China’s Energy Experts

Who in China is advising on energy engagement with Latin America?

This post is also available in: Spanish

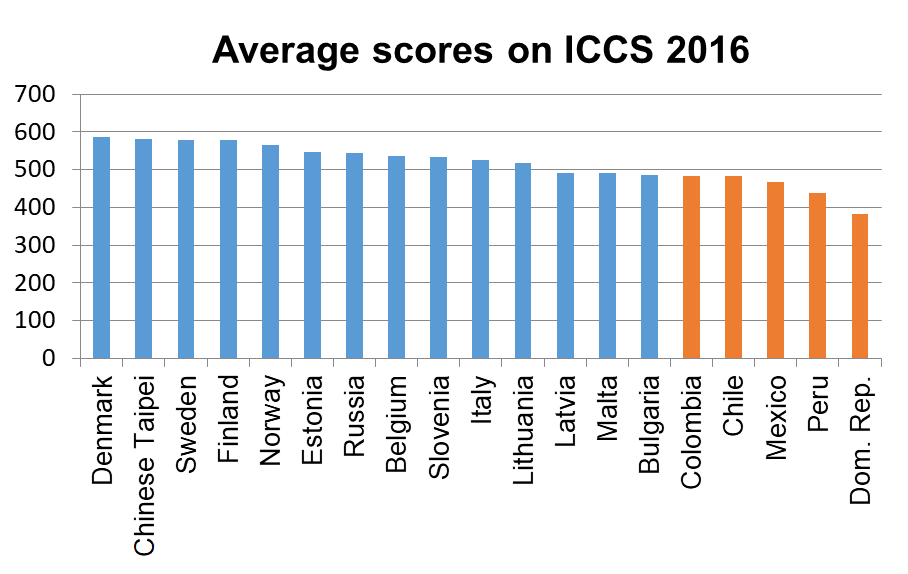

Latin American education systems may not be adequately preparing young people to undertake their roles as citizens. On April 11, 2018, the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) published the results for Latin America in the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2016, an examination that measures civic knowledge and attitudes among students around the world.

The international ICCS examination was applied to more than 94,000 high school students in 24 countries around the world to measure how well young people understand civic and citizenship concepts, how civically engaged they are, and what their attitudes are towards important issues in society. In addition to the international survey instruments, a regional questionnaire for Latin America was applied in five countries–Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Peru—that included questions relevant to the region’s political context.

Below are the main findings of the report:

1. Latin American students showed the weakest understanding of civics and citizenship topics among all students. The five participating Latin American countries took the bottom five spots for civic knowledge in the international ranking. Within the region, Chile, Mexico and Colombia had the highest levels of civic knowledge, while the Dominican Republic and Peru had the lowest. The exam, which covered topics such as national institutions, political processes, laws and policies, and democratic principles, scored students using a letter grading system where A represents the most solid understanding of civic concepts and D represents the weakest. Internationally, 35% of students scored in level A, but in the region only 12% attained this level; in fact, in the Dominican Republic, only 1% of students reached this level while 20% scored in level D. As an example, in a question that asked students to identify examples of abuse of power, 75% of all respondents answered correctly, but only 41% and 51% of Dominicans and Peruvians did so. On the upside, there were some improvements in scores in relation to 2009, the year the previous examination was administered. Mexico and Colombia, two countries that have invested in improving civic education in recent years, improved their scores by 20 and 15 scores, respectively.

2. A high proportion of Latin American students support authoritarian and corrupt practices, and the use of violence. It is worrisome that 69% of students in the region agreed that “having a dictatorship may be justified when it brings order and safety,” and 65% agreed they “it may be justified if it brings economic benefits.” The highest percentage of students agreeing with these statements come from Peru, where 77% of students said dictatorships were justified when they provided order and safety. The survey also found a worrying level of acceptance for corruption and violence. For instance, it found that 53% of students believe it is acceptable for a civil servant to help friends by giving them employment in their offices, 60% of youth believe it is acceptable to break the law when “it is not done with bad intentions,” and 58% believe people should organize to punish criminals when authorities fail to act. Levels of acceptance for these practices were higher for LAC than internationally.

3. Students in the region show high levels of acceptance of social minorities. Acceptance of different groups of people is another common element of civic and citizenship education given its importance for social cohesion. It is encouraging to see that most students are accepting of social minorities and that levels of acceptance have—for the most part—improved in the past seven years. More than four-fifths of students said they would not be bothered by having members of different social minority groups as neighbors—including people of a different race, social class, religion, region or country. In terms of acceptance for people of different races, the highest average came from Chile (93%) and the lowest came from the Dominican Republic (80%). Students also showed a growing acceptance of people of different sexual orientations, given that support for same-sex marriage jumped from 57% to 73%, on average, in Chile, Colombia and Mexico. Female students, students from urban schools, and students with higher levels of civic knowledge were the most likely to express tolerant attitudes towards minorities.

4. Civic knowledge is the strongest predictor of civic attitudes. Students with high levels of civic knowledge were much less likely than their less knowledgeable peers to agree with justifications for dictatorships, breaking the law or using extrajudicial violence., and more likely to have tolerant social attitudes. Students with more civic knowledge also reported less trust in the government and in political parties, which may suggest that having information about institutions led them to think more critically about their practices. It is interesting that civic knowledge is a stronger predictor of civic attitudes than whether or not a student came from an urban or rural background, or whether the student expected to graduate and go on to university –which indicates that civic knowledge may be as or more powerful than socioeconomic status in predicting public opinion about political issues. Furthermore – the extent to which students are taught civic topics in school (as captured in student surveys) was directly correlated to their level of civic knowledge – indicating how important it is to continue improving civic education in the region’s education systems.

5. Civic behaviors, however, are more strongly influenced by social contexts. It is interesting to note that unlike civic attitudes, civic behaviors—such as participation in politics and school activities—is not strongly correlated with civic knowledge. Instead, almost 90% of the variance in civic participation in Chile, Colombia and Mexico was found within schools, which suggests that family and contextual variables such as social networks and the media are what most influence young people’s political participation. In all, it appears that exposure to civic education both in the classroom and in other social contexts is important for raising citizens who are politically aware and civically active.

Conclusions

Civic and citizenship knowledge is essential to the development of well-rounded citizens all over the world. Given the impact of this knowledge on attitudes towards democratic principles and social minorities, it is concerning that so many youth in Latin America have a poor understanding of civic topics. Going forward, understanding the impact of different forms of civic education—both in and outside the classroom—will be important for improving our societies.

Image Credits: Rafael Gutiérrez / Flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0

Who in China is advising on energy engagement with Latin America?

Why Pakistan represents “the biggest education reform challenge” and 12 lessons that are applicable to reform efforts around the globe.

An Interview with Manuel A. Alvarez Trongé and Alejandro J. Ganimian on the quality of education in Argentina.