Puerto Rico: A Delicate Path to Solutions

As the “island of enchantment” descends further into a nightmarish debt and economic crisis, fights for Puerto Rico’s future have spread to Washington and the public eye.

The territory today owes over $70 billion to creditors, a debt that Governor Alejandro García Padilla has called “unpayable.” Since early 2015, the Puerto Rican government has implemented severe austerity measures and delayed outstanding tax refunds in order to service some of the debt. These measures have largely been insufficient and unsustainable. On May 1st, the Puerto Rican government defaulted on most of a $422 million payment related to the Government Development Bank (GDB), worrying creditors, lawmakers, and Puerto Ricans alike.

For years, Puerto Rico has been trapped in an economic death spiral of stagnation and inefficiency.

And it may have to do so again on the biggest payment yet—$2 billion in bonds—on July 1st, barring swift Congressional action. Political intransigence has not only delayed solutions. It has also been a distraction from the structural problems revealed by the debt crisis.

The origins of the ballooning debt load are complicated. For years, Puerto Rico has been trapped in an economic death spiral of stagnation and inefficiency. In 2006, congressionally-mandated tax breaks intended to spur manufacturing on the island expired and businesses fled. With jobs and workers leaving, the government borrowed money through municipal bonds to counter a sclerotic economy and prevent cuts to the public sector. Much of that borrowing was enabled by shortsighted federal tax incentives that inflated bond yields, making Puerto Rican debt more attractive than it should have been. Other antiquated and inane regulations—including a longstanding scheme where much of the island receives its electricity for free, driving public utilities deep into debt—have since exacerbated the situation.

Behind this crisis, conditions on the island continue to barrel towards a deep social crisis. With 45% of the population living in poverty, decaying educational and healthcare systems, a 12.2% unemployment rate, and a looming Zika epidemic (the CDC predicts a quarter of the island’s population will contract the virus within a year), the severity of the situation is difficult to overstate.

Outmigration is a particularly worrying long-term repercussion. As US citizens, Puerto Ricans are free to live and work anywhere on the mainland. Thousands of skilled workers are understandably choosing to do so. However, their departure may hinder economic growth on the island for the next decade and beyond. Outmigration also means the population left behind grows ever older, causing further strains on the already depleted pension system.

Political fights for Puerto Rico’s future

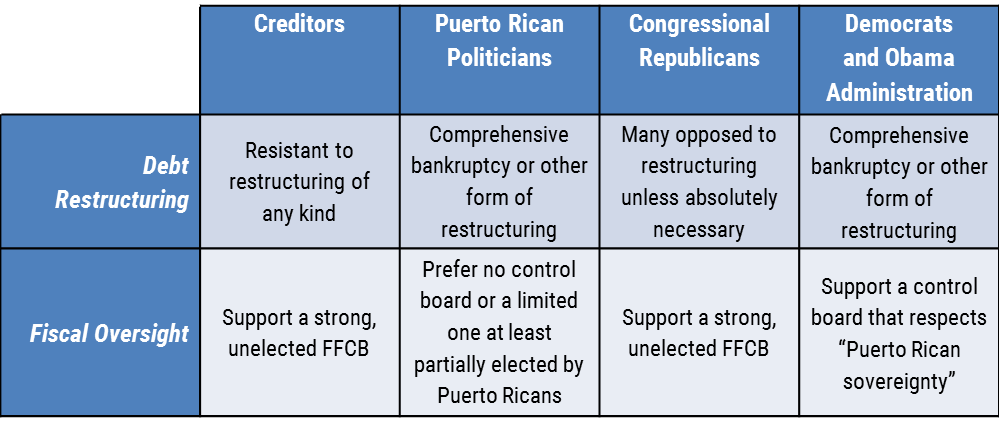

Politicians in San Juan and Washington continue to disagree on what a rescue bill should look like. Stark ideological divisions over debt restructuring and a financial control board continue to impede progress.

Underneath these divisions are decades-old tensions over Puerto Rico’s political status—statehood, status quo, or independence—fraught relationships between San Juan and Washington, and questions of responsibility and blame for the current crisis.

Debt restructuring

Investors and some members of the US Congress staunchly oppose debt restructuring. For the former, restructuring could mean direct losses. For the latter, a debt haircut would be “a bailout” and a dangerous precedent for future cases—including state and municipal governments around the country. By any account though, relief of some kind will likely be necessary. The initiatives taken by the local government have proven insufficient for it to comply with future payments in almost any scenario; the alternative to restructuring is likely default.

However, as a territory, Puerto Rico has no access to the federal bankruptcy system, leaving municipalities (including public utilities) with unpayable debts and no direct legal recourse. Island politicians attempted to force the issue in 2014, drafting their own law to allow its public utilities to restructure their debt obligations themselves (the “ley de quiebra criolla”). Creditors sued in response, arguing it was unconstitutional, as Chapter 9 of the Federal Bankruptcy Code specifies that no state is allowed to draft its own bankruptcy laws. The question, however, hinges on whether or not Puerto Rico counts as “a state” in that specific sense. The case is now before the Supreme Court. Those who support debt restructuring hope it will overturn lower court decisions in favor of creditors and pave the way for restructuring. Otherwise, they argue, the island will be caught in legal limbo: not enough “a state” to access Chapter 9 and too much of one to draft its own laws.

On the issue of debt restructuring in particular, the consequences of non-action are far greater than the imperfections of compromise.

Still, even if the Supreme Court rejects the appeal, some debt restructuring may be possible. The latest draft of the PROMESA bill, a proposed Congressional intervention, would allow some mechanisms typically used in bankruptcy processes without granting bankruptcy. The measure, however, faces criticism from both sides. Creditors fear it will force losses on them by cutting their debt and halting lawsuits. On the other side, many House Democrats, the Treasury Department, and Puerto Rican politicians support more comprehensive debt relief—many arguing for full bankruptcy. For their part, many Republicans condemn offering bankruptcy protections under Chapter 9, arguing that it would undermine rule of law, unfairly burden tax payers by offering a “bailout” for irresponsible fiscal policies, and damage the island’s access to capital markets—thus risking future economic growth.

Between these various demands, room for compromise and consensus is slim. On the issue of debt restructuring in particular, the consequences of non-action are far greater than the imperfections of compromise. Creditors may need to accept some restructuring as unavoidable; House Republicans should follow Speaker Paul Ryan in seeking pragmatic instead of punitive restructuring solutions (restructuring, after all, is in no terms a federal bailout—it is similar to processes open to any municipality on the mainland); and Democrats and Puerto Rican politicians should do the same in ensuring bondholders are not left out to dry. After all, hedge funds and other financial firms are not the only creditors. Around a third of the island’s total debt is owned by everyday Puerto Ricans.

Fiscal oversight

In the longer term, parties are also negotiating how to constrain spending going forward and prevent future crises. Fiscal oversight is likely inescapable, considering widespread mistrust towards the island’s politicians and their apparently inability to resolve the crisis. Past mismanagement and lack of transparency are much to blame for today’s troubles. Many in Washington advocate for strong fiscal oversight in the form of a federal financial control board (FFCB)—a board of seven members appointed by the Obama administration and one non-voting member, García Padilla, that would oversee and approve the island’s finances. The board would determine which debts would be restructured (if any), audit the territory’s books, and balance the budget by force whenever the local government is unable to do so. House and Senate Republicans see the strong control board as crucial to the territory’s recovery.

The Obama administration, however, is less aggressive on fiscal oversight. The Treasury initially proposed a plan that, along with total debt restructuring, included fiscal oversight that “respects the island’s autonomy”—although how that differs in practice is less than clear. Governor García Padilla has already stated his disappointment with the FFCB proposed by the House, above all because Puerto Ricans would have no voice in electing its members. The governor has worked on creating a united front in opposition to the bill among local politicians, hoping to gain a stronger negotiating hand with Congress. House Democrats also oppose an imposed FFCB, with Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi calling the Republican-proposed board “undemocratic.”

In all likelihood, fiscal oversight will be the most delicate and difficult part of any compromise. Many House Republicans are so skeptical of the Puerto Rican government’s ability to balance its own books that anything short of a strong FFCB is a non-starter. However, such a board may not be well-received by Puerto Ricans—many of whom perceive it as a colonial imposition and fear that such a “super board” would be quick to make sharp cuts in services and jobs. In this area too, both sides must be ready to compromise. So long as Puerto Rico’s political status is unchanged, the island must accept some degree of fiscal coercion from Washington. And Congress must also recognize the need for Puerto Rican inclusion in the process, preferably through some degree of representation on a FFCB.

Beyond the debt crisis

However, even if a compromise bill of some form is produced, Puerto Rico’s problems will not go away. The crisis’ underlying causes remain. The local government faces continuous structural problems including tax evasion, complex and perpetually imbalanced budgets, incoherent long-term fiscal planning, lack of transparency, and monopolistic public service structures. Puerto Rico needs ambitious plans to restart and sustain economic growth, including investment in infrastructure, education, and specialized industries such as tourism. All of these can only be effectively addressed by a FFCB working in cooperation with Puerto Rican voters and politicians. Without a fiscal and political consensus on the island, the board is likely to face constant political friction, discontent, and reactionary policymaking. The 2016 elections on the island may also further hinder solutions, especially if García Padilla is succeeded by an opponent to the plan channeling voter anger at Washington. Long term solutions will require a political consensus that is sorely lacking.

Much of the current crisis stems from distortions and inconsistencies resulting from Puerto Rico’s territorial status. That relationship must be clarified.

Moreover, policymakers in Washington should not forget that Puerto Rico’s economic future, beyond this crisis, still matters. A rescue plan could hardly be considered successful if it condemns the island to a new chaotic era of austerity and slashed public services, and as a result, continued economic stagnation, poverty, and outmigration. While the territorial government is to blame for covering up years of economic weakness and inefficiency with a glut of borrowing, also responsible are the many convoluted federal incentives and regulations (most passed by Congress) that gave Puerto Rico access to cheap lending in the first place. A punitive approach will do little to help the island pay back creditors, fix structural problems, and build a better future for Puerto Ricans.

Finally, the crisis should also encourage all parties to work towards finally resolving the island’s political questions. Much of the current crisis stems from distortions and inconsistencies resulting from Puerto Rico’s territorial status. That relationship must be clarified. In the meantime, three and a half million Americans are trapped in economic and political limbo.