Rising Brazil: The Choices Of A New Global Power

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

Brazil is on track to double its oil and gas production following a series of energy policy reforms aimed at increasing investment, according to a panel at the Inter-American Dialogue. On May 5, the Dialogue welcomed Decio Oddone, general director of the Brazilian National Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels Agency (ANP), Jorge Camargo, president of the Brazilian Petroleum, Gas and Biofuels Institute (IBP) and Jed Bailey, managing partner at Energy Narrative and editor of The Weekly Brief: U.S. Global Impact to discuss the far-reaching implications of these changes.

Brazil holds massive oil and gas reserves. But oil output has grown much slower than anticipated as state oil company Petrobras failed to meet its production targets and investment from international companies was restricted by nationalist oil policies introduced in 2010 under President Lula.

The administration of Michel Temer – who took office last year after the impeachment of his predecessor Dilma Rousseff – has taken a more market-oriented approach, working to jump-start private investment in the sector. Last year, President Temer signed legislation ending Petrobras’ monopoly on pre-salt operatorship. In February, the government also announced it would halve local content requirements for the oil industry to lower operating costs and make it easier to hire international contractors. Additionally, the government approved a calendar of oil licensing rounds for the first time since the first pre-salt discovery was announced in 2007. The first calendar covers 2017-2019, but going forward, the ANP hopes to move to a five-year calendar. Temer also appointed Pedro Parente as CEO of Petrobras with a mandate to oversee Petrobras’ financial recovery. In the past two years, Petrobras has sold almost $14 billion in assets, and the company is looking to sell another $21 billion by the end of next year.

The changes in the oil and gas sector go beyond just upstream exploration and production. Petrobras’ massive divestment plan is creating opportunities in refining and in the natural gas business (including infrastructure and logistics assets), which have not seen any relevant private sector presence due to Petrobras’ dominant role, said Oddone.

However, there are still two very important sticking points that must be addressed – regulatory and tax stability and environmental licensing – according to the IBP. The government has promised to extend a benefit that would remove taxes from oil sector investment in the coming days, without which Brazil will not be able to compete in the current global scenario, said Camargo. He stressed that the backlog in granting environmental licenses is perhaps the most significant obstacle to investment. In a 2013 bid round, companies committed to drill 37 wells which have still not received an environmental license four years later, noted Camargo. In an effort to address this bottleneck, Congress is discussing establishing firm schedules that dictate a timeline for environmental agencies to make decisions about environmental licenses.

However, there are still two very important sticking points that must be addressed – regulatory and tax stability and environmental licensing – according to the IBP. The government has promised to extend a benefit that would remove taxes from oil sector investment in the coming days, without which Brazil will not be able to compete in the current global scenario, said Camargo. He stressed that the backlog in granting environmental licenses is perhaps the most significant obstacle to investment. In a 2013 bid round, companies committed to drill 37 wells which have still not received an environmental license four years later, noted Camargo. In an effort to address this bottleneck, Congress is discussing establishing firm schedules that dictate a timeline for environmental agencies to make decisions about environmental licenses.

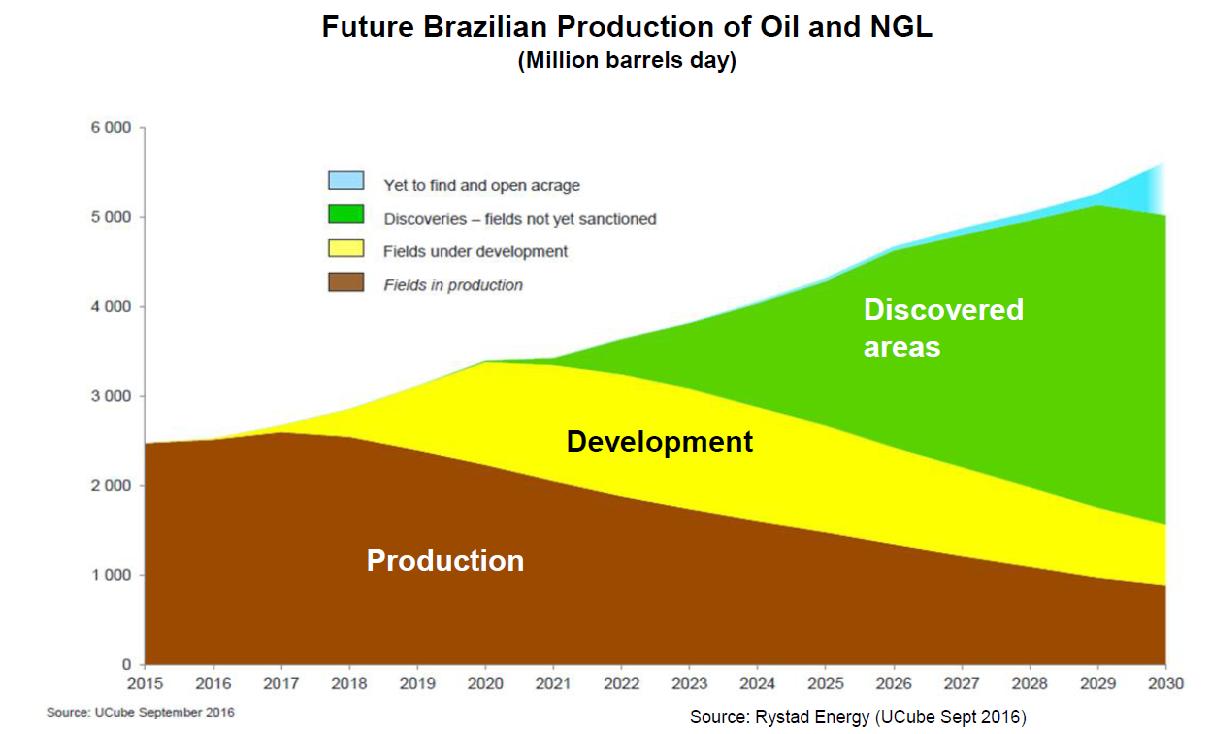

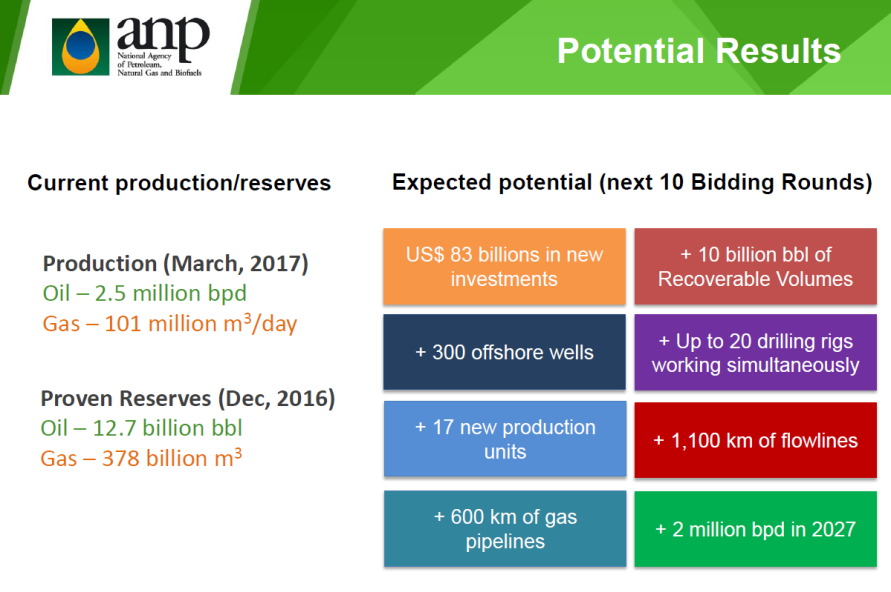

Brazil has the capability to double its oil and gas production in the next 15 years if it removes these obstacles, noted Camargo. Oddone echoed this projection, forecasting up to $83 billion in investment in the next ten bid rounds and a 2 billion barrel per day (b/d) production increase by 2027. Even in a $40-60 price environment, Brazil’s offshore pre-salt wells are extremely competitive because of their high productivity, explained Camargo. Pre-salt wells produce an average of 20-30 thousand b/d of oil, and some reach as high as 40 thousand b/d. By comparison, wells in the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico produce an average of 15 thousand b/d and 10 thousand b/d, respectively.

As Brazil increases oil production, it will also need to make use of the associated gas produced at its wells. The world is awash in natural gas, much of it produced at no cost as a byproduct of shale oil production in the US, explained Bailey. In this respect, Brazil is in many ways in an enviable position, he noted, as its sizable domestic economy can absorb large amounts of gas. In today’s market, it has become increasingly difficult to export excess volumes. These trends are further complicated by a surge in renewable energy investment and dramatically falling costs of solar power in Latin America. Gas will still be needed as a secure source of base load power, noted Bailey, but the volume required will decrease and become far more volatile, creating a challenge for oil and gas producers, especially in countries with less domestic capacity to absorb gas.

As Brazil increases oil production, it will also need to make use of the associated gas produced at its wells. The world is awash in natural gas, much of it produced at no cost as a byproduct of shale oil production in the US, explained Bailey. In this respect, Brazil is in many ways in an enviable position, he noted, as its sizable domestic economy can absorb large amounts of gas. In today’s market, it has become increasingly difficult to export excess volumes. These trends are further complicated by a surge in renewable energy investment and dramatically falling costs of solar power in Latin America. Gas will still be needed as a secure source of base load power, noted Bailey, but the volume required will decrease and become far more volatile, creating a challenge for oil and gas producers, especially in countries with less domestic capacity to absorb gas.

Looking ahead, Camargo highlighted three events to watch that will have important implications for the sector: the 2017 bid rounds, Petrobras’ divestments and Brazil’s 2018 presidential elections. This year’s bid rounds will indicate how successful the Temer administration has been in its attempt to attract upstream investment. Petrobras’ divestment plan also has wide-reaching consequences, as it affects not only Petrobras’ shares and financial recovery but also the opening of the sector, as new opportunities for private sector investment are made available. Presidential elections will affect the investment climate as well, noted Camargo, but their impact will be greater on services companies, which make shorter-term business decisions, than for upstream oil and gas investments, which have a multi-decade horizon.

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH |

SPONSORED BY |

|

|

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

President Lula da Silva triumphantly announced that he and his Turkish counterpart had persuaded Iran to shift a major part of its uranium enrichment program overseas—an objective that had previously eluded the US and other world powers. Washington, however, was not applauding.

Brazil’s rising stature and influence will be on display when President Dilma Rousseff arrives in Washington this week.