Latin America Advisor

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

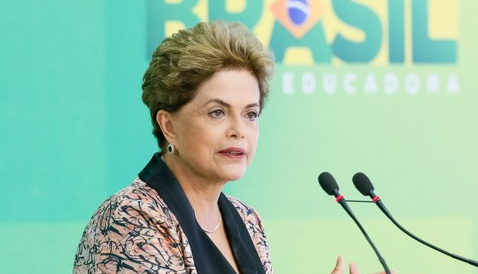

Is the Rousseff Era Coming to an End in Brazil?

In a pivotal vote Sunday, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff moved a step closer to being ousted as her opponents in the lower house of Congress easily surpassed the two-thirds majority needed to move her impeachment to the Senate, which needs only a simple majority vote to put her on trial and possibly remove her from office. Will Rousseff lose the presidency? If so, what will happen next? To what extent is the debate over Rousseff’s impeachment about her alleged mishandling of government accounts, an accusation she denies, or is it mainly about her management of the economy and the Petrobras scandal, in which she has not been charged directly? What will be the long-term consequences of the impeachment process on her Workers’ Party and on Brazil’s democracy?

Peter Hakim, member of the Advisor board and president emeritus of the Inter-American Dialogue: "President Rousseff’s impeachment is welcomed by most Brazilians, who have concluded their government has, for the past three or four years, been highly dysfunctional and deeply corrupt, incapable of grappling with the country’s economic trauma and most other systemic problems. Brazilians also know that not just the government, but virtually the entire political system is at fault—aside from the judiciary, which has exposed the public and private corruption plaguing Brazil and is actively prosecuting those responsible. While 60 percent of the population wants Dilma’s presidency to end, the same number supports the ouster of Vice President Michel Temer, who will likely soon be president for three to six months while the Senate decides whether Dilma should be removed. One question is whether Temer, who is not particularly known for dynamic leadership, can assemble a large enough share of Brazil’s 32 political parties to form the national unity government he has proposed. His most critical test will be whether his government is able to design and gain support for an economic program that can begin to halt economic decline and restore growth. Not an easy task during a period when the continuing impeachment battle and corruption scandals will be absorbing most political attention. Temer should also consider seeking a constitutional amendment allowing for the immediate election of a new president and vice president, should the curtain fall on Dilma’s presidency. An elected president would have far greater credibility than Temer, and could well bolster his authority as acting president. A final point: Dilma’s impeachment is not a coup d’etat. True, the charges against her are a weak basis for removal, but Brazil’s Supreme Court has found them to be valid and has been closely monitoring and supervising the entire process, which has met constitutional requirements. Impeachment is not just a judicial process; it is also a political undertaking."

Gilberto M. A. Rodrigues, professor of international relations at the Federal University of ABC and member of the Coordinadora Regional de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales: "The decision by the lower chamber to begin an impeachment process against President Rousseff makes no sense from a legal perspective and, at the same time, is an immoral political maneuvering to end Rousseff’s mandate, aiming to revert the country’s political and economic crisis. Actually, she has committed no crime. At one point, the acts she committed were allowed by the Federal Account Court and have been committed by her predecessors. The fact that the president of the lower chamber, who is publicly an enemy of the president, has been formally accused of many crimes, brings an air of suspicion upon the whole process in which he acted as a ‘judge.’ There is an expectation now, at least from part of the public opinion and the legal community, that the process in the Senate will be more rational and constitutional and less passionate and political than had been the case in the lower house. In fact, article 54 of the Constitution says that the Senate has the exclusive right ‘to effect the legal proceeding and trial of the president and vice president of the republic for crime of malversation.’ The Supreme Court may also play a role in controlling that process. Moreover, the expectation of a new and better government under an ambitious vice president, who has low support from the public, is a very risky bet, yet most of the politicians opposed to President Rousseff are threatened by the ‘Car Wash’ judicial task force and could go to jail. Thus, Brazil’s future will depend on the extent to which its democracy is hurt by the troubling regime change."

Mark S. Langevin, director of BrazilWorks and adjunct professor at the Brazil Initiative of the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University: "The vote to impeach President Dilma Rousseff is an important chapter in a political struggle to remove the Workers’ Party from the presidential palace. The president’s party has not lost a presidential election since 1998, but Dilma barely won re-election in 2014, only to lose popular support amid economic decline and the cascading revelations of corruption discovered by the ‘Operation Car Wash’ corruption probe. The impeachment process will likely be successful and complete an historic mutiny plotted by Vice President Michel Temer and the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha, both of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB). The PMDB has always been the cornerstone of governability under Brazilian democracy, and this latest move ensures its continued role until at least the next presidential election in 2018, but not without casting a shadow of illegitimacy over the impeachment proceedings. The impeachment vote was a devastating political defeat for the Workers’ Party, but the process may also lead to greater scrutiny over Temer’s role in corruption. More than one deputy voting for the impeachment also called for the heads of Temer and Cunha. Under a Temer provisional administration, the PMDB will forge a partnership with the arch rival of the Workers’ Party, the Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB) led by Senator Aécio Neves, who finished a close second place to Dilma in 2014. The Progressive Party, a former ally of Dilma, is also part of this mutiny and will join in Temer’s governing alliance with the PMDB and PSDB along with other smaller parties. This party has the most members convicted by the Operation Car Wash task force to date. Temer and Neves are both under suspicion for corruption related to the Petrobras kickback scandal. Eduardo Cunha (and possibly his wife) could face criminal charges for allegedly receiving millions of dollars paid by Petrobras contractors and stashed away in Swiss bank accounts. Dilma is all but gone, but it is too early for Temer’s mutiny to declare victory."

Maria Velez de Berliner, president of Latin Intelligence Corporation: "Unless she resigns for ‘the good of the country,’ Brazil’s Senate will impeach Rousseff. In either case, she and Lula’s PT decade will officially end, to be replaced by an equally discredited interim chief executive or political coalition. Rousseff’s impeachment for her alleged ‘knowingly manipulating national accounts for political gain,’ as previous, non-impeached presidents did, is no longer the point. The central issue is that this is an institutional coup, led by officials who themselves are under investigation for money laundering, corruption, collusion, extortion, influence peddling and sundry unlawful transgressions. That Rousseff, a technocrat by training and experience, was politically inept in handling the perfect storm of Petrobras’ corruption scandal, a decline in Chinese demand for Brazil’s commodity exports, global economic stagnation, the consequent unemployment and dashed expectations of continued growth and the machinations of adept operatives, seasoned in the blood sport of Brazilian politics, cannot be denied. However, those who are celebrating should acknowledge theirs is a pyrrhic victory with Brazilian institutions and electorate as the ultimate losers. The circus atmosphere at the Chamber of Deputies as votes, pro or con, were cast on Sunday displayed for the world to see how low Brazil’s political leadership has fallen. This added to the profound and deserved dissatisfaction and contempt Brazilians are expressing toward their leaders in government and private industry. Regretfully, only some of the same lies in the horizon as a replacement. What Brazil needs is not an interim, under-suspicion chief executive instead of Rousseff. The need is for profound and long-lasting cultural change that establishes credibility in Brazil’s government, its institutions and public and private leadership across the board. Given the country’s governance and political history, it will be a long time in coming, if at all."

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.