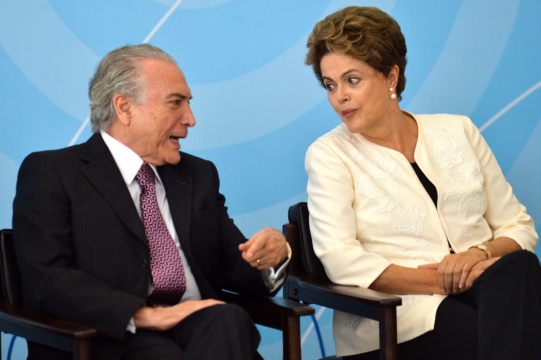

Não há guinada à direita

Pesquisador americano Michael Shifter diz que população, cansada, fez aposta em Temer, mas que PT ou esquerda podem voltar

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Peruvian President Pedro Castillo, who has been in office just eight months, in late March survived a second impeachment attempt against him. Castillo’s opponents have tried to oust him on the grounds of alleged “moral incapacity,” the charge that was also leveled against former President Martín Vizcarra, who was removed from office in November 2020, ushering in a period that led Peru to have three presidents in fewer than 10 days. In a speech to Congress in mid-March, Castillo said Peru “is going through an institutional crisis” amid the instability, and analysts now see political turmoil as a major deterrent to investment in the country’s once-steady economy. What is at the root of Peru’s political instability, and what can be done to break the political paralysis brought on by repeated challenges to the president’s mandate? Could constitutional reforms calm the frequent political upheaval and, if so, what should they involve? How are investors dealing with the uncertainty, and how are key sectors, such as mining, performing amid so much volatility?

Pedro Francke, former Peruvian economy and finance minister: “There are two sources of structural instability in Peru. The first is the constitutional provision that allows Congress to impeach the president for ‘moral incapacity’ and without adequate judicial processes, and this must be reformed. The second is the permanent mistrust of citizens in their government, Congress, political parties and the media, with a patrimonial state and serious ethnic and regional inequalities. The victory of Pedro Castillo last year was the manifestation of the dissatisfaction of discriminated groups, who were hoping for profound change from a Castillo government. The institutional instability was aggravated by the 2021 electoral results that gave Castillo the narrowest of victories, with a scattered Congress and the refusal of powerful economic groups to accept the results—followed by Castillo’s own wavering and his difficulties in forming an effective government. Popular demand today is a mix of the need for solutions to urgent issues, like food and fuel prices, with the feeling that deeper and more profound changes are needed—and that historical injustices and mistreatment must be addressed. In my opinion, the demand for a response to the economic pain caused by inflation is at the forefront, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic that impoverished many families. The late, clumsy and erratic response of the Castillo government to the recent wave of protests has greatly weakened its legitimacy. Among investors, doubts about possible changes in the economic model have dissipated, but external shocks and the rise in interest rates by the central bank, coupled with the general ungovernability and social disorder in the country, have resulted in a decline in investment.”

Mercedes Aráoz, former second vice president of Peru and a professor of economics at Universidad del Pacífico: “Pedro Castillo’s management style as president is a mixture of improvisation, inefficiency, deep irresponsibility and a lack of integrity. In a short time, he has squandered his political capital and lost his legitimacy. Today almost eight out of 10 Peruvians disapprove of his presidency. The country has seen inflation in food and fuel, which is the product of external factors, but Castillo has no contingency plan to deal with it, other than to impose a curfew in Lima after widespread protests. But the current crisis predates Castillo—it began in the Fujimori era with the weakening of political parties that operate without ideology or doctrine, the triumph of outsider candidates and the appearance of regional movements led by ‘caudillos’ (populist strongmen). The second factor that has contributed to today’s crisis is a failed decentralization process, where regional governors have too much power and manage important economic resources without accountability. Furthermore, the rise in informal political groups linked to illicit activities such as drug trafficking, illegal mining, informal transportation, etc. has not helped matters. There are people in Congress who represent those interests, which lead to under-the-table deals being made. Added to this is the institutional weakness of the justice system and its politicization. We have a perfect storm that is impacting the economy and increasing uncertainty for investors, especially in sectors such as mining. Regardless of how the crisis is resolved in the short term, deep reforms must be made in the political and judicial systems, introducing a better balance of power in government by strengthening political parties, as well as fixing the issues surrounding decentralization.”

Cynthia McClintock, professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University: “Although political instability is very problematic, misgovernment can be even more so. The vague charge of ‘moral incapacity’ provides an exit possibility for a government that has become untenable, as Castillo’s government appears to be today. Impeachment requires a two-thirds vote of Peru’s Congress—a larger percentage than would be necessary to oust the executive under most parliamentary rules. The ‘moral incapacity’ provision in the Constitution led to the resignation of Alberto Fujimori in 2000; he was guilty of egregious corruption and human-rights abuses. Although the ‘moral incapacity’ provision also enabled the questionable oustings of Martín Vizcarra in 2020 and Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in 2018, evidence of Vizcarra’s corruption was compelling and Kuczynski was struggling with conflict-of-interest allegations. In the case of Castillo, the charges of corruption by his former friend, lobbyist Karelim López, are also persuasive. Further, Castillo consistently makes high-level appointments on the criterion of political allegiance, not competence. A broad-based cabinet with well-qualified ministers is especially important because of Castillo’s limited support from the start; running for a far-left party in the 2021 election, Castillo tallied only 19 percent of the first-round vote and would not have won the runoff if his rival had been almost any of the other candidates except Keiko Fujimori. Among the ministers without sufficient experience is the Energy and Mines Minister Carlos Palacios; he has been unable to resolve the continuing intense conflicts between numerous mines and near-by communities—a top priority for Peru’s investors. Peru’s oil company, Petroperú, also struggled with incompetent leadership. Previously, impeachments were followed by effective governments by Congress speakers—in 2000, Valentín Paniagua, and in 2020, Francisco Sagasti. One necessary reform is to allow immediate re-elections of legislators. The ban on re-election seriously shortens legislators’ time perspectives.”

Claudia Navas, senior analyst at Control Risks: “The ongoing instability in Peru confirms the overall dysfunctionality of the political system, regardless of who is in power. In large part, the dysfunctionality is strongly rooted in the weakness of the party system. Political parties have become bureaucracies that work to further their own political and economic interests rather than representing the interests of the population. Peru needs a comprehensive political reform that, among other things, promotes citizen participation in the party system and strengthens internal rules for selecting candidates within political parties. Measures to ensure the suitability of those holding political power are also required. A reform is also needed to introduce clear criteria for Congress to impeach a president on the grounds of ‘moral incapacity.’ Peru’s pro-business fundamentals and a strong economy have mitigated the damage of long-standing political instability on the country’s business environment. However, in 2021, Peru experienced its highest level of capital flight of the past 50 years. Funds equivalent to 7.4 percent of GDP left the country, according to the Central Reserve Bank of Peru. This capital flight was driven by the polarization and uncertainty surrounding Castillo’s 2021 election victory due in large part to his promises to nationalize key industries, such as mining. Ultimately, this instability will keep holding the country back as risk-averse investors seek more politically stable destinations.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

Pesquisador americano Michael Shifter diz que população, cansada, fez aposta em Temer, mas que PT ou esquerda podem voltar

On June 4, the Inter-American Dialogue, the Center for Reproductive Rights, and the International Planned Parenthood Federation co-sponsored an event titled “The Crisis of Democracy and Women’s Rights in the Americas.”

Iván Duque, a conservative former senator, on Sunday won Colombia’s presidential runoff election. What does it mean for the country?

President Pedro Castillo on Thursday ordered the armed forces to supervise Peru’s highways for the next month in the face of trucking blockades over inflation that have halted travel and commerce. // File Photo: Peruvian Government.

President Pedro Castillo on Thursday ordered the armed forces to supervise Peru’s highways for the next month in the face of trucking blockades over inflation that have halted travel and commerce. // File Photo: Peruvian Government.

Video

Video