Will Default Dampen China-Argentina Ties?

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.

Argentina’s presidential elections are just around the corner, with primaries scheduled for August 9 and the first round of general elections on October 25. Argentina’s next president will face a number of political and economic challenges, including ongoing negotiations with bondholders over the country’s 2002 default, inflationary pressures and power struggles among the main political actors.

Energy too will feature as a prominent issue in the new president’s agenda, with the country’s energy subsidy policies taking a toll on public finances and the government struggling to attract international investment in its burgeoning shale industry.

So, what are the key energy challenges that the incoming administration will face?

Argentina’s regulatory environment has improved since the government amended the Hydrocarbons Law in October 2014, establishing a more unified and stable regulatory system for unconventional resources, including shale, offshore, and tight oil and gas, as well as coal bed methane. However, various regulatory challenges remain. The government has yet to pass comprehensive environmental legislation for unconventional resources, and current laws lack the technical, environmental and social provisions needed to regulate an activity that differs greatly from conventional oil and gas. In addition, the law’s application is not retroactive, so the many shale concessions in some of the country’s most promising formations that national energy giant Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) and other local and international companies bought up in recent years will not be subject to the new law. More broadly, it remains to be seen how the next administration will apply the law in practice.

For years, the Argentine government has sought to cut costly energy subsidies first implemented in 2002 to protect consumers from soaring inflation following the financial crisis. But fears of public backlash have prevented the government from taking action. From 2012 to 2013, energy subsidies increased by 48%, soaring to a total of $14.9 billion in 2013, according to the Argentine Association of Budget and Public Finance and Administration (ASAP). In 2013, subsidies represented some 20% of total government expenses and 4% of GDP. Energy subsidies have also encouraged demand for oil and gas, while deterring investment, further contributing to Argentina’s heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels.

Argentina has limited local oil and gas expertise and technology, and its domestic market of goods and services suppliers for the industry remains small. The need to import oil and gas equipment leads to higher costs for companies operating in Argentina. In addition, like many other Latin American countries from Mexico to Colombia, Argentina needs to expand its pool of skilled labor and invest more in research and development in oil and gas to support the shale boom.

There has been relatively little social opposition to shale operations in Argentina so far, even as other Latin American countries face mounting conflicts over natural resources. According to recent figures, about 70% of the local population in the Neuquén Province — home to Argentina’s largest shale play, the Vaca Muerta — supports extractive operations there. Vaca Muerta is also located in a remote, sparsely populated area.

However, potential social conflicts remain a concern. The Mapuche indigenous tribe, whose population is declining, has held small-scale demonstrations to voice opposition to energy projects on their lands. More significantly, the country’s trade unions have organized widespread strikes against oil companies. In May, for example, oil workers of the “Patagonia Norte” union announced a 24-hour strike in response to the dismissal of 250 employees from international oil services companies, including Halliburton, Schlumberger, Weatherford International and Baker Hughes. The growing frequency of labor disputes has deterred some international companies from starting operations in Argentina and raised costs for companies already operating in the country. Looking ahead, residents in Buenos Aires may start to oppose shale drilling over social and environmental concerns, which could lead to an anti-fracking campaign similar to those in other parts of the world.

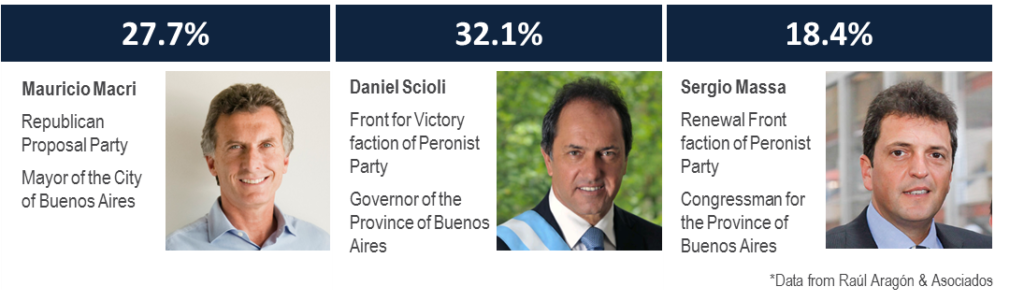

All three of the main presidential candidates – Daniel Scioli, the governor of Buenos Aires province, Mauricio Macri, Buenos Aires city mayor, and congressman Sergio Massa – have vowed to advance the country’s extractive industries, which they view as an important economic driver. While the next administration is unlikely to introduce drastic changes to hydrocarbons regulations, it will likely try to improve the current business climate in order to encourage investment.

As a member of the governing coalition, Daniel Scioli has been the least critical of current energy policies. Scioli has supported the re-nationalization of YPF, the new Hydrocarbons Law and YPF’s CEO Miguel Galuccio.

However, he has indicated that his economic development strategy, based on the three pillars of agroindustry, mining and energy, will bring important changes for the energy sector. His Argentine Development Foundation (DAR) – which brings together economists and experts from a range of fields – is currently working on proposals for sustainable exploration and development of shale reserves. During a visit to Vaca Muerta last year, Scioli said he was increasingly “passionate” about the asset and its potential to drive economic development. Furthermore, Franco La Porta, the Secretary of Public Services for the Province of Buenos Aires and one of Scioli’s principal energy advisors, has stressed the candidate’s desire to improve conditions for joint public-private investment in the sector. Scioli’s close relationship with Galuccio has helped him to gain a good understanding of the shale industry. In fact, Scioli has openly stated that, if elected, he would maintain Galuccio as YPF’s CEO.

Mauricio Macri has promised the most market-friendly policies of the three candidates, proclaiming the need for “sustainable” energy development, including reductions in subsidies and further investment. To attract foreign investors, he says the government should be more transparent in dealing with companies.

Macri is able to draw on the expertise of members of Fundación Pensar, a think tank that has developed public policies for his Propuesta Republicana (PRO) party since 2010. Fundación Pensar’s energy sector coordinator, Sebastián Scheimberg, has repeatedly emphasized the importance of eliminating energy subsidies and investing in infrastructure to remove market distortions and lower costs. Another of Macri’s consultants, former Secretary of Energy Emilio Apud, has advised the new government to look beyond hydrocarbons to renewable energy sources to increase self-sufficiency. In April, PRO members and representatives including Banco Ciudad Director Rogelio Frigerio reaffirmed the importance of eliminating costly energy subsidies. Macri has also revealed that, if elected, he would appoint the president of Shell Argentina, Juan José Aranguren – who is due to step down from his post after 37 years – to his cabinet. Aranguren, a staunch opponent of the Kirchners and their energy policies, is already collaborating with Macri’s team of advisors.

Congressman Sergio Massa, a member and founder of the Renewal Front Party, supports encouraging investment in the sector to achieve self-sufficiency and increase Argentina’s growth and development. In February 2014, Massa met with eight former energy ministers, asking them to outline Argentina’s long-term energy policy. During the meeting, Massa noted the importance of advanced planning, saying the government should look 20 years to the future when determining energy policy. He suggested creating a national agency for hydrocarbons that would audit oil resources, plan the country’s energy matrix and set parameters for environmental sustainability. In November 2014, Ricardo Delgado – the head of consulting firm Analytica and Massa’s main advisor on energy policy – argued that the energy deficit is worsening the country’s overall trade deficit. He proposed lower subsidies, a reduction in energy consumer tariffs and multiple exchange rates to curb inflation and improve the country’s overall macroeconomic environment to attract foreign investment. In April, Renewal Front member Miguel Peirano noted that Argentina’s energy resources represent a “huge economic opportunity” for the country’s future. In his opinion, an administration driven by the party would seek to generate large-scale investments, remove existing investment restrictions and curb inflation by removing the dual exchange rate.

Amid this complex web of energy sector challenges, we outline seven key policy recommendations for the next administration.

Foreign investment is impeded by Argentina’s complicated financing structures. Changes to the overall regulatory environment would help encourage foreign investment in the country’s energy sector. Policymakers should consider gradually removing barriers to the repatriation of dividends, lifting currency controls and removing import restrictions, which create unnecessary costs for oil and gas operators. Moreover, companies would benefit from increased transparency, for example through the establishment of predictable oil and gas prices.

Reducing the amount of money spent on consumer subsidies would provide substantial savings and help stimulate energy sector investment. The recent international oil price decline provides policymakers with the unique opportunity to decrease subsidies with less impact on consumers.

Argentina needs to work towards a shared vision for the energy sector, which will require the cooperation of the provincial and national governments along with the country’s powerful trade unions. Policymakers and employee organizations should work together to update and modify current practices and regulations to improve the sector’s productivity.

Encouraging the development of local suppliers would strengthen the process of re-industrialization and help the country develop import substitutions. This would in turn help reduce Argentina’s external trade balance and augment the country’s scientific, technical and human capital capacities. As a national energy company, YPF could further develop its national network of service providers. Developing local suppliers would also lower costs for the energy industry.

Argentina’s energy matrix is overwhelmingly dependent on imported fossil fuels, leaving the country exposed to international oil and gas prices, which hinders budget forecasting. Policymakers should make full use of alternative sources of energy – including renewables, such as solar, wind and nuclear energy – to expand production and establish a sustainable energy matrix. This will require support from the federal government until these sectors are better established.

The vast majority of energy projects are costly and take many years to develop. Argentina would benefit from a comprehensive, long-term national energy policy that leverages the country’s resources (particularly shale oil and gas) and sets the country on the road to self-sufficiency. As part of this long-term plan, policymakers should undertake feasibility studies and work at the local, provincial and federal levels to ensure support for key infrastructure projects.

While YPF has signed an impressive number of deals with private companies, Argentina’s energy industry would also benefit from greater transfer of knowledge and technology at the government level. Argentina’s policymakers could consider technical cooperation programs between the Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation and its counterparts in other industrialized countries, as well as increased knowledge transfer between research institutions and public universities.

Juan Cruz Díaz is managing director at Cefeidas Group.

Lisa Viscidi is director of the Energy, Climate Change & Extractive Industries Program at the Inter-American Dialogue. Follow her on Twitter @lviscidi.

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.

Column on the results of the 2007 PISA exam.

Article discusses Argentina’s ban on publishing the results of student achievement tests and its implications for education quality.