New Bipartisanship Over Haiti is Promising

The sudden U.S. presidential unity on Haiti is promising, because Haiti has long been the subject of bitter partisan bickering in Washington.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Haiti’s Senate, the country’s last democratically elected institution, has adjourned with no new members to convene a new term. The 10 remaining senators who had been representing the country’s 11.5 million people–because Haiti failed to hold legislative elections in 2019–saw their terms expire on Jan. 10, leaving the country without a single lawmaker in its National Assembly. The last time Haiti lacked elected officials was during the bloody regime of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who fled the country in 1986 after a popular uprising. What does the absence of any elected officials mean for Haiti? What can Prime Minister Ariel Henry, who assumed leadership after President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in July 2021, do to remedy the situation? How likely is the international community to step in?

Peter Hakim, member of the Advisor board and president emeritus of the Inter-American Dialogue: “Haiti is a dying country. Partly, it is strangling itself. But misdirected ‘aid’ and many other external interventions has long contributed to Haiti’s decline. There are deadly cholera epidemics, massive hunger and growing starvation, minimal medical facilities, devastating joblessness, fuel and transport scarcity, a lack of clean water, a dearth of education opportunities, natural disasters, farmland transformed into wastelands and not a single elected official in the country. Since the hellish murder of President Jovenel Moïse some 18 months ago, the top official has been a man empowered by the United States who has accomplished little or nothing and remains suspected of involvement in the assassination. In many areas, life-and-death power is in the hands of vicious criminal gangs. So, what is the United States doing to help the 11 million Haitians, many of whom want just to flee? Not much. Aid levels are pitifully matched against Haiti’s needs. Today’s U.S. strategy seems mostly limited to pressing Canada and a few other nations to take more leadership on Haiti and calling on the Haitians themselves to reach consensus on how the United States should proceed. This is not a strategy; it leads nowhere. The United States must become heavily engaged or nothing will be done. This is not a call for marines, which Haitians widely reject, or even for a new massive aid program. What’s needed is a serious, sustained, vigorous diplomatic initiative to develop an understanding of the players, politics, money trails and power dynamics of Haiti and work with intensity and patience to encourage and persuade Haiti’s many disparate political, business and civil society groups toward a consensus on a strategy for cooperation with the United States and the international community. The effort requires a talented leader reminiscent of then-OAS Secretary General Luigi Einaudi, who traveled regularly to Haiti during another crisis, or Bernard Aronson, a key U.S. peace negotiator in El Salvador, or Bill Richardson, who negotiated hostage releases and other issues worldwide—all along with an able, dedicated staff. The Biden administration should at least try to do what’s right and humane in Haiti.”

Sibylle Fischer, associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese at New York University: “The departure of the last elected officials from Haiti’s government on Jan. 10 brings to a head a crisis of legitimacy that has been brewing for years. Given the catastrophic security situation and the questionable legitimacy of the sitting government, there is no authority left that can guarantee free and fair elections. Yet, Henry’s request of a ‘rapid response force’ to restore security is in all likelihood an attempt to hold on to power. Given that, and the dismal track record of international interventions in Haiti, most Haitians are adamantly opposed to an intervention. There are alternative scenarios. It helps to consider why it is that a year and a half after the assassination of Jovenel Moïse no progress has been made toward resolving the constitutional crisis. An under-appreciated factor is that, just like the prime minister himself, Haiti’s neighbors and the international actors in general have failed to engage with civil society groups. The Montana Accord of the summer of 2021 is a case in point. Clearly, the Montana transition plan was an extra-constitutional response to the crisis, but it put Haitian civil society and the Haitian people in the driver’s seat. In the face of the collapse of the constitutional order, any such bootstrap operation requires moving beyond formalistic notions of democracy and legitimacy and instead embracing a ‘constituent moment,’ a refounding of political society ‘by and for the people.’ Shoring up dominant political actors in the name of stability and continuity will only perpetuate the crisis.”

James Morrell, executive director of Haiti Democracy Project: “The Haiti Democracy Project advocated that the United Nations stay. With the U.N. mission’s assistance, but with Haitians always in the lead, Haiti beat back the gangs. It inaugurated four presidents. It held nine elections. Since the mission was foolishly withdrawn, the gangs have spewed onto the streets, the president was assassinated, and no election has been held. Much worse is to come if Haiti is bereft of international solidarity. The Biden administration is entering its third year; it still has freedom of action. It did well to sanction some of the bad actors. But it is still trying to slough off the main job to Canada. That just leaves the disaster to fester on and explode in an election year, handing the Republicans a perfect issue. Canada has set as a condition some degree of consensus among the Haitian politicians. But you will never get that; they will never agree. In their scramble for the spoils of office, some will always see an advantage in objecting. But the political class speaks for relatively few Haitians. In a recent radio poll on the foreign question, 81 percent said to bring them on. They will take help from wherever it comes. Pamela A. White, a former U.S. ambassador to Haiti whose heart has never left Haiti, decries Washington’s indifference. ‘Boots on the ground now,’ she pleads. The gangs are expected to be on the prowl again in the coming weeks. Without a force to back up the police, deliveries will be blocked, clean water will be scarce, and thousands of malnourished children will be thrust into cholera’s death maw. Washington needs to get on with the job.”

Georges Fauriol, fellow at the Caribbean Policy Consortium and senior associate at the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS): “The absence of elected officials at both national and local levels only highlights the state of Haiti’s collapsed governance apparatus. More importantly, it places even more pressure on interim Prime Minister Ariel Henry to construct a plausible and durable alternative. This is in fact the backdrop to the emergence of the Dec. 21 ‘Consensus,’ whose critical feature sets in motion a ‘Transition Council.’ Mostly manipulated by Henry (with assistance from the U.N. representative in Haiti), the three-member council (rather than the anticipated five) has an audacious task list that borders on the unrealistic. It includes assisting Henry with reconstructing the national election council (CEP), and supporting the process toward constitutional reform, let alone putting in place a plan to address the nation’s public security needs–for example, street level insecurity. With informal references to a one-year transition timetable that includes national elections, the Dec. 21 agreement may appear to international actors as a promising platform toward national consensus. But the Achilles’ heel is that it retains Henry as the key Haitian political actor through the duration of the Transition Council’s tenure. In its Haitian political context, that is probably a nonstarter and invites the need for some creative flexibility among Haiti’s key actors. What remains perplexing is that Washington is perfectly aware of all these shortcomings but appears reluctant to choreograph an international diplomacy (including Canada, the European Union, the United Nations and Caricom) to ensure that key Haitian actors coalesce around a viable, legitimate consensus path forward.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The sudden U.S. presidential unity on Haiti is promising, because Haiti has long been the subject of bitter partisan bickering in Washington.

The worldwide outpouring of support for Haitians from governments and ordinary citizens has been extraordinary. But this heroic phase of the emergency response is drawing to a close.

After a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck Haiti, the aftershock reached China in ways that few anticipated.The earthquake forced Chinese leaders to navigate the tricky politics of disaster relief.

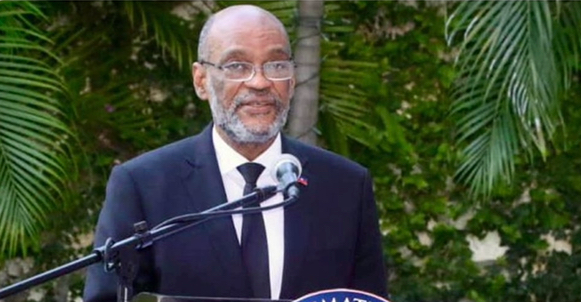

Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry leads a country with no democratically elected lawmakers and where gangs have tightened their grip. // File Photo: Haitian Government.

Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry leads a country with no democratically elected lawmakers and where gangs have tightened their grip. // File Photo: Haitian Government.