Corruption in Latin America: What’s next?

Corruption scandals in Latin America, it seems, are endemic and getting worse. Hardly a week goes by without some official in some country being accused of wrongdoing. Unsurprisingly, corruption is perceived as one of the main problems in thirteen countries in the region, according to the 2016 Latinobarometro survey. As The Dialogue’s Ben Raderstorf argued after the publication of the most recent Corruption Perception Index (CPI): This might not be bad news. The slump in CPI scores across Latin American countries does not necessarily mean an increase in corruption.

What is becoming increasingly evident is that the rules are changing, for the better. Judicial reforms, for example those aimed at empowering independent prosecutors, have paid off in several countries, notably Chile and Brazil. Citizens have access to more data, expanding the frontiers of public scrutiny. International standards and global practices are creating incentives to push for more stringent regulatory frameworks on transparency and anticorruption.

After the outburst of corruption cases in the last couple of years, what comes next?

First, current government structures will continue to be loosened across our region, and the world. Today, citizens are able to immediately and directly express their demands and frustrations. Incumbents, at all levels of government, are using new technologies to reach citizens in a more targeted fashion, be it to serve them better, or just to collect a larger share of votes. In any case, it is undeniable that politics dances to the waltz played by Twitter and Facebook, which prods governments to act.

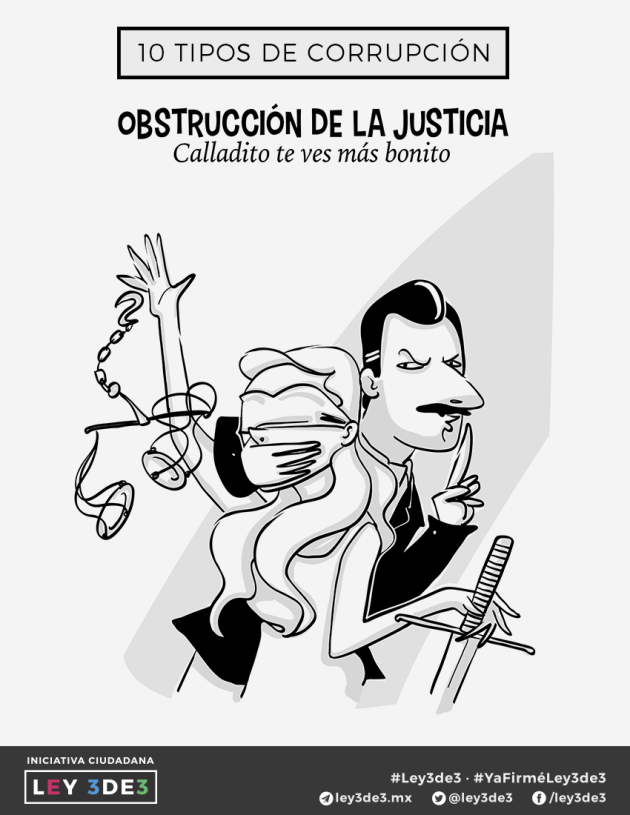

If anything characterizes social media, it is precisely its spontaneity and capacity for disruption. A good example is the 3de3 Law in Mexico, largely an initiative of civil society groups, the Plataforma Ciudadana and the Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad (IMCO) in particular. The legislation mandates civil servants to disclose their assets, conflicts of interests, and tax returns. The initiative also established a clear code of conduct for public servants, and tough punishments for corruption. It defined 10 types of corruption, including obstruction of justice, the use of confidential information, and nepotism.

The most interesting feature of this case is how quickly and effectively civil society mobilization translated into a full-scale draft law. Thanks to social media, more than six hundred thousand Mexican citizens signed the 3de3 initiative in less than three months. This spurred the introduction, discussion, and approval of the General Law of Administrative Responsibilities by the Mexican Congress by June 2016. It was included in the first package of reforms that will eventually make up the National Anti-Corruption System.

Second, the reactions of the ruling elites to these disruptions will influence outcomes. Not all governments have the political will and the necessary institutional framework to navigate the storm of changes that will accompany the transparency wave. Politicians will presumably fall into one of three groups in how they respond: those that will ride the wave and use it to promote policies that improve government services; those who will try to dodge accountability, finding shelter in the private sector; and, thirdly, those who will try to stop or subvert transparency.

For the first group, those who try to ride the wave, Uruguay is a case study in how to link transparency and better services delivery, while placing the citizen at the center of the decision-making process. The government plans to digitalize all transactional services by 2019, from making a doctor’s appointment to filing taxes.

Third, we can expect growing attention to the institutional failures that facilitate corruption in subnational governments. The focus will shift to cities. A public opinion survey carried out by the IDB in five Latin American cities – Megacities and infrastructure in Latin America: what its people think – looked at citizen perception on a range of issues, from infrastructure to the standards of public services. It showed people put citizen security and transparency as top priorities. Municipalities such as Quito in Ecuador and Bahía Blanca in Argentina are doubling down in favor of data openness, and have created websites to disclose more public information.

The final trend is that corruption will continue to be seen as one of the main barriers to better opportunities and public services. We expect citizens will broaden their definition of corruption to encompass, for example, evading taxes, which is seen as illegal but not necessarily corrupt. In other words, citizens of our region link corruption with low quality and limited access to public services, not just with blatant acts such as paying and receiving bribes. So governments need to make public services more accessible, better and more transparent. This will go a long way to convince a skeptical public that corruption is coming under control.

Juan Cruz Vieyra (@jcruzvieyra) is a specialist in the Institutional Capacity of the State Division at the Inter-American Development Bank. Alejandro Barón (@abarongg) is a consultant in the Institutional Capacity of the State Division at the Inter-American Development Bank.