Protecting Latin America’s Poor During Economic Crises

History tells us that economic crises cause large increases in poverty. The most recent economic crisis will cause Latin America’s GDP to contract around 2 percent in 2009.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Prior to the pandemic, children from the wealthiest households in 21 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean were five times more likely to complete upper secondary school than those from the poorest households in those same countries, and Covid-19 exacerbated these inequalities, according to the most recent Global Education Monitoring Report published by UNESCO. What are the most significant implications of the growing education gap in Latin America and the Caribbean? To what extent has the pandemic reversed progress made in education in the last decades and heightened inequalities? In the years ahead, what should countries focus on in order to better rebuild the region’s education systems and to guarantee a more equal access and quality learning for all children?

Nora Lustig, Samuel Z. Stone professor of Latin American economics and founding director of the Commitment to Equity Institute at Tulane University and nonresident senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue: “Education may be Latin America’s most lasting scar from Covid-19. Our research suggests that the likelihood of today’s students to complete secondary education may soon drop from a regional average of 61 percent to 46 percent. This average, however, hides striking differences across socioeconomic groups. While schools shut their doors for children of all backgrounds, their ability to continue learning depends on their parents’ income and educational level. Children in low parental education households find it difficult if not impossible to continue their education at home due to a lack of adequate equipment, connectivity and—above all—one-on-one coaching. The probability of completing secondary school for these children could fall by almost 20 percentage points, from 52 percent to 32 percent. This low level of educational attainment for children of disadvantaged families was last reported for cohorts born in the 1960s (!). In contrast, children from highly educated families are hardly affected. The growing educational gap will cause devastating damage to social mobility and equality of opportunity for years to come unless we take the warning signs seriously and act fast. There will be a need to make up for the losses by increasing both the amount and quality of learning time. School systems will need to contemplate extended schedules, summer and after-school programs, and more personalized instruction. Efforts should also be geared to developing online and offline resources available for free and expanding connectivity. Governments should avoid cutting education spending when they face the inevitable need to rein in fiscal deficits. In fact, if anything, fiscal resources devoted to education may need to rise.”

Leonardo Garnier, former education minister of Costa Rica: “In recent decades, Costa Rica has managed to significantly increase high school enrollment, reducing both urban/rural and high/low income educational gaps. However, as in many Latin American countries, the impact of the pandemic could reverse such advances, especially for those students from rural areas, where Internet connectivity is lowest, and for those whose families have been hit hardest by the pandemic. As in-person classes had to be suspended for all of 2020, the Ministry of Education had to resort to a combination of distance-learning instruments, including virtual classes via the Internet, televised lessons, telephone and chat communications. At the same time, a strategy was developed to guide both teachers and students as to how best to achieve and evaluate the priority learning objectives that were established. There is no doubt that this is not an ideal situation, and it will have a negative and unequal impact on our education. However, at the same time, the crisis might work as an opportunity and as a catalyst for change. It has become obvious that a combination of pedagogical and technological tools were already available to promote learning, even in the most distant or disadvantaged regions of the country, and to offer real learning options to those students who most need it. The crisis could accelerate national efforts to fully implement such reforms and to guarantee improved access to education both through effective connectivity and adequate teacher training on how to best use these resources.”

Sarah Stanton, senior associate in the Education Program of the Inter-American Dialogue: “Although governments in Latin America and the Caribbean should be commended for their efforts to ensure learning continuity since March, when more than 165 million students stopped attending in-person classes, the education landscape was already marked by inequality. We do not yet have a full picture of the impact of school closures and remote instruction on student learning outcomes, but emerging data show widespread learning losses, most acutely for students who are poor, marginalized or otherwise vulnerable. Projections from the World Bank suggest that seven months of school closures—a benchmark that most countries have already passed—could result in a year of learning loss and, longer-term, up to $1.2 trillion in foregone earnings. This trend is unsurprising given the significant regional connectivity gaps and the resulting struggle to keep students engaged and learning. To prevent compounding these inequalities, governments should target those most at risk, first, to meet basic connectivity and access needs, and in the longer term, through policies expanding access to quality teachers and adequate resources. Students at either end of the formal schooling spectrum may well be the most affected by this pandemic. Early grades are critical for building foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Many secondary students face a combination of sustained time away from school and economic pressures to contribute to family income, which may thwart their return to the classroom. To address these challenges, education ministries should set and communicate priorities emphasizing foundational knowledge and skills, so that teachers have clear curricular guidelines and student outcomes are protected.”

Debra Gittler and Zoila Recinos, co-founders of ConTextos in El Salvador: “As the more affluent continue to advance in their schooling, the impoverished have become ever more marginalized. We have seen reversals in areas where we were seeing progress, namely school abandonment and desertion, returning to traditional patriarchal roles in home and community, physical and emotional violence and ongoing trauma. Without school, our youth are returning to ‘traditional’ roles, especially through girls tending home and family and boys’ hypermasculinization. This is coupled with increased anxiety as well as abuse and assault, which will have devastating long-term impacts that are not easily resolved. We’ve seen potential in solutions that are hyper-local—smaller organizations with community roots are able to step in, build trust and foster real grassroots solutions that go beyond ‘schooling’ to finally make strides away from the copying, dictation and memorization methods that have been so hard to dispel. This is an opportunity to widen our circle of wise teachers, to engage children and youth in learning beyond the traditional canon, and to integrate technology in new ways. With ConTextos, teachers have been meeting regularly via small digital learning pods and ubiquitous technologies such as WhatsApp. Transforming how teachers learn will have an immediate influence on how they teach. We can amplify professional development networks, while going hyper-local for educational innovation and using technology to create cross-border affinity groups. Perhaps the most exciting opportunity is to finally integrate trauma-sensitive programming, to rebuild our curriculum to emphasize socioemotional and socioaffective communication, and address generational cycles of trauma and disenfranchisement.”

Mary Guinn Delaney, regional advisor for Health and Well-Being at UNESCO’S Regional Office for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean in Santiago, Chile: “UNESCO’s recent regional Global Education Monitoring report highlights the many inequalities that have persisted in the region for decades and describes challenges to education systems as they seek to address the historic exclusion of children living in rural areas and those living with disability, among other groups. Socioeconomic level is another important predictor for disengagement from education and eventual desertion, and it has been an important determinant in the widening of existing gaps during the pandemic. Prior to Covid-19, major progress had been made in many countries in the region to ensure educational continuity through secondary levels as well as broader access to pre-school education. These gains are now threatened by the digital divide that keeps millions of students from effectively accessing online learning and maintaining vital contact with their teachers and classmates. School closures have also dramatically reduced access to other basic services upon which many vulnerable children, young people and families depend: school feeding programs, social protection services, practical training opportunities required for some fields of study and basic health interventions such as vaccinations, well-child checkups and dental care. While we must recognize the major efforts of millions of teachers all over the region to protect their students and their educational trajectories, it is clear that distance education and the ‘hybrid’ model being adopted in many contexts are not reaching all who need support. The gradual return to the classroom makes it imperative for education systems to identify and prioritize those students most affected in academic, socioemotional and socioeconomic terms. Before the pandemic we already knew a great deal about these groups and the dynamics of systematic exclusion—now is the time to move beyond description and put in place programs that prioritize and respond to their needs.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

History tells us that economic crises cause large increases in poverty. The most recent economic crisis will cause Latin America’s GDP to contract around 2 percent in 2009.

The goal of education is to promote learning. Sitting in classrooms is a weak proxy for knowing how to read, do math, and apply science. Latin America needs to worry less about schooling and more about learning.

The mobilization of 70,000 students in the streets of Chile is more than just a protest for free higher education.

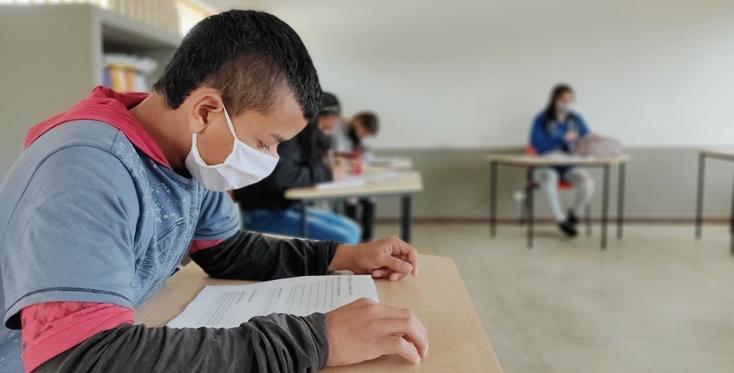

The Covid-19 pandemic has worsened inequalities in education in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to a United Nations report. // File Photo: Colombian Government.

The Covid-19 pandemic has worsened inequalities in education in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to a United Nations report. // File Photo: Colombian Government.