Can Spain Solve the Cuba Problem?

By all accounts, Spain wants to bring change to the European Union’s Cuba policy. In so doing, it is tackling a foreign policy challenge that often sheds more heat than light.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

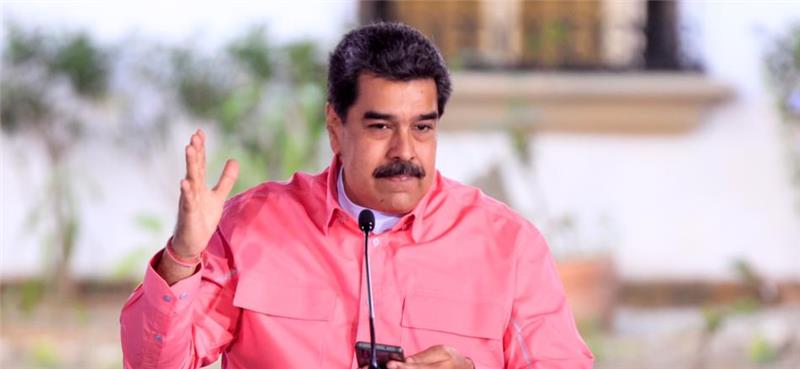

The European Union on Jan. 25 called for political talks in order for Venezuela to hold “credible, inclusive and transparent local, legislative and presidential elections.” The statement came less than two months after Venezuela’s Dec. 6 legislative elections, which have been widely denounced as fraudulent and which the main Venezuelan opposition parties boycotted. What is the likelihood of such dialogue happening this year in Venezuela? Would talks between President Nicolás Maduro’s government and the opposition lead to a productive outcome? What actions should international actors, such as the European Union and the Biden administration in the United States, as well as Maduro allies such as Russia and Iran, be taking now to help stabilize Venezuela?

Vanessa Neumann, former Juan Guaidó-appointed Venezuelan ambassador to the United Kingdom: “No one who thinks clearly believes there will be free and fair presidential elections in Venezuela in 2021. While it’s long overdue, we have neither the drivers nor the conditions. The electoral farce of Dec. 6 has strengthened Maduro’s co-option of everything, including foreign NGOs and civil society, paradoxically bringing greater stability: a stabler downward spiral into further horror, without credible challengers to disrupt that terrible momentum. The dictatorship is winning. Currently, its only motivation to sit down would be to get its sanctions lifted and live the international high life again. That won’t help the Venezuelan people. To drive a real dialogue, we need a paradigm shift. As in any negotiation, you have to develop some trust across sides but most importantly with the target audience: the Venezuelan voters. First, start with key performance indicators of positive outcomes from smaller joint projects that deliver measurable results to ease Venezuelans’ horrific suffering, through vaccination and food programs. That would establish solid credentials of delivering for the people and the confidence-building measures that support a framework for shared projects and outcomes, such as an election. While the international community supports those joint confidence-building efforts through the United Nations and other multilaterals, it should also continue to wield a stick, by punishing criminals and kleptocrats. It should treat the Maduro regime as the transnational criminal organization it is. If the dictatorship wants to improve its image (and if the opposition does, too, while we’re at it), it should earn forgiveness from the Venezuelan people by serving them. Let’s get some real political competition going to the benefit of Venezuelans. All of this, of course, is contingent upon the key international stakeholders having the policy bandwidth to deal with Venezuela while they tackle the pandemic and rebuild their economies, which remains to be seen.”

Abraham F. Lowenthal, founding director of the Inter-American Dialogue and of the Latin American Program at the Wilson Center: “Harsh sanctions to induce Nicolás Maduro to step down have failed. Thinking that the United States would use force to dislodge Maduro was a fantasy. But successful national negotiations and international diplomacy to achieve a peaceful democratic transition in Venezuela are hard to imagine in 2021. Such negotiations can only succeed when a dominant sector of the government and a largely unified opposition both recognize that neither can achieve their core objectives without genuine give and take and painful compromises. Neither side has been ready for negotiation so far except as a means of gaining tactical leverage. It is time for a new approach based on realistic expectations. The Guaidó ‘government’ controls no Venezuelan territory, no longer represents the National Assembly, has been somewhat discredited by its excessive dependence on the Trump administration and has lost considerable public support and some of its international backing. It should concentrate now on building back support by helping to improve humanitarian, human rights, public health and economic conditions while projecting a unifying, long-term vision that mobilizes support in the streets and eventually at the ballot box. Experience in many countries of peaceful transitions from authoritarian rule toward democracy show that this goal is out of reach until conditions change within both the authoritarian regime and the opposition. Meanwhile, Venezuelan democrats and their international supporters should take practical steps to improve conditions for Venezuelans. They should be ready to work with the Maduro regime on humanitarian relief, responding to Covid-19 and economic reconstruction, while maintaining their call for human rights, credible elections and democratic freedoms. The Biden administration should explore whether Cuba, China, Russia and the United States can agree on measures, each in its own interest, to help stabilize Venezuela and assist its recovery.”

David Smilde, visiting fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame and senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America: “With the opposition marginalized within Venezuela and its position weakening internationally, the Maduro government is consolidating its control over Venezuelan society. This does not sound like a promising context for negotiation, and indeed face-to-face negotiations between the opposition and the regime seem unlikely. However, there is an opportunity for the United States to engage the Maduro government directly and negotiate sanctions for democratic openings. Sanctions relief could be offered in exchange for a credible electoral council, opposition parties’ leadership restored, electoral disqualifications lifted and real international observation (not accompaniment). Such an agreement on regional elections could build momentum for further openings and electoral solutions to the crisis. The Biden administration obviously has its plate full, and Venezuela is not among its top priorities. However, it and the European Union should engage immediately regarding the possibilities for a new, balanced and credible electoral council, as the selection process has already started. They should also engage a broader swath of democratic opposition, including civil society networks that are expanding to include entrepreneurial associations, organized labor and organized religion. The United States and the European Union should also renew efforts to engage Russia, China and Cuba, each of which have strategic interests but are not committed to perpetuating the status quo. Setting aside the pressure-collapse theory of change to work for broad, inclusive agreements that recognize the interests of all stakeholders could change the game and eventually lead to a breakthrough.”

Marc Becker, professor of history at Truman State University: “One thing that we learned from Trump’s baseless claims in the November 2020 election is that it is one thing to claim that an election is fraudulent and something entirely different for significant fraud that would have altered the outcome of a vote to have actually happened. An opposition boycott intentionally designed to delegitimize an election should be seen exactly for what it is. Barriers to participation did exist in Venezuela, as they exist in all elections: the Democratic Party, for example, successfully prevented the Green Party from gaining a ballot line in Wisconsin in the U.S. presidential election. What needs to be considered is whether abuses in Venezuela are significantly different from those that happen elsewhere. By all accounts, for example, overt fraud happens much more frequently and at much higher rates in Honduras, but neither U.S. government officials nor former colonial powers in Europe blink an eye. This obviously leads to the question of why, and the answer is quite clear: conservative Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández is a loyal ally of these imperial powers while Maduro is not. If conditions were as they currently are in both countries, but Hernández was the leftist while Maduro was not, the full court press to overthrow a government would be leveled against Honduras, not Venezuela. That fact makes the blatantly hypocritical nature of this political positioning immediately apparent. The best thing that the European Union and the Biden administration can do to help stabilize Venezuela is to leave the country alone.”

Jennifer McCoy, professor of political science at Georgia State University: “There is a chance for dialogue given two new conditions: a change in government in the United States and the displacement of the Guaidó-led National Assembly with a new government-dominated National Assembly. But the obstacles are great: the old strategy of ending the usurpation as a first step (that is, removing Maduro) has clearly failed, but the opposition remains suspended. Guaidó still claims leadership but lacks an institutional position and a clear base. The Maduro government wants relief from sanctions and personal indictments, which the United States controls. Thus, the Biden administration has the opportunity to flexibilize sanctions in exchange for institutional rebuilding and allowing independent actors to receive and implement humanitarian relief. But to contemplate leaving or sharing power, Maduristas will need clear guarantees of future political life as well as spelled-out transitional justice mechanisms about how human rights abusers will be held accountable, and their supporters will want clarity on political and economic inclusion. International allies should help Venezuelans focus on coexistence rather than regime change. They could start with partial or pre-accords on the most dire needs, such as impartial mechanisms to receive and distribute Covid-related and humanitarian relief, removing the criminalization of information and organizing, and releasing political prisoners. Such pre-accords can build confidence toward a larger and longer-term political framework to rebuild institutional and social conditions needed for competitive elections, restart the economy and guarantee political and human rights for all. Such a framework might involve an internationally backed joint interim government or a jointly chosen technocratic government. Elections alone will not solve the underlying problems. Groups working toward change in Venezuela need to build new coalitions, look at longer-term strategies and consider gradual steps to address humanitarian emergency and rebuild institutions.”

Gustavo Roosen, president of IESA in Caracas: “Any negotiation in Venezuela will be an obstacle course. All recent processes have failed. The government is increasingly attached to power, and its adversaries are divided and harrassed. At the end of 2020, Venezuela’s GDP decreased by 80 percent, and poverty level stands at 90 percent. That has resulted in a humanitarian crisis of close to five million migrants. An opinion poll taken in the second half of January indicates the state of confusion of the Venezuelan population: 80 percent believe Nicolás Maduro should leave power now, 70.4 percent thinks the opposition should purge itself and unite and 77.5 percent believes that there can be no free elections at the present time. Additionally, 80.7 percent thinks that a dialogue would not work, and 78.3 percent thinks the spurious newly elected National Assembly will not solve the crisis. Also, 86 percent thinks a transitional government made up of Madurismo and the opposition forces will not be able to govern the country. What can the international community, which is afflicted by the pandemic and its ensuing economic difficulties, do in this situation? It can do relatively little. The Biden administration could negotiate the elimination of some economic sanctions in exchange for a free and independent selection of a new electoral council, a prosecutor’s office and an independent Supreme Court the first step toward holding a free election of governors and mayors this year. The next step in a negotiation would be a free and auditable presidential and legislative election before 2024.”

Diego Arria, member of the Advisor board, director of the Columbus Group in New York and former permanent representative of Venezuela to the United Nations: “It is regrettable that the European Union did not follow the European Parliament resolution recognizing Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president, knowing full well how unrealistic is to continue ‘to hold credible, inclusive and transparent local, legislative and presidential elections,’ without telling us how to achieve this unprecedented feat under a narco-militarized tyranny. After more than 20 years, the Chavista-Maduro regime has learned that the international community will only go so far as to impose sanctions on them, though ones that are strong enough to bring it down. The Europeans know what it means to deal with tyrants, but they are historically late in realizing it. The latest case was the years-long promotion of endless negotiations with the criminal Milosevic-Karadzic duo in the former Yugoslavia. Venezuela has suffered thousands of extrajudicial killings, has hundreds of political prisoners and torture victims, and five million of its people have had to flee the country. As to actions by the European Union, suspension of diplomatic relations with Maduro’s criminal corporation would be a wake-up call that would level the field for a real and credible negotiation to regain freedom. The European Union should also refuse to continue to be held hostage to member states controlled by governments with vested interests in the status-quo regarding Maduro.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

By all accounts, Spain wants to bring change to the European Union’s Cuba policy. In so doing, it is tackling a foreign policy challenge that often sheds more heat than light.

Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan president, has clearly been enticed by the Libyan drama, where his longtime friend and ally, Muammar al-Qaddafi, is under siege from rebel forces.

Estimates of the volume, composition, and characteristics of Chinese lending to the region since 2005.

File Photo: @NicolasMaduro via Twitter.

File Photo: @NicolasMaduro via Twitter.