伙伴关系 |

Comprehensive Partnership of Friendship and Cooperation |

|

全方位合作伙伴关系 |

All-round Partnership of Cooperation |

|

全面合作伙伴关系 |

Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership/Comprehensive Partnership of Cooperation |

|

重要合作伙伴关系 |

Important Cooperative Partnership |

|

友好合作伙伴关系 |

Partnership of Friendship and Cooperation/Friendly and Cooperative Partnership/Friendly Cooperative Partnership |

|

共同发展的友好伙伴关系 |

Partnership of Friendship/Friendly Partnership for Common Development |

|

长期友好合作伙伴关系 |

Long-term Friendly and Cooperative partnership |

|

全面合作关系 |

Comprehensive Cooperation |

|

睦邻互信伙伴关系 |

Partnership of Good Neighborliness and Mutual Trust |

|

新型伙伴关系 |

New Partnership |

China’s Quiet Play for Latin America

With the rising cost of wages in China, manufacturers are increasingly considering Mexico an attractive location to ‘re-shore’ production.

South Korea’s entry into the TPP will promote stronger cooperation between South Korea and Latin America.

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.