Which Mexico for Obama?

When President Obama meets this week with President Peña Nieto, he will be visiting a country that was much maligned throughout his first term.

This post is also available in: Español

WASHINGTON - For Latin America, the G20 Summit next week in Buenos Aires was supposed to be a celebration.

This will be the first annual meeting of the world’s major powers in South America—and for many, the significance was meant to go further. The host, Argentine President Mauricio Macri, had hoped to tout an economic transformation and continue opening his country to the world. Coming just after presidential elections in the other two Latin American G20 members, Brazil and Mexico, this was to be a moment of new energy, showing how Latin America can help shape the global conversation. The meeting in Buenos Aires will even be Donald Trump’s long-awaited first trip to Latin America in office, having skipped April’s Summit of the Americas.

Yet, on the eve of the meeting, it seems those expectations will be unmet. Macri’s attempts to jump-start the moribund Argentine economy, constrained by tough politics and negative external factors, have disappointed. His push for new investment has struggled to gain traction in a world where protectionism and anti-globalism are suddenly very much in vogue. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts Argentina’s economy will contract this year and next, with inflation inching past 40 percent. Macri is almost sure to face a tough reelection fight next year.

Meanwhile, hemispheric relations have decayed considerably over the last two years. In dealing with its southern neighbors, the Trump Administration has been mostly absent and disorganized. Trump’s few overtures have focused almost exclusively on security, immigration, and confronting left-wing authoritarians in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua.

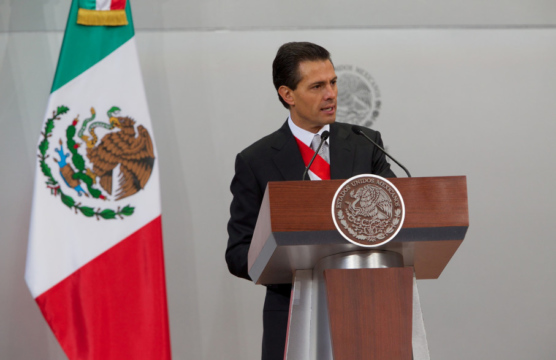

And the United States isn’t the only country upsetting the regional dynamic. The other two Latin American leaders in the G20—Brazil’s Michel Temer and Mexico’s Enrique Peña Nieto—are the lamest of lame ducks. In July, Peña Nieto’s party was swiftly shown to the door as left-wing populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador won in Mexico’s biggest landslide since democratization. López Obrador formally takes office on December 1st, the second day of the Summit.

Brazil went the other direction, electing a right-wing firebrand, Jair Bolsonaro, who takes office in January. Bolsonaro was invited, but is likely to skip due to poor health. Still, he will overshadow Temer, an unelected president who took office after his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached and currently has a 2 percent approval rating.

Together, Bolsonaro and López Obrador represent a radical change in the status quo for the Americas. But their main unifying feature is nationalism and a desire to focus on domestic challenges—a new era of Latin American engagement with the world seems unlikely.

Even Latin America’s most pressing crisis, the manmade disaster in Venezuela, is unlikely to be part of the conversation—despite Macri’s request during last year’s G20 for special attention to the human rights situation there. As Venezuela continues to spiral into a deep political, economic, and humanitarian crisis, its citizens are desperately fleeing—approximately three million people have emigrated. Latin American countries, especially Colombia and Peru, have borne the brunt of what is now the world’s largest migrant crisis. During a March meeting of G20 finance ministers, ten countries agreed to request funds from the IMF to assist with resettlement costs. They also agreed to bilaterally pressure the government of Nicolás Maduro. But at the Summit itself, most G20 countries—especially Venezuela’s allies Russia and China—are unlikely to dwell on Venezuela.

Overall, Latin America will be a mostly peripheral presence. The signing of the new NAFTA replacement, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), may be the only exception, but this will take place quickly and on the sidelines.

Instead, global tensions will dominate, especially between the United States, Russia, and China. Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin are expected to hold a “long and thorough meeting,” while Buenos Aires will be Xi Jinping and Trump’s only opportunity to meet before US tariffs on a significant part of Chinese imports increase to 25% on January 1st. According to a leaked draft of the joint G20 statement obtained by the Financial Times, there will be no explicit commitment to fighting protectionism, unprecedented in the history of the forum.

And if that weren’t enough, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman will attend just as other world leaders are coming to accept that not only did he likely order the execution of Jamal Khashoggi—a veteran Saudi journalist, US resident, and Washington Post columnist—but also that Trump intends to stand by him.

To be sure, Macri can and should labor to be a dynamic host, and Argentina is right to advocate for openness and multilateralism—perhaps the worst impulses of nationalism and protectionism can continue to be blunted. The world needs dialogue and cooperation, now as much as ever, and this meeting is at least a chance for debate.

However, the rest of Latin America—in particular, Brazil and Mexico—should look beyond the Buenos Aires G20. Both Bolsonaro and López Obrador should do more to set their foreign policy agendas, consider how their countries can play a positive role in hemispheric and global conversations, and weigh seriously the risks of further global dislocation. Above all, the region has an essential role to play in fighting corruption and climate change, and in managing the waves of migration (from Venezuela and elsewhere) that can only be expected to grow in coming years.

When President Obama meets this week with President Peña Nieto, he will be visiting a country that was much maligned throughout his first term.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto marks 100 days in office. Is he focusing the beginning of his presidency on the right goals?

With crude oil prices down 25 percent since June and holding at roughly $86 a barrel on Tuesday, Venezuela is getting nervous.

Casa Rosada / Wikimedia / CC BY 2.5 AR

Casa Rosada / Wikimedia / CC BY 2.5 AR