Impact of Lower Commodity Prices on Latin American Growth

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra is facing a new political crisis, left with no ministers on Tuesday after Congress refused to approve his recently appointed cabinet in an unexpected no-confidence vote. How significant is the no-confidence vote in Vizcarra’s cabinet, and how big of a blow is it for the president in terms of his leadership and political capital? What was the reasoning behind Congress’ decision, and to what extent is it justified? What implications will the forced cabinet change and tensions between the president and Congress have for Peru’s response to the health and economic crises it is facing?

Julio Carrión, associate professor and associate chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware: “This event shows once again the severe dysfunction of Peru’s political institutions. The no-confidence vote is not only a significant blow to President Vizcarra, but also for the prospects of governance in Peru. Vizcarra is constitutionally banned from running for immediate re-election. The current Congress, elected last January, will no longer exist next July, and none of its members can be re-elected. You would imagine that this shared condition, in the context of a raging pandemic and deteriorating economic conditions, would foster some collaboration between the president and Congress. Unfortunately, most political parties in Peru are mere extensions of business or private interests. The ‘parties’ in Congress run the gamut from followers of religious syncretism, to owners of diploma mills, to fujimoristas, and ethnonationalists. In the absence of real parties, the legislature is fragmented into nine or 10 congressional representations (who can really keep count?), and the president himself has no congressional party. Vizcarra has denounced the vote as payback for his refusal to remove the minister of education who, as head of the state office in charge of licensing universities, denied those licenses to numerous diploma mills. The president of Congress said that the problem was with three ministers, not just the minister of education. César Acuña, the owner of a large private university and leader of the party with the second-largest number of seats in Congress, said the problem was a lack of serious plans to combat the current crisis. Perhaps the public rejection of congressional intransigence will force it to be less confrontational. It will be difficult for Congress to reject another prime minister, even if the new cabinet includes the current minister of education. But the likely retreat will only intensify the desire in Congress to get back at Vizcarra. The prospects of improving governance and responding effectively to the economic crisis are dismal. The only consolation is that general elections are scheduled for next April.”

Cynthia McClintock, professor of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University: “The pandemic has been devastating to Peru; its fatality rate and GDP plummet are among the worst in the world. Tragically, the catastrophe will be exacerbated by Tuesday’s no-confidence vote. The vote was unexpected because President Vizcarra had just proposed a pact with Congress, and his new cabinet, appointed in mid-July and led by veteran politician Pedro Cateriano, had not been particularly controversial. In addition, it was unexpected because the Congress, newly elected in January, is composed largely of ideological moderates; only 12 percent of the seats are held by Keiko Fujimori’s party, which had previously obstructed Vizcarra at every turn. However, Vizcarra has no party of his own, most of the nine parties in Congress are tenuous and re-election of legislators is prohibited; accordingly, many legislators are pursuing their own interests. In particular, Alianza para el Progreso and Podemos Perú legislators have stakes in for-profit universities and are resisting government reform efforts. For its part, Peru’s left worries that, amid the pandemic, Vizcarra has become too favorable toward mining companies. Perhaps most important is legislators’ desire for payback against a president who has criticized them (but not himself, despite Peru’s current straits) and—simply—general frustration. Now, Vizcarra must find a new premier and decide whether or not to reappoint cabinet ministers; so, urgent work will stall. Potentially strong nominees may fear irresponsible congressional challenges and will serve only until next July, when a new president will be inaugurated; they may not want the jobs. Peruvians are likely to blame the Congress more than Vizcarra, but the turmoil—and the image of turmoil—significantly damages all political institutions and the country as a whole. Although the 2021 elections will go forward, concerns may mount.”

Francisco Durand, professor of political science at the Catholic University of Peru: “The division between the president and the new Congress has reached a crisis point. A provisional, orphan president (with no official party) and the Cateriano cabinet underestimated the congressional voting blocs. Two major problems stand out. First, the ‘let’s promote big mining’ message ignored environmental and social concerns. Thus, the left (Frente Amplio) and the religious popular sect (FREPAP) chose the no-confidence vote. Second, four parties financed by for-profit universities (Acción Popular, Podemos, Unión por el Perú and Alianza para el Progreso) voted against or abstained because they conditioned their support on the removal of the minister of education, who remained in the Cateriano cabinet. Vizcarra is now in a weaker position. His ratings are still strong, but the problems with Covid-19, still raging, and the economic needs of the people, two issues sidelined by the Cateriano cabinet, need to be strongly addressed. Vizcarra has an opportunity to refocus his agenda and present a cabinet that can win approval in Congress. The other scenario is more worrisome: Congress may try to impeach the president. In either case, Peru has entered a time of uncertainty that will stall investment, already affected by Covid-19. Most likely, Vizcarra will muddle through until next April’s election. Survival is now a priority for everybody, including politicians.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

Peru’s growing urban middle class is one of the country’s greatest assets, but it also brings political and governance challenges.

In Peru, it is generally known that a better quality education could build citizens, who are better prepared for the democracy and modern and flexible workers, who would help reduce poverty. However, over the last decade- as well during the previous one- many factors have prevented the improvement of the…

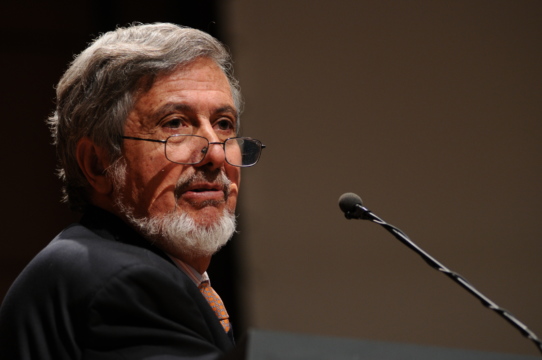

In a televised address Tuesday, Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra (pictured) blasted lawmakers for their no-confidence vote against his cabinet that is led by Prime Minister Pedro Cateriano. // Photo: Peruvian Government.

In a televised address Tuesday, Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra (pictured) blasted lawmakers for their no-confidence vote against his cabinet that is led by Prime Minister Pedro Cateriano. // Photo: Peruvian Government.