On Lula’s Approach to Asia: Q&A with Karin Costa Vazquez

Insights from Karin Costa Vazquez on Lula’s recent re-election and its significance for Brazil’s relations with its Asian partners and in multilateral institutions.

The five nation Brics group—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—completed an active agenda in Latin America last month. Their sixth summit meeting, hosted by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in the Northeastern city of Fortaleza, demonstrated the substantial progress the group has made in establishing themselves as a genuine bloc or alliance. With the creation of a new international development bank and a reserve arrangement to deal with financial crises, the Brics group could be opening a new chapter in the evolution of global economic institutions, but it will take some years to know if they succeed or not.

Presidents Xi Jinping of China and Vladimir Putin of Russia took advantage of the Fortaleza summit to advance other interests in Latin America. President Xi pursued a particularly broad and ambitious agenda. Granted the honor of a state visit in Brasilia immediately after the summit, he joined President Rousseff in signing a range of agreements that are expected to lead to substantial new Chinese investment in Brazil’s transportation and energy infrastructure and expanded trade between the two nations.

While in Brazil, President Xi also had the opportunity to meet the leadership of CELAC (the 33- member Community of Latin American and Caribbean States), setting the stage for the development of a region wide forum for China’s relations with Latin American and Caribbean. Before returning to Beijing, the Chinese president traveled to Argentina, Venezuela, and Cuba, where discussions again emphasized trade and investment, particularly related to agricultural and energy exports.

In addition to Brazil, President Putin visited Argentina, Cuba, and Nicaragua where he sought to demonstrate, especially to the United States, that Russia remained a relevant political and economic actor in Latin America. His more important objective, however, was to generate what support he could among the Brics and across Latin America for Russia’s actions in Ukraine and opposition to US and European sanctions on his country. At best, he gained only modest ground. The Brics countries mostly sought to avoid confronting the situation in Ukraine. Along with most Latin American countries, the Brics will probably maintain a neutral stance on the question of sanctions, though the downing of the Malaysian commercial airliner by pro-Russian forces in Ukraine could well bring about changes in the attitudes of some countries.

Their advances at the Fortaleza summit notwithstanding, the Brics are not a natural set of partners. They did not come together to defend their neighborhood or to confront a common enemy. They are an accidental alliance, although they do have one vexing challenge in common—how to curb the US and European preponderance of power in international affairs, especially on economic matters, and expand their own.

Aside from their relations with China, the Brics’ economic ties with each other are modest. China is a sizable trade partner for every other Brics nation, accounting for an average of 15 percent of their foreign trade. However, taken together, the other Brics comprise less than 10 percent of China’s trade, and they hardly trade at all among themselves. None of them is counted among China’s five main trading associates. While the economic weight of the Brics as a group is impressive, the heft comes mostly comes from China—including two thirds of the group’s total economic output and 90 percent of its reserves.

The Brics were initially identified in 2001 by a far-sighted investment banker, Jim O’Neill. He urged investors to turn more attention to the world’s emerging markets, and pointed to Brazil, Russia, India, and China as four of the most potent of those markets. He saw them as rapidly growing competitors with the traditional economic giants of the United States, Europe, and Japan.

With their gargantuan populations and rapidly expanding economies, China and India were obvious candidates for this top tier group of developing countries. Russia and Brazil were not. As the Soviet Union, the new Russia Federation had once shared super-power status with the United States, but by the turn of the century, it was only beginning to recover from virtual economic collapse and show its potential as a "re-emerging” market.

Although it had finally tamed its greatest adversary, runaway inflation, the Brazilian economy was still stumbling along badly at the turn of the century. It was included in the Brics because it was the giant of Latin America, though at the time Mexico was a strong candidate as well. If it had been included, the Brics today might have a less left leaning, anti-US tinge. South Africa was not among O’Neill’s initial group, but was invited by the others to join in 2010, thereby including an African nation and making the Brics more representative of the Global South.

An initial gathering of the Brics was held New York in 2006, when the foreign ministers of the four charter members met during the UN General Assembly. The group shared little in common except a general dissatisfaction with the continuing constraints on their influence in global affairs, and a joint interest in expanding their ability to shape the agenda and key decisions in of the major multinational institutions.

The first Brics summit took place in 2009, when the four heads of state of assembled in Russia. The group’s concerns about international decision-making had grown more urgent and its demands for change were increasingly insistent. In part, the new assertiveness reflected the impressive economic performance of each of the four Brics and their growing international voice. But more important still was the devastating impact of the 2008/2009 worldwide financial crisis—principally caused by the economic and financial failures of the United States and the European Union. Although unartfully, then Brazilian President Lula da Silva famously pointed to “white people with blue eyes” as the culprits.

For their part, the US and EU responded slowly and begrudgingly to the increasing demands of the developing nations for a larger role in managing the world’s financial affairs. They agreed to replace the long established G-8 group of leading industrialized countries (which included only one Bric nation, Russia), with a more globally representative arrangement for coordinating international financial affairs. The new G-20 group incorporated all the participants of both the G-8 and the Brics, plus another ten or so emerging economies. But the G-20 was mostly a place to exchange information and hear first hand about national policy decisions. In practice, it had little on influence on critical national or global economic policies.

Long discussed reforms of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank seemed more likely in the aftermath of the crisis, and there was some expectation that the US and the EU would allow an open competition for the leadership of these two Bretton Woods organizations. Yet, despite strong candidates from the developing world, the two positions were filled according to long-standing practice. One went to an EU citizen and the other to an American. Former French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde was elected managing director of the IMF in 2011 and the president of Dartmouth University, Jim Yong Kim, a US citizen, became president of the World Bank in 2012. Moreover, the US Congress failed even to approve a small number of reforms endorsed by the Obama Administration and the IMF Board of Governors in 2010. If enacted, the reforms would have modestly expanded the voting shares of developing nations to acknowledge their rising economic importance in world affairs.

Their multiple differences aside, the five leaders of the Brics group—host Dilma Rousseff, Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, Jacob Zuma of South Africa, and newly-elected Narendra Modi of India—agreed on one central purpose for their meeting in Fortaleza. They were intent on building an institutional basis, beyond their annual meeting, for a continuing, coordinated effort to increase their influence on world economic affairs. And they succeeded in establishing two new financial institutions—a development bank, called the New Development Bank, which would largely focus on infrastructure needs and a contingency arrangement to serve as source of liquidity support in times of crisis. From the start, the two institutions will be reasonably well funded, although not yet approaching the levels of the Bretton Woods organizations. The bank will start off with a $50 billion commitment from its five members, and a near-term objective of building toward a $100 billion capital base, while the contingency fund will start with $100 billion.

It should escape no one that the new bank and contingency fund are intended to perform functions similar to those of the World Bank and the IMF. A well-worn English maxim of the 19th century claims that “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. “ And, with their new institutions, the Brics are showing their regard for the functions performed by the Bretton Woods forerunners. The IMF managing director has publicly and justifiably applauded the Brics’ creation and the note the important contribution they can make. But they are not intended merely to mimic the Bank and Fund or simply add a new source of needed lending. What the Brics governments have in mind are institutions that will chart the way for new ideas and approaches to international development and finance.

How the Brics institutions actually perform and develop over time depends on myriad details that are yet to be worked out, including prominently the managers and specialists who are recruited to oversee and run the operations. It is widely expected that it will take at leas two years, and perhaps more, before the institutions will be ready to begin lending.

A few things are clear, however. By retaining a minimum of 55 percent of voting shares (more that the US and Europe currently hold in the IMF and World Bank), the Brics members plan to maintain control over the management and operations of the new institutions into the future. And the first beneficiaries will be the Brics countries themselves. Although the intention is for the new bank and contingency fund to eventually serve a wider group of emerging market nations, how governments apply and what lending criteria have to be met have not been decided.

Brics officials have consistently objected to the multiple layers of conditionality that are prominent features of World Bank and IMF loans, and will almost certainly make the lending conditions of the new institutions far less demanding. For sure, they will be less intrusive into matters of national governance. Environmental protection, political and judicial reform, social inclusivity, transparency, and human rights concerns will all get less attention.

Finally, the Brics will not be fully satisfied merely to run their own institutions. They will continue to press for an expanded role in managing and shaping the policies of the traditional multilateral organizations.

An important unanswered question is whether the new institutions will retain some autonomy from the Brics governments and be able to operate independently of them. Or will its independence be constrained by the continuing involvement of the Brics partners in the governance and operations of the new organizations? The discussions in Fortaleza suggested national interests would play a central role in the Bank’s decision. The choice of Shanghai—rather than New Delhi or Brasilia—as the Bank’s headquarters mostly reflected China dominant position among the Brics. In exchange, India was granted the right to name the first president, while Brazil will select the chair of its board of governors. Russia gets to choose the chair of an executive committee, and South Africa has been granted a regional office. It is unclear how the Bank’s development will be affected by the decision that each Brics nation contribute equally ($10 billion, initially) to the capital base and gain an equal voting share. By rejecting China’s offer to contribute a greater amount in exchange for a greater number of shares, the other Brics have limited the Bank’s capital, at least for the time.

A related challenge for the Bank and the reserve arrangement is whether the two institutions will, in effect, be dominated by China and viewed internationally as mostly a Chinese lender—or will they be able to operate as genuine multilateral institution. The Bank’s location in Shanghai will clear identify it closely with China. Moreover, any effort to expand the new Bank in the coming period is likely to depend on contributions from China since its resources are so much larger than those of any other Brics nation.

What should be emphasized at this stage is that neither the New Development Bank nor the contingency arrangement represents a threat to the World Bank or IMF—and are certainly not going to replace them. It will take many years for the new institutions to gain the authority and legitimacy of the Bretton Woods system, and to build up sufficient capital to emerge as rivals or competitors. Most countries of the world will prefer to have both sets of institutions operating.

The ideal outcome of the Brics initiative will be, over time, to firmly establish two new large global lenders that are well endowed, intelligently managed, and highly creative and that can serve as both as complements and rivals to Bretton Woods. Success of that magnitude would assist the Brics achieve their goals of greater influence and potency in world affairs, collectively and individually.

But regardless of the success of the group’s new institutions, the Brics’ future role in the global economy and international relations will depend mostly on the performance of their own economies and governing institutions, and the extent to which they are able to satisfy the needs of their citizens.

Insights from Karin Costa Vazquez on Lula’s recent re-election and its significance for Brazil’s relations with its Asian partners and in multilateral institutions.

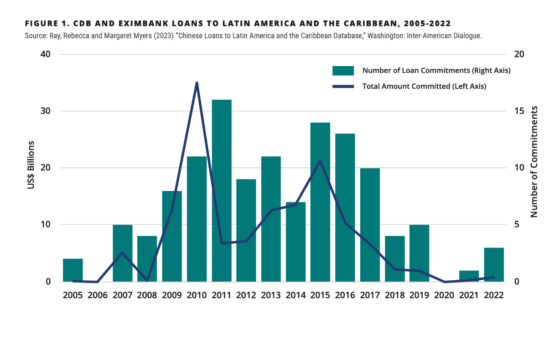

In the newest episode of The China-Global South Project Podcast, Margaret Myers, director of the Asia and Latin America Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, considered new trends in Chinese economic engagement with the LAC region.

Testimony by Program Director Margaret Myers to the Senate Finance Committee on Economic Cooperation for a Stronger and More Resilient Western Hemisphere.

Kremlin / CC BY 3.0

Kremlin / CC BY 3.0

Video

Video