The Earthquake’s Impact on Remittances

The earthquake in Haiti has exacerbated an existing distress during the international recession and increased uncertainty of what to do and how to help.

INTRODUCTION

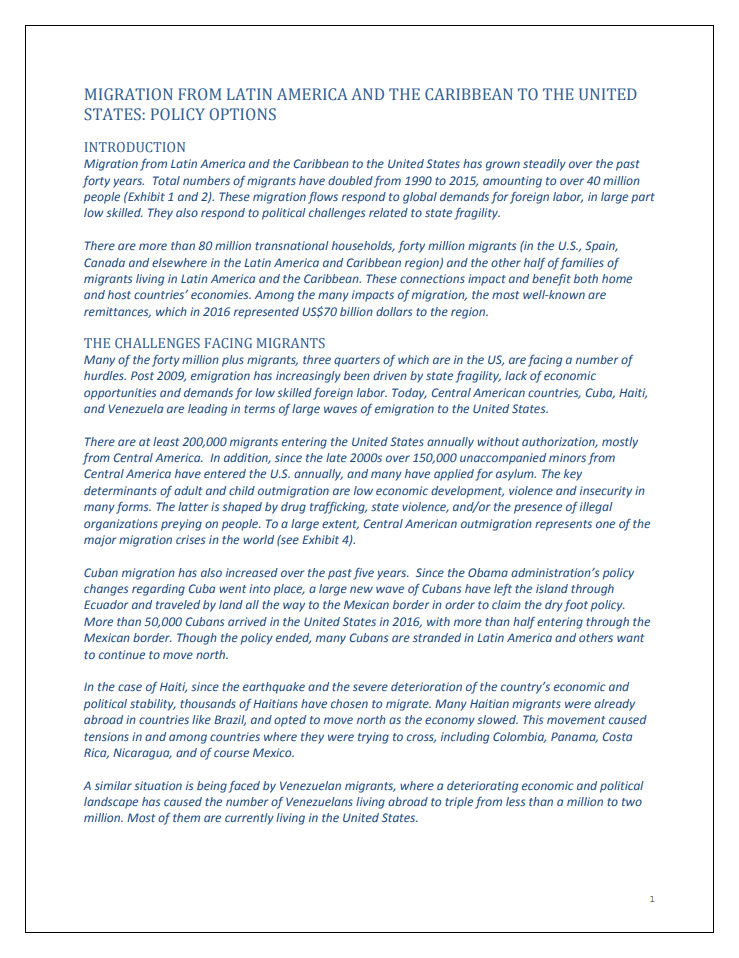

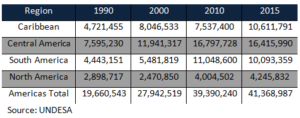

Migration from Latin America and the Caribbean to the United States has grown steadily over the past forty years. Total number of migrants has doubled from 1990 to 2015, amounting to over 40 million people (See Figures 1 and 2). These migration flows respond to global demands for foreign labor, in large part low skilled. They also respond to political challenges related to state fragility.

There are more than 80 million transnational households, forty million migrants (in the U.S., Spain, Canada and elsewhere in the Latin America and Caribbean region) and the other half of families of migrants living in Latin America and the Caribbean. These connections impact and benefit both home and host countries’ economies. Among the many impacts of migration, the most well-known are remittances, which in 2016 represented US$70 billion dollars to the region.

Many of the forty million plus migrants, three quarters of which are in the US, are facing a number of hurdles. Post 2009, emigration has increasingly been driven by state fragility, lack of economic opportunities and demands for low skilled foreign labor. Today, Central American countries, Cuba, Haiti, and Venezuela are leading in terms of large waves of emigration to the United States.

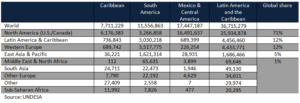

There are at least 200,000 migrants entering the United States annually without authorization, mostly from Central America. In addition, since the late 2000s over 150,000 unaccompanied minors from Central America have entered the U.S. annually, and many have applied for asylum. The key determinants of adult and child outmigration are low economic development, violence and insecurity in many forms. The latter is shaped by drug trafficking, state violence, and/or the presence of illegal organizations preying on people. To a large extent, Central American outmigration represents one of the major migration crises in the world (See Figure 4).

Cuban migration has also increased over the past five years. Since the Obama administration’s policy changes regarding Cuba went into place, a large new wave of Cubans have left the island through Ecuador and traveled by land all the way to the Mexican border in order to claim the dry foot policy. More than 50,000 Cubans arrived in the United States in 2016, with more than half entering through the Mexican border. Though the policy ended, many Cubans are stranded in Latin America and others want to continue to move north.

In the case of Haiti, since the earthquake and the severe deterioration of the country’s economic and political stability, thousands of Haitians have chosen to migrate. Many Haitian migrants were already abroad in countries like Brazil, and opted to move north as the economy slowed. This movement caused tensions in and among countries where they were trying to cross, including Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and of course Mexico.

A similar situation is being faced by Venezuelan migrants, where a deteriorating economic and political landscape has caused the number of Venezuelans living abroad to triple from less than a million to two million. Most of them are currently living in the United States.

In addition to leaving their countries amidst political and economic hardship, the vast majority of these migrants face additional challenges in terms of their legal status in the United States. Some are facing enforcement through apprehensions. Others, who applied for political asylum, are facing denials. The majority are not receiving relief from immigration courts, which are denying applications for asylum.

Overall, migrants are facing legal, economic and social hurdles. Without the possibility of improving their economic situation, achieving legal status or reuniting with their families, their conditions will deteriorate.

Moreover, the Trump administration has promised to build a wall, reduce migration, expedite the return of those applying for asylum, end temporary protected status, and even introduce a tax on remittances.

President Trump’s stance already contains instructions to end asylum relief, authorization to extend deportations not only of criminal aliens, and issued an executive order to withhold federal funds and grants from sanctuary cities. The administration’s messages and policies represent a tougher stance against migration than his predecessors.

This will further reduce the economic benefits of remittances for already fragile states in the region. These realities highlight the need to prioritize legal migration and economic development. The following presents a brief outline for how these goals can be accomplished.

How can the Western Hemisphere address international migration in the current context? Will the Trump administration move towards immigration reform while also tightening its border enforcement approach? Given the uncertain environment, would a deal be possible? What are the long-term effects of this continued migration pattern? Is it possible to implement or expand guest worker programs? Should an approach to skilled labor migration be considered? Can a humanitarian approach to the region’s challenges bring asylum relief to the more than 100,000 minors who currently have applications pending? How can countries strengthen development policies connected to migration?

International migration, mostly to the United States, is central to economic growth and global integration of Latin America and the Caribbean. After all, more than 40 million households with migrants abroad support more than one third of all households in Central America and the Caribbean; and one quarter of many households in South American countries like Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, and more recently, Venezuela. The case of Venezuela has become dramatic in the past few years, with over 2 million Venezuelans living abroad out of a country of 30 million people.

One way to look for solutions is to consider a comprehensive approach to migration through recruitment, retention, return, relief and reform. These are five independent but related strategies to deal with the prevailing challenges of migration. The idea would be to discuss more specifics about policy solutions in this regard.

The debate about immigration reform has predominantly focused on a two tiered context; one, providing a legal path to US citizenship, and two, enforcing migration laws by strengthening the border and reducing employees without authorization to work in the US. President Trump proposed the possibility of immigration reform for the more than 10 million migrants without legal status in the United States. This debate is more relevant than ever, both for the condition of these migrants as well as for the needs of the US economy. Several proposals have come to US Congressional attention. However, the consensus among Democrats and Republicans is to offer a form of legal status to these migrants on the basis of their years in the US, their tax contribution, and paying some form of penalty, among other elements.

To the US Congress what is in question is how many people to legalize and who among those should benefit from such a reform. As a start, the political debate should center along these lines.

The United States and other migrant host countries in Latin America (Argentina, Costa Rica, Chile, Dominican Republic), in Europe (Spain, Italy), and Asia (Japan) show a demand for foreign labor, both high skilled and low skilled. Regarding low skilled labor, guest worker programs or temporary permits can offer important solutions to prevailing challenges.

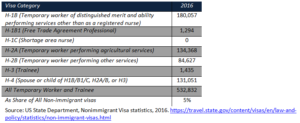

In the U.S. context, temporary worker visas (plus NAFTA visas) amount to less than 6% of all non-immigrant visas. In total, the H visa category amounts to 533,000 visas. (See Figure 5). However, with an annual increase of 0.2% in our labor force of 170 million people, there is a substantive need to replenish labor through migration.

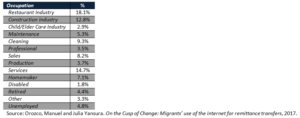

A win-win approach would be to expand H2B visas as a means to address the demand for low skilled labor. Currently most low-skilled migrant workers are already crossing the border without papers, in an insecure and unauthorized manner. About three quarters of undocumented migrants that cross the border from Mexico and Central America work in three predominant occupations: domestic work, construction and hospitality. (See Figure 6). Those workers could benefit from a guest worker program under H2B as a means to realistically integrate them and ease labor pressures in the US market.

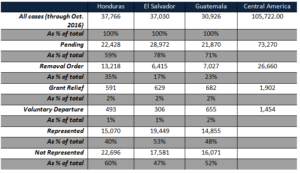

Parallel to labor migration are people escaping regional violence in Central America. In fact, there are more than 100,000 asylum applications from unaccompanied minors coming from Central America alone. Their claims for asylum need a fair hearing and due process. Currently, a large number of these applications are denied; in fact, only 5% are adjudicated for asylum. (See Figure 7)

Many people (over 50%) apply for legal status without legal representation and face immediate deportation once denied. Their claims are coming from some of the most dangerous places in the world where more than 350,000 attempts to enter the US occurred in 2016. The problems asylum seekers face are not limited to due process and lack of legal counsel, but also relate to their social and psychological needs. In order to deal with these issues, it is important to provide greater weight to asylum claims, clarify the claims for asylum, improve the training of judges, improve legal counsel, and provide better information about regional insecurity.

Migration policy includes addressing root causes. In practical terms, it is about retaining the labor force by offering better opportunities at home to those who might otherwise consider migration. It is also about offering a favorable environment to those migrants who return. The approach needs to be different from previous interventions because despite the fact that many development strategies have been implemented to date, they have not yielded the desired result and migration has not gone down. Central America shows the lowest productivity levels in the world largely because its labor force is informal, underpaid, unskilled and uneducated.

A focus on people is essential. It is important to deal with social inclusion, economic transformation, transnational engagement and tackling disruptors as means to increase development. Some tools or methods to do this include:

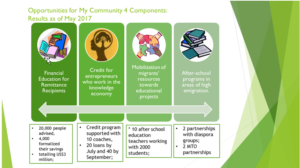

The Dialogue has proposed an innovative strategy for development in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador by integrating migration, remittances, savings and education. The approach links migration and development through five unique and innovative components:

Though independent, these strategies share a common linkage with migration and remittances, complementing one another in terms of asset building. Financial education-and the financial inclusion it provides-is a relevant goal in itself; however, the resources from the financial education program, namely savings stocks, are to be further leveraged in order to promote investment in the knowledge economy. Diaspora demand for home-country products can be leveraged to help promote production of high-quality, specialized exports. Moreover, the diaspora philanthropy can be closely linked to educational services such as the after-school programs for youth in areas of high emigration. The objective is to have a critical mass of people mobilizing savings, investing in education, and contributing to human and economic development as each country transitions to a more knowledge-based economy.

This approach is fundamentally important because it addresses various strategic needs. First, it integrates migrant capital investment and savings from remittances into the financial sector, further mobilizing these resources for local development in education and skill formation. Second, this strategy expands and complements—that is, does not replace—existing approaches to economic growth, and creates a new model for much-needed investments in services for the global economy. Making investments in savings and education as a business strategy will lead to an expansion of opportunities to work and compete in the knowledge economy. In turn, the approach increases resources available and possibilities for greater economic complexity in the region. (See Figure 8).

Moreover, the vast majority of those who return do so through annual deportations nearing one hundred thousand. Those deported are people who have lived more than five years in the US, whose habits and realities have changed and are different to life in the region. The solutions to those returned should be commensurable to their needs.

In summary, we should promote positive outcomes from the challenges, uncertainties, and risks that are currently overshadowing the important contributions that migrants make in the global sphere.

The earthquake in Haiti has exacerbated an existing distress during the international recession and increased uncertainty of what to do and how to help.

President Obama has overseen some of the strictest enforcement policies of the past several decades.

As the global financial crisis continues to alter US relations with the hemisphere, greater engagement in the region remains critical to US interests.