Violence & Impunity: Protecting Journalists in Colombia & Mexico

Violence against journalists is fortunately uncommon in many Latin American countries. But in some parts of the region it is of great concern.

On July 16, 2019, the Inter-American Dialogue, in partnership with Reporters without Borders, hosted an event called, “No News is Not Good News: Combating Pervasive Violence Against Journalists in Mexico." The event featured opening remarks by Sabine Dolan, Interim Executive Director of Reporters Without Borders USA (RSF), and was followed by a panel discussion featuring Maureen Meyer, Director of the Mexico Program at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA); Alejandra Ibarra Chaoul, Founder and Lead of Democracy Fighters; Dolia Estévez, weekly columnist for SinEmbargo.com and freelance journalist; and Edison Lanza, Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Michael Camilleri, director of the Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, moderated the discussion.

Dolan opened the discussion by stating that, historically, countries at war are the most dangerous for the press, but with seven killings of journalists in 2019 alone, Mexico, a country not at war, is now the most dangerous country to be a journalist. As Dolan stated, “In Mexico, impunity rules the day.” She left two questions for the panelists: How do we handle the Mexican judicial system that fails at protecting journalist’s profession? And, what do we do about the 99 percent of crimes against journalists that remain unsolved?

Estévez began by saying that there is currently a crisis situation for journalists in Mexico, with the potential of getting worse. Estévez highlighted that, while organized crime groups have born the blunt of blame for violence against journalists, a large share also lies with corrupt government officials at municipal, state and federal levels. This situation has not improved under the administration of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, and Mexican authorities seem unable to stem the violence. Lopez Obrador’s rhetoric against journalists, which he calls “fifi”, meaning conservative and elitist, creates an environment in which journalists are more vulnerable and exposed. Estévez asserted that the mechanism for the defense of journalists is not working, has never worked, and Lopez Obrador’s budget cuts across the board exacerbate the problem.

Ibarra Chaoul described the mission of Democracy Fighters, an archive that aggregates and disseminates the works of journalists killed in Mexico. The archive tries to prevent journalists killed for doing their job from becoming a statistic and for their pieces being left unread. Ibarra Chaoul stated, “Journalist’s legacies should not be their deaths, their legacies should be their words.” Because the aim of killing journalists is to silence them, Democracy Fighters aims to make the crimes costlier and recover material which could help solve these cases. Ibarra Chaoul stated that most of these crimes occur with respect to local and online outlets in coverage of politics or human rights. Importantly, some of the murders are targeted against journalists, but others are part of the larger campaign against freedom of expression that journalists suffer from in their own private lives.

Lanza addressed his key findings as Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression during a visit to Mexico. He stated that, during the Peña Nieto administration, the government slowly improved the mechanism protecting journalists in Mexico and the issue of impunity. However, Lanza has seen no signs of this type of commitment during the seven months Lopez Obrador has been in office. For the problematic situation facing journalists in Mexico to improve, the protection mechanism needs more investment and the General Prosecutor needs more autonomy from the government. Lanza stated that in order to reform the prosecutor’s office, the government must redirect resources, work on capacity peopling, create transparent policies, and move the prosecutor into the field.

Meyer began by stating that the mechanism is at best a Band-Aid, and that the bigger problem is if attacks against journalists are not investigated, these crimes will continue to occur. The biggest challenge for investigating these cases is with resources. This year, the Undersecretary of Human Rights saw his budget sharply reduced, and the separate budget for protection is three million dollars less than last year’s. In March of this year, the protection measure had 831 beneficiaries with only 35 staff; showing that while the number of staff has not changed over the last few years, the number of beneficiaries continues to rise. Meyer claimed that from 2012-2018, 3% of state level prosecutions went to federal court. On the federal level, for crimes against freedom of expression, less than 12% of cases were taken to court and only 5% resulted in a conviction. The selection of the new prosecutor for human rights will be influential in how future crimes are investigated and the strength of the federal courts.

Meyer also reiterated the importance of protection for journalists at the state level in Mexico. Primary responsibility for protecting journalists falls with the states, who are often not doing their job. While the US government could do more in allocating funding towards this issue, we also lack credibility in defending journalists in Mexico because the Trump administration has not respected its own press.

The panel was followed by a question and answer session, where the panelists primarily addressed the questions of where journalists and reporters can go when the government does not hold perpetrators accountable, and what can be done to make the government more accountable. Estévez said that in systems with weak checks and balances, journalists are necessary to hold the government accountable. Lanza stated that the core problem is not of the lives of journalists, but rather of the right to know in Mexico. He recommended that the government create a new public system for media, which would be a step forward in relation to diversity and pluralism in the media system. Meyer mentioned the contingency plan, with that in Chihuahua, Mexico being a successful example, as an innovative part of the mechanism that employs state authorities, human rights defenders, journalists and the national human rights commission. The plan is holistic in that it utilizes both the federal government and also state commitment.

Violence against journalists is fortunately uncommon in many Latin American countries. But in some parts of the region it is of great concern.

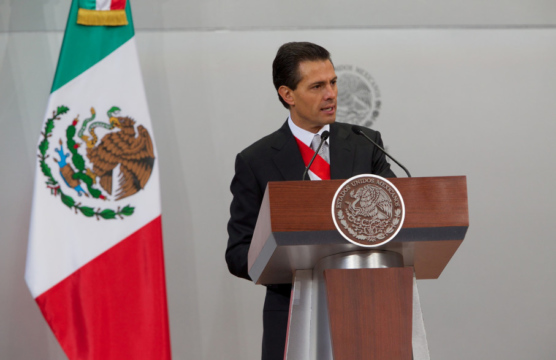

When President Obama meets this week with President Peña Nieto, he will be visiting a country that was much maligned throughout his first term.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto marks 100 days in office. Is he focusing the beginning of his presidency on the right goals?

Tamar Ziff / Inter-American Dialogue

Tamar Ziff / Inter-American Dialogue