China’s Transition: Opportunities for Latin America

This post is also available in: Portuguese (Brazil)

More important than the installment of Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang as China’s new leaders is a momentous challenge that awaits them: to expand domestic markets. If they succeed in stimulating the national taste for consumption that has already begun to entice China’s 700 million urban dwellers, the effects will reverberate around the globe. Latin America’s mining, manufacturing, and agriculture sectors will encounter new challenges and opportunities as the impact of China’s consumption boom ripples concentrically outward.

Since China can no longer rely on US and European markets, its new leaders will approach nationally led growth as an imperative for maintaining employment and social stability. However, major obstacles stand in their way. Large export-oriented state enterprises enjoy access to rebates, loans, and stimulus subsidies, while small private firms face restrictive conditions for acquiring credit and employing workforces. The result is a high level of employment in the prior, which often look more like social welfare outlets than economically productive firms. By comparison, small companies that could provide higher-value adding products and services for the domestic market currently have little to offer employees. To address this problem, the new leaders will likely ramp up spending on genuine health and welfare programs, facilitate consumer credit, and support paid vacation, all of which will enable citizens to seek more productive jobs and generate disposable income.

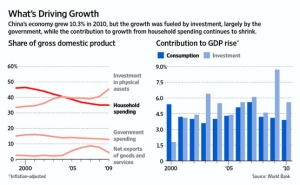

Xi and Li’s pursuit of internal markets carries serious implications for Latin American natural resource exporters. The Chinese central government projects that as private investment grows, its own levels of investment (particularly in infrastructure and heavy industry) will decline from 45% to 25% of GDP. Latin American iron ore, copper, coal, and oil exporters will therefore need to identify new Chinese customers at the provincial and county levels as construction and development become increasingly driven by private urban consumption.

On the positive side, farmers in Argentina, Brazil, and Peru will benefit as 300 million additional Chinese people leave behind rural agriculture for urban consumer culture between now and 2025. Mexico too could become an agricultural powerhouse owing to its floating exchange rate, abundance of arable land, and favourable climate.

Latin American manufacturers will also benefit from China’s emphasis on internally led growth. This sector has suffered debilitating competition from imported Chinese electronics, clothing, and other consumer goods. Having reportedly lost over 900,000 jobs to Chinese competition, Mexico in particular will welcome the trade diversion created by demand within China. Furthermore, rising wages in China (now 86% of those in Mexico, up from less than 50% a decade ago) are augmenting Latin America’s competitiveness as a destination for foreign investment.

With GDP set to grow 7% per year through to 2020, Chinese producers will need to become more familiar with their own complex and fragmented markets. Savvy foreign providers, from small marketing consultants to large financial institutions, will see opportunities here. Those operating in Latin America are already familiar with emerging markets, and therefore well placed to explore this critical niche in China’s evolving economy.

And for reference, a comparison of consumption and investment as a share of GDP growth: