What Is Driving Peru’s Relationship with China?

What is the state of Peru-China commercial ties today?

Chinese firms and banks have expressed interest in numerous transport infrastructure projects in Central and South America over the past two years, many of them traversing the region and/or linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Among the largest are proposed transoceanic rail routes, which, if built, will run from Peru’s Pacific coast to the Brazilian Atlantic. Considerable financial support for these railways has been promised by China, but few project details have been disclosed, leading to speculation on the project’s design, feasibility, and social and environmental consequences.

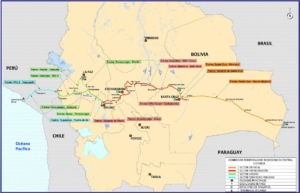

China has supported at least two general railway routes from the Peruvian Pacific to the Brazilian Atlantic. The first of these—the “northern route”— would measure about 5,000km, stretching from a still undetermined port on Peru’s Pacific coast to the Santos port in Brazil.

A second possible route—the “Corredor Ferrovario Bioceanico Central” or “Twin Ocean Railway”—would run not only through Peru and Brazil, but also through Bolivia, attempting a more direct East-West trajectory.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang indicated broad support for the “northern” route during their respective trips to Latin America in 2014 and 2015. A bilateral agreement was signed with Brazil during Xi’s visit allowing China to invest in Brazil’s railways. Li Keqiang organized groups of Chinese, Brazilian, and Peruvian experts to assess project feasibility while in the region. At the APEC Summit in Beijing in November 2014, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Peru’s Ministry of Transport and Communication and Brazil’s Ministry of Transport to create a trilateral working group on railway development.

The “central,” Bolivia option has attracted far more attention in recent months as a result of Bolivia’s extensive diplomatic efforts. According to a party responsible for negotiating Chinese interests in the rail project, Bolivia pleaded its case for inclusion in the project during a meeting with Chinese officials in December 2014. Over the past two years, the country’s Ministerio de Obras Políticas Servicios y Vivienda (MOPSV) has also worked, with Inter-American Development Bank support, to complete and present preliminary studies of project design to Chinese, Peruvian, and Brazilian officials and potential investors. Bolivia will make its case yet again during a meeting of the Peru-Bolivia Bi-national Cabinet in Puno, Peru on June 23.

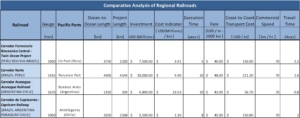

The Bolivia route is appealing to investors for a variety of reasons. It is not only shorter (around 3,755.5km, according to MOPSV’s study) but would require significantly less construction—much of the rail needed to cross Bolivia has already been built. Bolivian rail is relatively easily connected to Peruvian and Brazilian rail, moreover, according to analysis by COSIPLAN, UNASUR’s council for infrastructure planning. And plans to link Bolivia and Argentina are a plus for investors looking to access Argentina’s major agricultural producing regions.

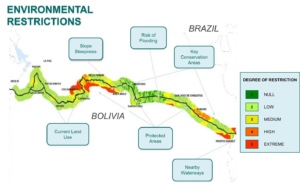

Unlike the northern route, the Bolivia-inclusive route also avoids passage through the especially biodiverse Isconahua Reserve, Vale do Rio Juruá, and relatively untouched forests in Brazil’s Mato Grosso, Rondônia, and Acre states.

Ilo, a port in the south of Peru, is the most likely candidate for the Peru-Bolivia-Brazil route’s Pacific terminus, although other Peruvian ports, such as Matarani, Lomas, Abierto, Grau, and Mollendo, have been proposed. Assuming selection of Ilo, Bolivian rail would link to Hito IV, Peru and would connect to existing Brazilian rail near Puerto Suarez, Bolivia.

In addition to China, German authorities have also reportedly signaled their interest in the Peru-Bolivia-Brazil route in January 2016, focusing on opportunities for provision of safety signaling technology and rail construction. If an agreement is reached, German firms such as Deutsche Bahn and Siemens, could work with Chinese companies on railroad construction. The government of France and rail companies such as Škoda have also resportedly expressed some interest in the project.

Chinese finance for the Bolivia route, to the extent it materializes, would probably come from China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange through the “Special Loan Program for China-LAC Infrastructure Projects,” announced in 2015 and administered by CDB. It might also come from an already approved China Export-Import Bank US$7.5 billion credit line to the Morales government. Signed in 2015, the credit line will be distributed on a project by project basis. Proposed projects include a stadium, airport development, and other transport infrastructure projects, but could also include portions of “central” railway. The Bolivia portion will cost approximately US$7 billion, according to a 2016 MOPSV study.

Though still largely in the planning phase, the project has generated concern among environmentalists and human rights groups in Latin America and elsewhere, as well as in communities expected to be affected by the rail project. Many have argued that proposed routes will damage the Amazonian ecosystem and negatively affect vulnerable indigenous communities. The “central” route is thought to be less environmentally damaging than the “northern” one, but Bolivia’s own study outlines several parts of the proposed route that will encounter environmental challenges or run through conservation sites.

The technical challenges associated with this mega-project are numerous. Technical requirements differ across countries, for example. Special brake technology is necessary in some parts of Bolivia due to steep inclines. Brazilian and Peruvian landscapes have their own unique demands.

Political developments might also affect the project’s trajectory. New administrations in Brazil and Peru could deprioritize the project, for example. Progress on a feasibility study in Brazil was already slowed by recent political turmoil.

Railway planning, whether for the “northern” or “central” routes, will also face growing scrutiny from NGOs and other groups as plans progress. In Bolivia, a recent scandal alleged that Chinese company CAMC Engineering was granted special privileges from the Bolivian government, having obtained nearly $500 million in mostly no-bid state contracts. Deal-making with Chinese companies will be closely monitored by Bolivian and other NGOs, labor unions, and environmental groups in the coming months.

Whether China can accomplish the sort of regional infrastructure integration so often supported by Latin American leaders, regional organizations, and multilateral development banks still remains to be seen. Several attempts to connect the Atlantic and Pacific in South America have of course preceded China-supported plans. All encountered unexpected delays and technical challenges. The “InterOceanica” transcontinental highway, proposed in early 2006, was expected to reduce trading costs between Brazil to Asia by US$ 100 per ton. But major sections of the highway, which extends from Peru through the Andes and the Amazon to Brazil’s Pacific coast, are either unfinished or degraded. According to Jorge Barata, who heads the Peruvian offices of Odebrecht, the Brazilian construction firm that built many of the newest stretches of the road and holds a 25-year concession to maintain them. In a February 2014 New York Times article he indicated that “[t]he cost of river transport ends up being a lot more competitive.”

If it does proceed, it is unclear whether the Peru-Bolivia-Brazil project can indeed be finished by 2024, as projected in IIRSA analysis. That’s an ambitious timeline considering the current pace of other projects in Brazil, especially. China, Peru, and Brazil are already delayed in the completion of feasibility studies for the “northern” route. Their report was expected by May 2016. Talks among involved parties are ongoing, however, and China remains clearly committed to connecting the region by means of these and other transport infrastructure projects. We should expect some progress in the coming months, and news on the various routes by November’s APEC meeting at the latest.

Silvana Serra is a researcher for the Dialogue’s China and Latin America program.

What is the state of Peru-China commercial ties today?

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

Chinese lending to Latin America and the Caribbean hit an all-time high of $37 billion in 2010.