The Politics Of Disaster Relief

After a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck Haiti, the aftershock reached China in ways that few anticipated.The earthquake forced Chinese leaders to navigate the tricky politics of disaster relief.

This article was originally published in Portuguese on May 8, 2020 by Valor Econômico under the title "Margaret Myers: Relação construtiva do Brasil com a China é decisiva."

In “What Could Brazil Want from China,” published in Valor (Sao Paulo) in February 2020, author Philip Yang expertly documents the many, striking successes of China’s model of development, from rapid urbanization and poverty alleviation to extensive educational achievement, contrasting these advances with Brazil’s own, relatively uninspiring, development experience.

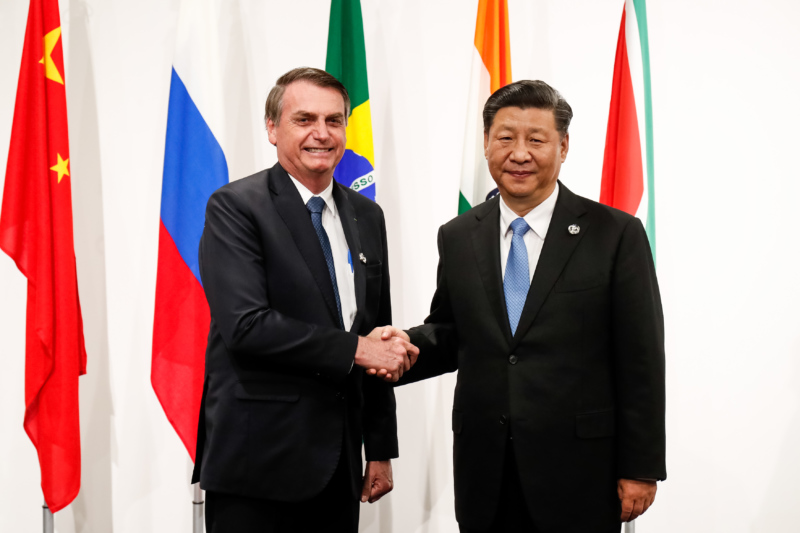

While noting China’s comparative developmental gains, Yang cautions against using China’s successes as justification for adopting authoritarian measures in Brazil, and notes a rejection by most in Brazil and many other democratic nations of undemocratic forms of governance. Yang instead calls for a strengthening of Brazil’s partnership with China, as the “greatest emerging power on the planet,” while noting the probable benefits of studying certain aspects of China’s development experiment.

There is indeed much to learn from China, extending far beyond the country’s remarkable economic transformation. Even in the US, where 66 percent of the population holds negative views of China, according to April 2020 Pew Research findings, many have noted the efficiency with which China has managed the coronavirus outbreak and its economic consequences. China will surely struggle to get its economy back on track in a sustainable way, but at least it has a clear plan—including, most notably, the “six ensures,” the “six stabilities,” and a color-based health code system reliant on big data. For many in the US, our plan of action is muddled at best.

It is worth noting, however, that when a country’s democratic fundamentals are fragile, enhanced engagement with China, even in pursuit of new economic opportunity or inspiration, as Yang encourages, has at times risked a decline in the quality of that country’s democracy. This can happen despite a population’s historical commitment to democratic principles and regardless of China’s intent.

For many in the world, the very example of China’s development experience has created something of a permissive environment for leaders with authoritarian leanings. China’s experience with centralized economic and political governance—much like Nicaragua’s pre-April 2018 and in other Latin American countries at different points in history—demonstrates that economic growth and even innovation can happen while maintaining a considerable degree of political control. In the case of China, though, the scale of achievement is greater, and Beijing’s foreign outreach has included the exportation of key elements of its governance model.

The so-called Beijing Consensus, characterized by centralized economic decision-making, corporate allegiance to state objectives, and long-term planning, among other qualities, has gained considerable ground among populations in Africa and Southeast Asia, although less so in the Latin American region, which despite some backsliding is still largely committed to its hard-won democratic gains. But in Thailand, for example, as Council on Foreign Relations’ Joshua Kurlantzick has noted, growing numbers of politicians, bureaucrats, and even journalists favorably contrast “China's undemocratic model of government decision-making with Thailand's messy, and sometimes-violent pseudo-democracy.” The same dynamic is playing out in many other countries across the globe.

Positive views of China’s self-termed “democratic dictatorship” are of course strengthened by the very public failings of the US and other democracies in recent years to sufficiently address the needs of their populations, whether in the context of Covid-19 or otherwise. These only feed growing global disillusionment with what are perceived by constituencies across the developed and developing worlds to be stagnant and unresponsive democratic processes. The Trump administration’s uncoordinated and uninformed response to the coronavirus has been an international embarrassment, exposing the country’s deep social chasms and economic vulnerabilities. US foreign policy has also defied logic over the past three years, standing in stark contrast, as Yang notes, to the perceived steady hand with which China operates.

Democracy is also vulnerable, as we’ve seen, to China’s particular approach to overseas engagement. Elsewhere in Latin America, the possibility of no-strings-attached Chinese financing and investment has led some governments to relieve themselves of the burdensome regulations and democratic oversight generally encouraged in the West and required by many international financial institutions. Decisions to erode existing standards are made by recipient governments, of course, and not by Beijing. But these decisions are often made with tacit support from China, which defers to the interests of host governments. And the trade-offs of rapid, non-transparent deal-making are numerous, ranging from heightened corruption and labor problems to steep environmental costs.

Additionally, democratic principles are potentially weakened by some of China’s cutting-edge technologies. The surveillance systems that China has sold to several countries in the region are in many cases politically innocuous, and deeply helpful to crime-ridden communities. But with added accessories, they have the capacity to increase social control and affect political outcomes. Governments will of course leverage technologies consistent with the values or political models that they decide to pursue. But with these technologies close at hand, Latin American leaders with authoritarian leanings can easily dismantle democratic fundamentals. The challenge for Brazil and other nations is to adopt new Chinese technologies while also accounting for these risks, and to ensure a policy environment that promotes a degree of technology transfer and data sovereignty.

At this point, Brazil’s democratic system faces many more challenges from within than from China, even as country’s governing institutions manage to uphold key democratic principles. The same can be said of many other democratic nations, including the US. And Yang’s prescription of enhanced Brazil-China engagement is a valid and important one. Brazil has much to gain from a more extensive and strategic approach to bilateral relations, including in the agricultural and energy sectors, as Yang notes. Much could also be gained by studying China’s innovative approaches to urbanization, automation, and in other areas.

But the sustained success of China’s model, despite its often-referenced drawbacks, will force a continued referendum on democracy. Even the strongest of democratic systems will be forced to confront their vulnerabilities and inefficiencies. Doing so effectively, as Yang recommends, will be critical for the well being of local populations and the system as a whole.

After a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck Haiti, the aftershock reached China in ways that few anticipated.The earthquake forced Chinese leaders to navigate the tricky politics of disaster relief.

What should we expect from a newly powerful Brazil? Does the country have the capacity and leadership to be a central actor in addressing critical global and regional problems?

By all accounts, Spain wants to bring change to the European Union’s Cuba policy. In so doing, it is tackling a foreign policy challenge that often sheds more heat than light.

Alan Santos / PR

Alan Santos / PR