IACHR Report on Citizen Security & Human Rights

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Colombian officials recorded 215 killings of human rights activists and social leaders last year, country’s highest rate ever, the nation’s human rights ombudsman, Carlos Camargo, said Jan. 23. Last year’s toll rose from 145 in 2021. What are the main reasons behind the escalation in killings of human rights activists and social leaders in Colombia, and why are they being targeted? How much is Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s government doing to protect rights activists, and what more should it do?

Elizabeth Dickinson, senior analyst for Colombia at International Crisis Group: “The rise in assassinations of social leaders is one of several trends in Colombia’s violence that point to an acute worsening of the conflict. Following their rapid expansion during and after the pandemic, armed and criminal groups used 2022 to cement their territorial control by subjugating and terrorizing civilian populations. These armed organizations use targeted violence, together with handouts and economic opportunities, to build a compliant base for their illicit activities. Targeting social leaders is a way to silence the community: by threatening or killing local leaders, they broadcast the potential repercussions facing for anyone who dares speak out. Other methods of intimidation include curfews and forced confinement, which reached its highest recorded level ever last year. Simultaneously, they are recruiting heavily among adolescents and children, with promises of economic support. This potent mix of carrots and sticks enables armed and criminal groups to wield control over community life, potentially entrenching them for years in rural areas. The Petro government’s total peace plan beseeches armed and criminal groups not to kill, torture or disappear in order to begin talks with the state. Though formal talks have only begun with the rebel National Liberation Army, or ELN, and legal challenges have at least temporarily limited the scope of talks with criminal organizations, the administration says its priority is to reduce the humanitarian toll of violence. The government’s enticements toward dialogue have reduced homicides in some areas, but they have not yet managed to curb the types of violence, including social leader assassinations, that armed and criminal groups consider central to their strategy for territorial control. In initial conversations with these groups, the government should pay particular heed to these types of violence to ensure that armed groups do not merely stop killing but also soften their asphyxiating hold over many communities.”

Juan F. Vargas, professor of economics at Universidad del Rosario: “Human rights activists and social leaders have long been targeted in Colombia, especially during periods when traditional rural elites see their monopoly on political power threatened by left wing newcomers—in most cases after political reforms that attempt to democratize the political arena. The cleansing of the Patriotic Union party in the 1980s and 1990s, which the Inter-American Court recently recognized as a state-led genocide, is an infamous example. The recent peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and ultimately the peace agreement that the government reached with that insurgency in 2016, which entailed mechanisms for the political participation of former combatants, intensified the targeting of activists and leaders. Former FARC strongholds have been particularly vulnerable. More recently, the victory of the first left-wing president, Gustavo Petro, in Colombia’s 200 years as an independent nation exacerbated the trend as powerful elites saw their power menaced by Petro’s campaign promises of political and economic redistribution. Unfortunately, due to its recent ascent, its conflictive relationship with the armed forces and the state’s known lack of capacity to control the entire territory, the new government hasn’t been able to improve the security of local leaders and activists. Instead, President Petro has diverged his policy priority to a naive energetic transition that will most likely carry large fiscal and political costs.”

Julia Zulver, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the University of Oxford, and Kiran Stallone, Ph.D candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley: “We are gender and conflict scholars whose work focuses on violence against social leaders in Colombia. Our research shows that armed groups see social leaders as a threat because of their public-facing work, which often involves justice-based demands, speaking out against violence, attempts to document atrocities and sometimes even directly challenging the spaces where armed groups operate. Social leaders who pursue peacebuilding and environmental agendas are at particularly high risk. Our research focuses on how women activists are targeted in distinct ways when compared to men activists. Last year, we interviewed 40 Colombian social leaders and human rights activists about the threats they receive from armed groups. Unlike their male counterparts, women leaders received threats of sexual violence and threats that challenged their position in the public space. They were told that as women, they belonged at home performing domestic duties. Male leaders, although they were killed in higher numbers, did not receive such threats. This leads us to believe that women are being targeted and punished not only for their leadership, but also for transgressing the gender norms that armed groups establish in the territories they control. We also found that many social leaders requested protection measures from Colombia’s National Protection Unit and were either declined or received nothing due to high demands and limited resources. Moreover, we found that when protection measures were provided, they did not meet leaders’ needs. Both women and men leaders told us the transportation they are assigned estranges them from their communities, and that their security details don’t adequately protect their families and children. And in the case of women leaders specifically, we learned they are assigned bulletproof vests that don’t fit their bodies. President Petro has promised to assess and reform Colombia’s national protection system, but we are not yet seeing comprehensive results. We insist that any actions to protect social leaders must take women’s and men’s different experiences into account, and must create spaces for both to voice their specific—and gendered—protection needs.”

Gwen Burnyeat, junior research fellow in anthropology at the University of Oxford: “The increase in killings reflects the continuation of a trend in rising violence against civilians, largely attributable to inadequate implementation of the 2016 peace accord with the FARC guerrilla, particularly by the Duque administration. Within this context of increasing insecurity, 2022 was an election year, and many political activists were threatened, especially those campaigning for Petro. Additionally, some armed groups ramped up activities to demonstrate their power and obtain greater leverage in eventual negotiations with the Petro administration. Other killings suggest a backlash to the increased participation of social movements in the national agenda under Petro, such as the Regional Dialogues that give agency to local actors. Petro has taken important steps to address this violence, including restarting the National Commission for Security Guarantees which was inactive under Duque, and implementing an emergency plan to protect the lives of social leaders. But his main objective is to end the conflict with the remaining armed groups and achieve ‘total peace.’ His government has begun peace talks with the National Liberation Army guerrilla and has created the legal framework for negotiations with other armed groups such as the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC) and dissident FARC factions that either did not sign the 2016 peace accord or rearmed after demobilization, and cease-fire agreements are under development with many of these groups. Reducing violence in Colombia will depend on successfully synchronizing shorter-term mechanisms to prevent targeted assassinations with the long-term strategy of ending the conflict with all groups and building sustainable peace.”

Jamie Hagen, lecturer in international relations at Queen’s University Belfast: “The targeted killings against human rights defenders in Colombia is in line with the rise of targeted violence toward those resisting patriarchal violence globally. This is most evident when looking at the harm faced by those protecting the rights of lesbian, bisexual and transgender women in Colombia in the transitional justice process. Human rights activists are targeted for challenging gender norms. Initiatives like La Alianza Cinco Claves offer specific entry points for supporting those social leaders involved in feminist activism in Colombia. In a recent conversation, Colombia Diversa hosted engaging LGBTQ human rights defenders and women’s peacebuilders in Colombia, and a number of concerns were raised regarding the limitations of the current security responses. A key concern was the lack of collective community level care offered, with all protection measures instead focusing on individuals. Participants argued for the need for building a feminist, demilitarized approach to security that can confront lack of access to justice, femicidal violence and patriarchal justice systems together. Human rights defenders spoke of the current security efforts relying on individual protection approach that is costly and isolating. They also highlighted the need for the participation of LGBT people in developing the processes of risk analysis, along with the initial construction of appropriate security measures. Finally, they argued that to take LGBT social leaders experiences of risk and safety into account, it is important to also design protections for transgender people through instruments initially designed to protect cisgender women.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

Since the outbreak of the drug war, Ciudad Juárez has been plagued by unfathomable levels of violence and corruption, leading to thousands of human rights violations.

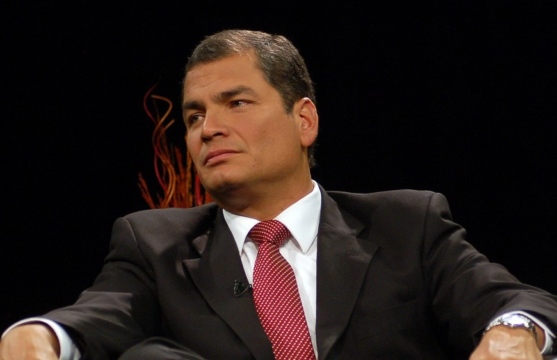

In June, President Correa issued a decree creating new procedures for NGOs to obtain legal status. What are its implications?

Colombia last year recorded its highest-ever rate of killings of human rights activists. // File Photo: Radio Nacional de Colombia.

Colombia last year recorded its highest-ever rate of killings of human rights activists. // File Photo: Radio Nacional de Colombia.