IACHR Report on Citizen Security & Human Rights

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

This post is also available in: Español

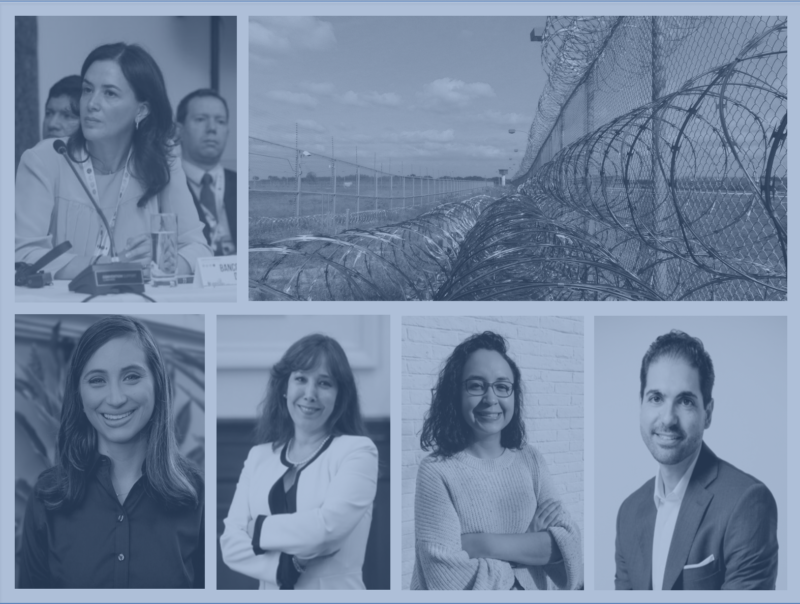

On April 14, 2021, the Inter-American Dialogue hosted the online event “The Covid-19 Pandemic and Prison Policy in Latin America”. The panel discussed a new report published by the Dialogue’s Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program authored by María Luisa Romero, Luisa Stalman, and Azul Hidalgo Solá, which examined how the Covid-19 pandemic impacted prison policies in Latin America. The event was moderated by Michael Camilleri, director of the Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, and featured analysis from Nathalie Alvarado, head of Citizen Security and Justice at the Inter-American Development Bank; Sara Vera López, Latin America and monitoring advisor at the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT); María Luisa Romero, member of the Inter-American Dialogue, former minister of the Government of Panama and member of the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture; and Susana Silva, president of the Peruvian National Penitentiary Council.

Camilleri described the motivation behind the report, noting that many precarious conditions that already exist in prisons in Latin America, such as overcrowding, had the potential to exacerbate the spread of Covid-19 and present an acute challenge to prison administrators. Romero, outlining the broad conclusions of the report, noted that the pandemic was a catalyst for much-needed reforms, as it forced authorities to mobilize quickly to mitigate future risks of infection. She pointed out how many of these measures implemented during the pandemic, such as increasing food rations and improving access to water, should be a priority even without a pandemic. However, the health crisis demonstrated that when governments have the political will and urgency to act, they can act quickly. While Romero noted that less than 5% of the prison population was released due to policies implemented as a direct consequence of the pandemic, these efforts left an important precedent that it is possible to reduce prison populations and explore alternative punitive measures – a precedent that hopefully will inform prison policies in the future after Covid-19.

Camilleri highlighted the efforts that the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) made since the beginning of the pandemic to facilitate regional dialogue so prison administrators and government officials could share challenges and responses to the Covid-19 pandemic in the prison context. Alvarado remarked that “prisons are often forgotten spaces” for the majority of the population, but after high-profile riots due to the suspension of family visits and lack of protective measures, political leaders were pressured to pay more attention. Citing IDB data, Alvarado explained how 58 percent of prisoners did not have a bed to sleep on, 20 percent did not have access to drinking water, and 29 percent did not receive any kind of medical attention. The IDB convened government representatives from more than 16 countries, as well as the President of the Red Cross for early dialogue where officials identified a common framework for prison policy during the pandemic. Alvarado pointed at engaged participation as an indicator for future similar forums to analyze what actions implemented during Covid-19 were most effective and should remain even in a post-pandemic context.

López explained which measures had been adopted by Latin American governments so far in order to improve prison conditions during the pandemic. She noted how decongestion measures to address overcrowding were initiated by governments, but they lacked corresponding processes to assist people who were recently released, such as help obtaining employment and housing. She pointed out how greater interinstitutional cooperation was needed in order to create more sustainable policies that incorporated views from torture prevention mechanisms, people deprived of their liberty and their families, and local advocacy groups. Both López and Romero agreed that the pandemic highlighted the necessity to create preventive and not reactive measures to improve prison conditions. Romero argued that the pandemic showed that it is necessary to think of imprisonment beyond the first and only penal measure, as overcrowding has been well-documented to violate human rights and severely endanger the public health of its community. She noted that many of the people who were released early due to policies implemented in the pandemic should not have been imprisoned in the first place. Alvarado pointed out some measures that had been implemented by some countries in the region, such as establishing a more rigorous visiting protocol, including temperature checks, and taking advantage of technological tools for telemedicine and virtual education, which were successful in preventing the spread of Covid as well as allowing prisoners to have social contacts, essential to their rehabilitation and engagement.

As many of these measures require considerable political will, Camilleri asked Romero about the political cost of implementing prison reform, and how these costs could affect future progress. Romero explained that prisons, in general, are the “last priority” for the government, as public opinion tends to center on the punitive rather than reformative aspect of prisons. She emphasized how necessary it is to center human rights in any prison policy, and how important it is to educate the public on why imprisonment is not and should not be the only way for citizens who do not present a risk to others to serve out a sentence. She encouraged governments to market these policies as ones that ultimately benefit the entire community, reiterating that “prison health is public health”, and that preventing prisons from being overwhelmed is overall beneficial to the general public health systems.

Finally, the panel discussed ways that governments, civil society groups, and international organizations can join efforts to improve the systematic weaknesses in prison systems. Silva pointed out how prison administrators are overall administrative and not political bodies, and how channeling political will via awareness campaigns as well as framing reducing overcrowding as a public health issue could support administrators’ more ambitious reform goals. Romero highlighted how international organizations have already played a crucial role in advocating for people deprived of their liberty during the pandemic, and that they should have further collaborations with civil society groups and governments to create comprehensive policies that address human rights concerns in the near future. Romero ended the panel on a positive note, remarking that “if every crisis is an opportunity, our experience during the last year shows that measures that have been taken in response to this crisis have enormous potential to do more good if we maintain them”.

Citizen security remains a top concern for most Latin American governments as crime and violence spiral out of control and cripple political and economic institutions in the region.

Since the outbreak of the drug war, Ciudad Juárez has been plagued by unfathomable levels of violence and corruption, leading to thousands of human rights violations.

In June, President Correa issued a decree creating new procedures for NGOs to obtain legal status. What are its implications?

Main Photo: jodylehigh / Pixabay / CC0

Main Photo: jodylehigh / Pixabay / CC0