Venezuela Needs Its Neighbors

Events in the Ukraine have lifted the morale of anti-government protestors in Venezuela and elevated their expectations.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Colombian President Gustavo Petro on Feb. 13 presented a set of controversial social and economic reforms to Congress focused on the health care sector. The government said the changes would protect workers’ rights, improve primary care, expand access to treatment, raise health care workers’ salaries and address corruption by eliminating private sector management of payments. On Feb. 14, thousands took to the streets in support of the reforms, while the next day, opposition-led demonstrators protested against them. What is the current state of Colombia’s health care system, and what specific reforms would do most to improve it? How would the proposed health care reforms address the issues the Petro administration outlined, and why are they controversial?

Anwar Rodríguez Chehade, deputy director of ANIF-Centro de Estudios Económicos: “The current Colombian health system is probably the biggest achievement in social equity over the last 30 years. Before its creation in 1993, health coverage reached less than 25 percent of the population. Moreover, just 4 percent of the population with lower income was insured. In addition, resources were insufficient and badly managed; a good part of the money was lost in corruption. Public hospitals, for example, were not able to fully function year round. Before, health was a privilege for people with enough money to pay for it, while it was delivered almost out of pity to the most vulnerable ones. Today, the current insurance system has nearly universal coverage (99 percent), above regional pairs like Chile (93.4 percent), Mexico (88.3 percent) and Costa Rica (91.6 percent), and it provides financial protection against disease for all households. At the beginning of the 1990s, a Colombian had to pay out 50 percent of the total cost of their health expenses out of pocket, while nowadays it is merely 14.9 percent, one of the lowest out-of-pocket figures, not only compared with other countries in Latin America but also with those in the OECD. Finally, in terms of quality, more than 80 percent of Colombians evaluate the system as good or very good, and most importantly, there is no distinction of the satisfaction levels controlling for income. In this context, it is worrisome—to say the least—that the backdrop of the health care reform proposed by Petro’s administration will take us 30 years into the past. We should be past ideology and look forward to solving actual problems in our health system, such as having better results on treatment of communicable and noncommunicable diseases, providing care and access in rural and remote areas and providing better conditions for health workers. The government’s proposals are not new, and most of them have already proven to be wrong in the past. Why would they work now?”

Maria Velez de Berliner, chief strategy officer at RTG-Red Team Group Inc.: “Colombia’s health care system is neither fair, equitable nor accessible to every Colombian. But it is neither broken nor in need of being trashed. The proposed health care law, now before Congress, aims to destroy what works, albeit with flaws that need correction. The new law promises improvements and expansions it cannot deliver due to a lack of funds and its cumbersome organization in which communities, mayors and governors would decide who receives care and of what type, all determined by so-called community needs and standards. No wonder even the president of the Senate, Roy Barreras, is against the proposed health care norms and regulations. Given widespread political, social, financial and cultural opposition to the new law, it is unlikely that Congress will approve it. However, the door to health reform is open. Through it must pass four necessary reforms and expansions to the existing system: 1.) Bring health care to unserved, or poorly served, rural areas. 2.) Bring the five Entidades Promotoras de Salud (EPSs), now in default, under one umbrella EPS financed by the government but managed by a successful EPS such as Suramericana. 3.) Finance preventive rather than curative medicine. 4.) Do not go back to the old social security system, which turned into a financial and medical disaster for lack of timely medical attention, long waiting lines, poorly paid or outright incompetent staff and massive, public waste.”

Javier Guzman, director of global health policy and senior fellow at the Center for Global Development: “In 1993, Colombia embarked on a major health sector reform, introducing mandatory universal social health insurance. Since then, the country has made remarkable progress toward universal health coverage, financial risk protection and access, regardless of ability to pay. Coverage increased from 23.5 percent of the population in 1993 to 99 percent in 2022, out-of-pocket expenditures fell from 52 percent in 1993 to around 15 percent in 2019 and all citizens within the system are entitled to an equal basket of services. In 2016, an independent OECD review stated that ‘Colombia offers a remarkable example of rapid progress toward universal health coverage that deserves to be better known internationally.’ Despite these impressive achievements, the Colombian health system faces important challenges—financial sustainability, regional and urban-rural inequities and an imbalance between primary and specialized care. Insurers, which are mostly private, often don’t manage clinical and financial risk appropriately, and poor employment contracts, inefficient payment systems and a lack of infrastructures in some areas hamper quality of care, especially at the primary care level. The Petro reform attempts to solve these problems by moving to a quasi-National Health System focused on prevention and primary care. Central and subnational governments, rather than insurers, would be responsible for purchasing and providing health care, health care workers would have a special work regimen and the public health infrastructure would be strengthened. The reform is controversial because it breaks from the system the country has built over 30 years and some have said that the government is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. It would be better to strengthen the regulation of insurers, provide incentives to reward prevention and quality of care and consider an alternative model to remote and disperse areas.”

Carolina Batista, head of Global Health Affairs at Baraka Impact Finance and incoming member of the Movement Health 2030 Board: “Despite the Colombian health system’s achievements in recent decades toward universal health insurance coverage, important challenges persist. The country’s health system has long been recognized as fragmented, with limited investments in primary health care and suboptimal infrastructure. The system strains to cope with the increasing needs of Colombia’s aging population, a steep rise in chronic, noncommunicable diseases, persistence of infectious diseases linked to poor sanitation and inadequate distribution of the health work force to deal with the pressing needs of Indigenous and other vulnerable groups. With this in mind, there is a need to transform health care in the country. This would require increased public health spending, primary care strengthening, scaling up early screening and detection to shift focus from curative to preventive approaches and improving funding allocation to address challenges such as the growing demand for long-term care and implementation of health technology. An appropriate combination of technology adoption and innovation is necessary to develop new care models. The reform that President Petro has proposed aims to strengthen preventive care, guarantee the traceability of financial resources and improve human talent. There is support for these objectives, but significant challenges are anticipated concerning its implementation. There are questions about how it will effectively improve access to and quality of health services, how it will successfully enable and scale digital transformation and its potential impact on the complex logistics and supply chain of pharmaceutical products, especially in hard-to-reach areas. Overall, despite agreement on the need for reform, experts say it should not be done without an in-depth analysis of current challenges, relying on various sectors, both public and private, with defined milestones and transparency, and ideally with social participation from vulnerable and underrepresented groups to ensure co-ownership and relevance.”

Alessandra Durstine, CEO and founder of Catalyst Consulting Group LLC: “A populist commitment to serving the poor is considered a slam dunk in Latin America, but Colombia’s health scenario is more complex as evidenced by widespread but opposing protests over President Petro’s proposed healthcare reforms. Last month, many Colombians celebrated Petro’s health reform, which includes initiatives like health worker training, community-based service delivery and an emphasis on prevention—all of which will improve primary care for marginalized communities. But, as Colombia’s population ages, its health burden is shifting away from the infectious diseases that primary care addresses and toward more complex and expensive treatments for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). The drastic shift to a public model focused on primary care does not reflect the current or future health needs of most of the country. Critically, the reform proposes to do away with the public/private model of health coverage that has been the cornerstone of Colombia’s health system for 30 years. Those who have been accessing care in the public/private model are deeply concerned because they fear that its complete eradication will lead to severe gaps in service delivery and coverage, particularly treatment for NCDs. So, just like those in support of the reforms, they also took to the streets. Colombia is a country at an epidemiological crossroads. It suffers from the double burden of disease—infectious and noncommunicable. Petro’s plan is perceived to be overly focused on primary health care, and by ending Colombia’s private/public model, many worry that the new health care system would not be up to the daunting task of meeting the health challenges that Colombians face both today and tomorrow.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

Events in the Ukraine have lifted the morale of anti-government protestors in Venezuela and elevated their expectations.

Conflicts over energy and natural resources are leading to social turmoil and posing serious challenges for investment projects all over Latin America.

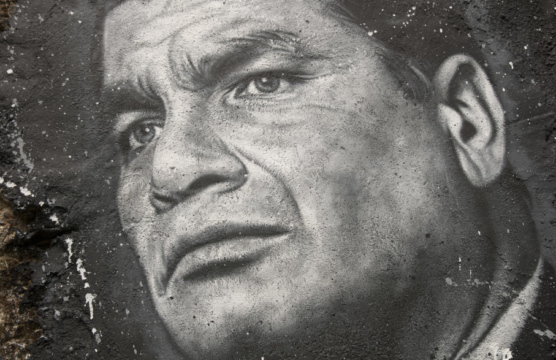

Ecuadordan President Rafael Correa battles an increasingly dissatisfied citizenry as he implements fiscal reforms to counter dropping oil prices.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro this month proposed controversial health care reforms. A doctor and patient at Clínica El Rosario in Medellín are pictured.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro this month proposed controversial health care reforms. A doctor and patient at Clínica El Rosario in Medellín are pictured.