Chinese Reactions to the Brazil Protests

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

This post is also available in: Portuguese (Brazil)

Seven years after Rio de Janeiro was chosen as the first South American city to host the Olympics with what the International Olympics Committee’s (IOC) president praised as a flawless bid, Brazil readies itself to bring the Games to the continent in less than a month amid political turmoil, a Zika virus epidemic, and an economic crisis with no end in sight. At the same time, the recent arrest of 12 Brazilians who pledged allegiance to ISIS has raised concern about the threat of a major terror attack during the Games. Though the threat of terrorism, especially in the aftermath of attacks across Europe, has caused alarm in Brazil, growing crime on the streets of Rio has emerged as the top concern during the Olympics, raising questions about whether Brazil is adequately prepared for the largest security operation in its history.

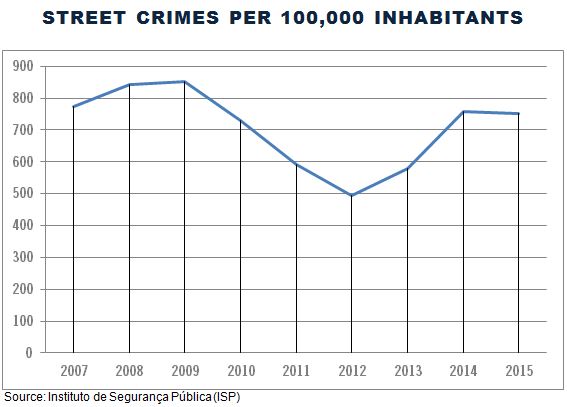

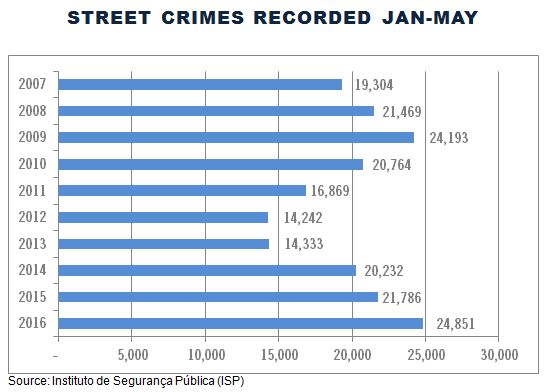

When the IOC evaluated Rio de Janeiro’s bid in 2008-2009, crime in the city was its top concern, giving the Rio bid its lowest categorical score on safety and security. Although the city has seen a steady decline in its homicide rate since it submitted its bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics, dropping by about half from 37.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in 2007 to 18.5 in 2015, street crime has been on the rise and appears to be growing as the Games approach, despite promises for increased security.

The Instituto de Segurança Pública (ISP) classifies street crime as robbery of pedestrians, robbery on public transportation, and robbery of mobile phones. The city saw a sharp decline from 53,586 recorded incidents in 2009 to 31,496 in 2012; however, that number has risen to 48,737 in 2015 and is expected to be greater in 2016. Between January and May 2016, the ISP recorded 24,851 incidents of street crime – about 7 robberies per hour – the largest number recorded in the same period since the city submitted its bid. Homicides in Rio have also increased by 10% since the beginning of the year. The Rio state security secretary, José Beltrame, said in an interview, “Without any doubt, the situation got worse in the last four months.”

This new wave of crime in Rio threatens locals, tourists, and athletes alike. One of Brazil’s most successful soccer players, Rivaldo Ferreira, publicly warned foreigners, “I advise everyone with plans to visit Brazil for the Olympics in Rio – to stay home. You’ll be putting your life at risk here.” In May, three members of the Spanish Olympic sailing team were robbed at gunpoint, handing over their cellphones to five young men on their way to breakfast. Less than a month later, two members of the Australian Paralympic team were also robbed at gunpoint, losing their bicycles at a bus stop. Both incidents took place in Rio’s wealthy neighborhoods during broad daylight. Following the attacks, the Australian Olympic Committee demanded that authorities “put extra police and security on the ground now.”

Rio de Janeiro’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, apologized after the incident, and acknowledged that “the city of Rio is a city with problems.” Paes’ comments came a week after the governor of Rio de Janeiro declared a state of public calamity, appealing to the federal government for financial assistance to prevent a “total collapse in public security, health, education, transport and environmental management.” Although Paes insists that the city of Rio is in good shape financially, state budget cuts have compromised efforts to improve security. Rio’s mayor has blamed the state government over the policing of crime, saying “This is the most serious issue in Rio and the state is doing a terrible, horrible job. It’s completely failing at its work of policing and taking care of people.”

Brazil’s Ministry of Justice announced that the Olympic Games will depend on a collaboration of both public and private security personnel: 41% public and 59% private. The government plans to deploy 85,000 security personnel, more than twice the security contingent for the 2012 London Olympics. The security force of 47,000 police officers and 38,000 members of the armed forces will be responsible for competition facilities, training grounds, and the Olympic Villages, which correspond to 860,000 people or 82% of the Games. In addition to Brazilian personnel, 250 police officers from 55 countries will support security operations.

Although Paes insists that the city of Rio is in good shape financially, state budget cuts have compromised efforts to improve security.

Brazilian police and firefighters, however, have organized protests and demonstrations across the city of Rio over unpaid salaries and a lack of basic necessities. A banner held at a protest in Rio’s international airport read “Welcome to Hell. Police and firefighters don’t get paid, whoever comes to Rio de Janeiro will not be safe.” Hundreds of agents with Brazil’s National Force have threatened to quit over poor accommodation and working conditions. The federal government has stepped in by transferring 2.9 billion reais ($850 million) in emergency funds to the state of Rio de Janeiro to help pay for security and infrastructure.

While Rio de Janeiro’s “police pacification unit” (UPP) has been praised for its success in dramatically lowering homicide rates, the pacification program has generated as much criticism as praise. With Rio likely to be the most militarized Games on record, human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have called attention to alarming rates of violence by security forces, warning that increased security could also lead to an increase in violence. Though the program is expected to continue beyond the Olympics through at least 2018, in order to foster lasting peace and prosperity in Rio, security efforts must adequately address the underlying causes of violence in the city, poverty and inequality, instead of merely containing violence in its marginalized favelas.

Despite these challenges, it is likely that Rio will host the 2016 Olympic Games successfully and without any major security incidents, just as it did the 2014 World Cup and Pope Francis’ visit. The city, however, will continue to be plagued by its security problems well beyond the Games. As Mayor Paes said, “The Games offered [Rio] an opportunity to look at our troubles and work to make us a better city,” adding that “security is not an Olympic problem, public security has been a problem in Rio for as long as one can remember. It is a problem for all of us, always.” Though the Olympic Games could have been a catalyst for lasting change in Rio, it has failed on many of its promises, more so for Brazilians than those who will visit for just a few weeks.

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

An analysis of the current state of education in Brazil – what does the report find and what does that mean for Brazil?

Interview discusses Latin America and its recognition of the role of education in the economy and democratic governance.