The Washington Post & the OAS Secretary General

The OAS needs to be reformed, but the changes need to emerge from accurate analysis of the problems confronting both Latin America and the OAS.

The failure to narrow the inequality gap in Latin America, a need for effective economic integration, and the importance of investment in infrastructure and education were among the issues spotlighted during the XVII Annual CAF Conference sponsored by CAF - Development Bank of Latin America, the Inter-American Dialogue and the Organization of American States.

Immigration, drug trafficking, social unrest, election cycles, and innovation were also addressed during panel discussions at the September 4-5 gathering in Washington, D.C.

Each year, the CAF conference brings together government officials from Latin America and the United States, economists, lawmakers, bankers, business leaders, journalists, and academics to discuss the most pressing issues affecting the Americas. The 2013 conference saw record-setting attendance: More than 1,000 people took part in the two-day global conference.

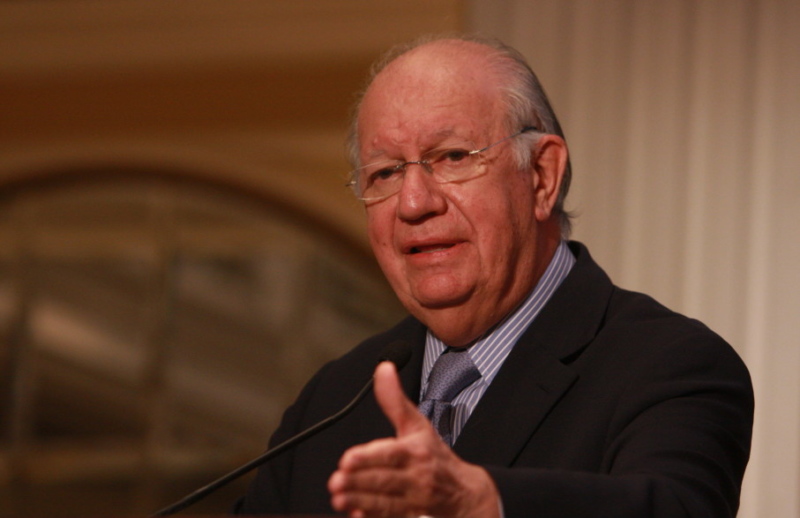

During a keynote address, former Chilean President Ricardo Lagos warned that the hemisphere, rather than pursuing needed integration, was gravitating toward an east-west division that separated countries on the Pacific Ocean from those on the Atlantic.

“I used to think of Latin America in terms of south and north, but I never thought of Latin America from east to west,” he said. He likened this emerging division to the one created centuries ago, when the Treaty of Tordesillas split the New World between Spain and Portugal.

“Now we have a similar situation, with the countries of the Pacific Ocean on one side and the Atlantic Ocean countries on the other. This is a huge mistake,” said Lagos. “We need to speak with a single voice, help those countries that are falling behind, and break the division between the Pacific nations and the Atlantic nations.”

He called on Latin America for greater involvement in rebuilding Haiti and in forwarding the peace process in Colombia. “If we resolve our own problems, we can engage in an inter-American dialogue with the United States on more equal terms,” he said.

Integration and alliances also came under discussion during a presentation by José María Aznar, the former prime minister of Spain and an advocate for the Atlantic Basin Initiative. The initiative was created in April 2012 to study political, economic, social, cultural and technological opportunities if countries look beyond traditional alliances of the North Atlantic.

“It is not true, as many say, that the future of the world is confined to the Pacific basin,” Aznar explained. Instead, he asserted “the Atlantic basin is the most important in the world” when measured by its institutions, values, skills, and resources, notably energy and water.

However, he said it is shortsighted to define the Atlantic community through the relationship between the United States and Europe. Rather, he called for looking at “the entire Atlantic, not only the north but also the south,” and he advocated for redefining Atlantic policy against a foundation of four geographic pillars: the United States, Latin American, Europe, and Africa.

Aznar joined former Uruguayan President Luis Alberto Lacalle of Uruguay and four other panelists in a discussion titled “Toward a New Transatlantic Society.” The panel was moderated by Daniel Hamilton, executive director of the Center for Trans-Atlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University.

Benita Ferrero-Waldner, the president of the European Union-Latin America and Caribbean Foundation, called for transatlantic relations to be based on the triangle formed by the United States and Canada, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. She said this configuration would hold up regardless of the ideological differences within the Western Hemisphere. But Jean-Louis Ekra, chairman and president of the Africa Export-Import Bank, lobbied for Africa’s inclusion, emphasizing that Africa is the fastest-growing region of the world after Asia and that it is an anchor in a south-south link with Latin America.

Pointing to trade negotiations between the United States and the European Union, Lacalle said regional bargaining is still ongoing “because we have not achieved an agreement for global free trade.” He said Europe sees trade from the viewpoint of a federation while the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) represents a more pragmatic approach to trade. He said protectionism and trade barriers have stymied integration.

He also expressed disappointment with Mercosur, which he helped to launch. “It has led to an association of governments that claim common characteristics—to the detriment of focusing on economics and trade, which was its original mandate,” he said.

Meanwhile, Harvard professor and former minister of planning for Venezuela, Ricardo Hausmann, described the Atlantic basin as “a huge opportunity for better integration between the US, Europe and Latin America.” Frances Burwell, vice president of the Atlantic Council, agreed, adding that the three regions share a growing interest in issues related to the economy and energy. She noted that Europe and the United States are involved in a “very ambitious” free trade project and suggested that South and Central American countries with US free trade agreements should explore joining the bloc.

Tenuous Advances

Panelists discussing the region’s economies warned that gains—including a dramatic decline in poverty since 2004—could be eroded as a result of tightening fiscal policy, a dearth of low-skilled jobs, and a reduction in public services. They said inequalities must be narrowed and infrastructure investment must be boosted if the region is to leverage its extended cycle of economic growth.

CAF President Enrique García, who moderated the panel titled “Latin America Looking Ahead: How to Achieve Economic Transformation,” told the conference that “modern growth is not only about reducing poverty, but improving equity.”

The panel included Inter-American Development Bank President Luis Alberto Moreno; Alicia Bárcena, the executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); World Bank Vice President Hasan Tuluy; Alejandro Werner, director for the Western Hemisphere at the International Monetary Fund; Colombia’s former minister of economy and now a Columbia University professor, José Antonio Ocampo; and Ernesto Talvi, director of the Brookings Institution’s Latin American Initiative.

The panelists acknowledged that improved fiscal management had opened the way for growth in the region and allowed much of Latin America to avoid the global economic crisis. But they said additional fiscal reforms and investment in infrastructure are needed for continued growth. García called for, at a minimum, a doubling of infrastructure investment over the next five or six years though public-private partnerships.

Werner said Latin America’s strong stretch of economic growth was nearing its end and the region needed to prepare for the coming economic slowdown in China, whose hunger for commodities has helped drive Latin America’s economic expansion. Moreno, meanwhile, pointed out that the region’s economic boom did not come in tandem with increased productivity. In fact, he said Latin America lost more than 5 percent of productivity over the decade. He cited South Korea’s high productivity, saying that the Asian nation “invests more in innovation than all of the Latin American countries together.”

CAF’s García said Latin America must meet the challenge of adding value to its “natural advantages” by investing in technology and education.” Talvi said educational attainment was critical for transforming the region, and Bárcena said investment in education needed to include structural reforms. She also called for increased tax revenues, social policies to continue the fight against poverty and inequality, and infrastructure investment that includes universal broadband Internet access.

World Bank Vice President Tuluy reminded conference participants that the region’s economic good times were not universal: South America experienced tremendous growth but Central America and the Caribbean did not. At the same time, Ocampo challenged the idea that Latin America had completed a “decade” of expansion, saying 2003-2007 were good years but “since then growth in Latin America has been less than 3 percent, and this is very poor.”

New Platform for Addressing Drug Problem

In an animated panel discussion on drug trafficking in the region, Organization of American States’ Secretary General José Miguel Insulza detailed his organization’s recent Report on the Drug Problem in the Americas. He said the study, prepared at the request of leaders in the region, “does not arise in the midst of a divisive debate but as part of the important consensus that this is a very serious problem in a continent that consumes half of the world’s heroin and cocaine and a significant amount of the other remaining drugs.” Óscar Naranjo, former director of the National Police of Colombia, said the report provided a platform for “reformulating drug policy, humanizing it, and giving it the status of a public health issue.”

The director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, Gil Kerlikowske, said several ideas presented in the OAS report coincide with international treaties and with US government efforts. “We are very much all in this together,” he explained. “There is no such a thing as a production country, transit country, or consumer country. We all face serious difficulties when dealing with this.”

Other members of the panel moderated by Colombia’s former minister of foreign affairs, María Emma Mejia, said that the drug problem manifests itself in different ways in different countries and there is no single fix-all solution for the hemisphere.

Guatemalan Minister of Foreign Affairs Fernando Carrera described it as a multidimensional challenge that involves security, social, and public health issues. “Breaking the paradigm that law enforcement should be the only answer to address the drug problem was one of the main conclusions of the report,” he noted.

Nelson Jobim, Brazil’s former defense minister, said a “macro” understanding of the problem is in place but there is a need to tackle the more complex “micro view.” He said that includes determining which domestic departments and agencies have authority over which elements of the process, from treatment to punishment. He said the answers will depend on a multitude of factors, including the type of drugs and domestic policies. Jobim said it will not be easy to merge by-country approaches into a global solution for a global problem.

Jorge Castañeda, Mexico’s former secretary of foreign affairs, talked about the deep economic impact of drug trafficking in Mexico. Beyond the widespread social implications, including violence, he said that there has been a stunning negative impact on things such as foreign direct investment.

Political Trends

In opening the conference, OAS Secretary General Insulza said the region faces a “test for democracies” with several presidential elections in the final months of 2013 and in 2014. Insulza said that although the elections will take place against a backdrop of economic growth in most of the countries, they are also occurring in the region with the world’s greatest levels of inequality.

Details of the political cycle were examined during a session moderated by Inter-American Dialogue President Michael Shifter. Panelists discussed upcoming elections that include presidential bids in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Panama, and Uruguay, as well as municipal and legislative in Haiti and Venezuela.

Manuel Alcántara, a professor at the University of Salamanca in Spain, presented an overview in which he spotlighted weaknesses in the electoral process, including low political participation, little serious competition in electoral races, and even incidents of vote-buying. He also said political parties are weakening.

Alcántara said these trends are not limited to Latin America but are becoming more widespread—and troubling—globally.

He said one of the most important elections next year will take place in El Salvador, where he said the candidate from the right and the candidate from the left will be closely matched.

Juan Gabriel Valdés, former foreign minister of Chile, told the conference that Michele Bachelet has an overwhelming lead in her bid for a second presidency and she could even win the September 17th elections outright without the need for a second round of voting.

“For those outside, Chile is seen as a place where people are leaving poverty … a society that looks good to the outside. Democratic institutions are working,” Valdes said. He added, however, that street protests are a sign of an underlying uneasiness, a fear that lawmakers cannot get issues advanced.

“There is a sense that Chilean society is changing,” he said. “The society feels that it has lost its sense of community.” He called for a new constitution, parliamentary reform, and a revamping of the system of higher education.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has not made clear if he will run for a second term in next year’s May elections. Rodrigo Pardo, director of RCN Television and a former foreign minister of Colombia, said electoral reform has given the incumbent a tremendous advantage, but a re-election victory may hinge whether the Santos government can secure peace with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Pardo called Santos “the obvious candidate for the election.” However, he said there have been dramatic ups and downs in electoral surveys and Santos seems disconnected from the people.

Pardo also discounted those who say that FARC negotiations in Cuba were launched as a strategy to help Santos win the election. He said the negotiations have put the Santos government in an untenable position. “The polls say the majority of Colombians want a peace accord with FARC, but the surveys also show that the majority of them do not want the government to give up much to achieve that,” he explained.

In Venezuela, meanwhile, the election landscape reveals that Hugo Chávez’s cult of personality remains strong even after his death, making it difficult for incumbent Nicolás Maduro as the country gears up for municipal elections in December.

“There’s an expression in Venezuela that ‘Maduro isn’t Chávez,’” said pollster Luis Vicente Leon, director of research firm Datanálisis in Caracas. “Maduro’s campaign takes the position he is doing the work of Chávez, but Maduro doesn’t have the popularity and internal control of the chavistas that he needs.”

Leon said there may be a push to vote “strategically” to punish Maduro. However, he said that the movement started by Chávez is capable of winning, depending on how much money the populist government “takes into the streets.” Going forward, Leon said outcomes of future elections will prove harder to predict.

Chávez commanded international attention and no one else in the region has emerged to fill the role he held, according to Carlos Basombrío, Peru’s former vice minister of the interior. Basombrío said Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa does not have Chávez’s ambitions, and he leads a smaller country.

Basombrío said there is also a growing idea that Latin America has reached a maturity level where it could have a partnership relation with the United States. However, he agreed with Alcántara that there are many weaknesses in the region’s democratic institutions, including corruption.

Discussing Paraguay’s political landscape, journalist Luis Bareiro from the newspaper Última Hora, said the public’s distaste for corruption is so deep in Paraguay that traditional political parties can only win elections if they choose outlier candidates with no political experience. “The parties have become electoral machines that have to find non-political figures to post as candidates,” he said. “If they do that, they can win. But they can’t win with their own candidates from inside the party.”

Bareiro said the result is ineffective government. He noted that this phenomenon springs, in part, from anti-poverty efforts that have enfranchised more people. Not so many years ago, Bareiro said, the longstanding power of the private sector, led by ranchers and farmers, would have wielded greater influence.

What is Sparking Social Protests?

Democratic governments in Latin America are now also facing an emerging wave of social protests. A panel moderated by Moisés Naím, senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and former trade and industry minister for Venezuela, examined: “What is Behind the Emerging Global Social Protests? What is Next?”

Nancy Birdsall, president of the Center for Global Development; Eurasia Group senior analyst João Augusto de Castro Neves; Wu Guoping, assistant director of the Academy of Social Sciences of China; TUSAID senior fellow Kemal Kirisci, who also directs the Turkey Project at the Brookings Institution; Guillermo Fernández de Soto, director for Europe at CAF - Development Bank of Latin America and former minister of foreign affairs of Colombia; and journalist Ramón Pérez-Maura, from Diario ABC in Spain, talked about recent protests in Chile, Brazil, Mexico, China, and Turkey. They concluded that their origins were not necessarily the same; some were driven by economic concerns and others were protests in favor of political rights.

Naím also said that not all of the protests should be seen as problems. “In some cases, protests are very healthy … and they can be the beginning of a solution.”

Birdsall said many of the protests have been attributed to the rising middle classes, but she cautioned affixing the middle class label to an overly broad spectrum of the population. “If you think about people who are achievers in the material sense, then you’re talking about a middle class that’s not going to back into poverty because the prices of food go up 20 cents,” she said, referring to media reports that people protested in reaction to the economy.

“There is another group of people in places like Brazil,” Birdsall continued. “They have escaped poverty but are not [safely entrenched] in the middle class. These are people who are not below the poverty line but who are still far from the middle class. I call them the ‘strugglers.’”

Castro Neves said rising bus fares might have triggered Brazil’s street protests “but it could have been anything. Bus fares were not really the issue.”

Just as Latin America’s protests cannot be attributed to a single homogenous source, China’s protests need to be examined at a more refined level, according to Wu Guoping, assistant director of the Academy of Social Sciences of China. “In China, when we talk about protests, we have to divide the discussion between [protests] of the poor and those of the middle class.”

He said that in Brazil, the middle class is marginalized because government supports are all directed to the poor. By contrast, reform in China benefits the middle class. “We’re giving the middle class food security and better public services—better education, better medical care,” he said.

He added that there is also a division between how well the government serves urban and rural residents.

For China, if you arrive in the campo from the city, you have trouble integrating. At the same time, if you go to the city from the campo, you can’t pick the best schools because you’re poor and don’t have any money,” he explained. Guoping added that there is also a separation between those in the east of the country and those in the west.

When it comes to Turkey, Kirisci also agreed that the middle class is not homogeneous. “There is a part of the middle class that is very much connected to globalization,” he said, adding that this population felt that something had been taken away from it when the government began taking steps to qualify for EU membership. He described the protests in Turkey as citizens embracing democracy in the face of a “prime minister that wanted to shove down the country’s throat all these majestic projects.”

Fernández de Soto said Colombia’s protests tend to unfold in rural areas and have agrarian themes. Pérez-Maura and other panelists noted that the protests are most likely fueled by people who fear, with justification, what will happen to them when the economic boom ends and they are left jobless.

The panelists also discussed the range of ways governments responded to the protests—rather mildly in Turkey and Brazil and more dramatically in Colombia, where the defense minister accused FARC “terrorists” of infiltrating otherwise peaceful protests.

Regional Impact of Immigration Reform

Beyond elections, the hemisphere’s near-term political agenda may also be marked by long-awaited immigration reform in the United States. A reform measure in the US Congress is being watched by countries in Latin America and the Caribbean because of its direct impact on them. The vast majority of undocumented workers in the United States are from Latin America, and the economies of several countries depend on the remittances that those workers send home.

Andrea Bernal, director of news programs for NTN24, moderated a panel that considered lasting immigration reform. American University professor Robert Pastor said the United States has undergone profound social and cultural shifts over the past 40 years and the gap between Anglo Americans and Latin Americans has narrowed, with Hispanic Americans becoming a defining part of the population.

“There are more Mexicans living in the United States than Canadians living in Canada,” Pastor said to illustrate the scale of the shift. “We are now socially and culturally integrated and that makes immigration reform possible.”

Through NAFTA, the United States allowed cross-border production and the free-flow of capital and goods but not people, noted Adrián Bonilla, the secretary general of the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO). Since then, a number of security issues, including terrorism and drug trafficking, have become intertwined in immigration policy, allowing lawmakers to justify a non-pragmatic approach in recent years.

The panelists noted that US immigration is a phenomenon that is changing societies on both sides of the Rio Grande. It has brought out the political clout of Hispanic Americans and its focus on securing the US-Mexico border has carried a hefty price tag for the United States. Lázaro Cárdenas, the former governor of Michoacán, Mexico, noted that while net immigration is about zero now, there are now more US-born people in Mexico than ever before.

Alberto Cardenas, chairman of the American Conservative Union, said while immigration reform will not be easy, it will be critical for a healthy economic landscape and thriving business partnerships between the United States and Latin America. He added that the retirements of the aging Baby Boomer generation will fuel the need for new workers from the immigrant ranks.

At the same time, Cardenas noted that no country in Latin America has immigration laws as “soft” as those of the United States.

Doris Meissner, senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, acknowledged the interconnections between the United States and Latin America when it comes to immigration and said a “dysfunctional immigration policy” is the biggest obstacle to regional integration. She categorized US immigration reform as a domestic issue but said its benefits will be far reaching.

“The United needs immigration in order to thrive into the future,” Meissner said. “If we develop immigration flows that speak to our market needs, that will stimulate the economies of the countries sending the immigrants.”

Former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson said immigration reform “reduces the deficit, it creates jobs, it has more people contributing to the Social Security system, it’s good for technology.” However, he cautioned that reform will not solve every problem overnight. The path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants will be 13 years under the proposed legislation, and applicants will need to meet certain criteria, including English proficiency.

Richardson added that while the United States must implement reform, Latin American countries with significant migration have their own homework. He said they need to change social conditions so that their citizens do not have to leave.

Generating Innovation

A session titled “Young Leaders: Pursing innovation and Entrepreneurship in Latin America” brought agreement from its participants: Latin America needs greater innovation and smoother pathways for entrepreneurs but there are myriad obstacles.

Michael Penfold, director of public policy and competitiveness for CAF - Development Bank of Latin America, said scale is a problem, noting that a 28-year-old company in Latin America is typically only a third of the size of a 28-year-old company in the United States. He also pointed out that productivity is low, there is too much informality in Latin America’s labor force, and the best talent is not employed or is employed in companies that are not developing technology talent. Generally, he noted, Latin American companies are not adequately investing in technical and creative people.

He pointed to poor intellectual property protections in the region as another disincentive to innovation, and noted that even countries seeking to build technology clusters do not understand that they must also import talent. He said the region also lacks financial channels for commercializing innovation.

Penfold said Latin America has the talent to compete with the United States and innovation is on the policy agenda of countries in the region, but it is difficult to jump forward given the other barriers. Meanwhile, panel moderator Patricia Janiot, senior anchor for CNN en Español, blasted the region’s universities for failing to serve as pulse points for entrepreneurial activities.

As part of the discussion, Alejo Ramírez, secretary general of the Ibero-American Youth Organization, detailed results of the first survey of Latin American youth. The survey revealed that Latin America’s young people feel strong solidarity with other youth in the region and they are—surprisingly, given the high joblessness and rates of violence affecting them—generally optimistic about the future.

The survey also revealed that college is an aspiration of Latin America’s youth but it is too-often not achieved. This gap is troubling in Latin America since educational attainment is a bellwether for future success. Ramírez, noting that Latin American youth end up with neither education nor employment, called for greater investment in youth.

Uruguay’s decision to legalize marijuana and control its production and distribution was also mentioned as an example of innovation and risk-taking. Diego Cánepa, secretary of the presidency of Uruguay, participated on the panel and explained that innovation is necessary for a strong society and a responsive government.

He said Latin America needs to understand that innovation is linked to failure. “We have a hard time accepting that failure is part of the journey,” he said. “And that is why we lose the capacity for innovation.”

The panel included three successful entrepreneurs who described their initiatives:

US Secretary of State John Kerry was scheduled to address the CAF conference but was forced to cancel in order to testify in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on President Barack Obama’s proposal for military action in Syria.

The OAS needs to be reformed, but the changes need to emerge from accurate analysis of the problems confronting both Latin America and the OAS.

History tells us that economic crises cause large increases in poverty. The most recent economic crisis will cause Latin America’s GDP to contract around 2 percent in 2009.

Since achieving independence in 1804 to become the world’s first free black state, Haiti has been beset by turbulent, often violent, politics and a gradual but seemingly unstoppable slide from austerity to poverty to misery.