Fidel at 90

Cristobal Herrera/Associated Press / Flickr / (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Cristobal Herrera/Associated Press / Flickr / (CC BY-NC 2.0)

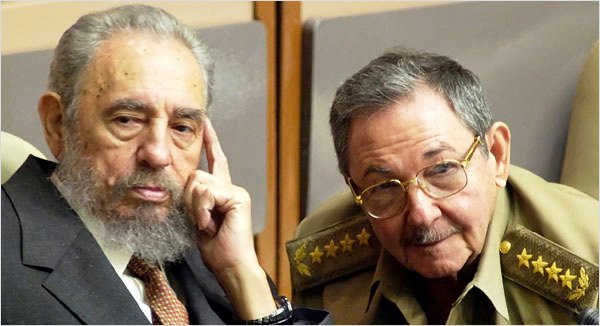

Fidel Castro turns 90 this week. His revolution, one of the world’s most enduring, is 57 years old. A decade has now passed since he turned power over to his younger brother Raul. Few revolutionary leaders have managed to govern so long. Even fewer, if any, have survived so long after giving up their authority. By any account, he was Latin America’s most prominent 20th century leader. What is unclear is how he will be remembered—for governing Cuba with a progressive agenda or for keeping the island isolated and underdeveloped.

Some Cubans are convinced that Fidel continues to hold supreme power on the island. Most observers, however, are certain Raul is now in charge and the only question is how much influence Fidel still exerts over the affairs of state. It is hard question to answer. Except for the highest echelons of government, the Cuban political process is opaque. What goes on in top government circles is unknown outside those circles. The rest of us are forced to speculate.

He almost surely exercise some political sway. The slow progress of Cuba’s economic reform program, a high priority for Raul Castro, leaves the impression that a political heavyweight is leaning in the opposite direction. Since the program was officially approved five years ago at one of the Communist Party’s infrequent conclaves, only 20 percent of its mandates have been implemented, according to Raul himself. Fidel, however, does not always get his way. Almost any interpretation of his intermittent published writings suggests that Fidel is not happy with how his successor is managing relations with the US. Fidel, for instance, was very publicly critical of how the Obama family’s trip to Havana was handled, but his influence on this matter seems modest at best.

Another area of conjecture is whether the socialist state that Fidel and Raul have run for half a century can be sustained—or whether Cuba will quickly be pulled into the gravitational orbit of the US and move toward some form of representative democracy and market economics. It may turn out to be an awkward mix, but the likelihood is that gravitation will prevail. With Venezuela nearing collapse, Cuba’s economy has already become increasingly dependent on US visitors and remittances.

The US has long been a reference point for Cuba. From the outset of his revolutionary government, Fidel defined Cuba as an adversary of the US, with an antithetical set of values. For the new Cuban authorities, patriotism meant removing all vestiges of US influence from the island, and stopping any further trespassing on the island’s sovereignty by the giant to the North. Today, in contrast, most ordinary Cubans are enthusiastic about renewing normal relations with the US—as amply illustrated by their animated welcome of Barack Obama, and the great excitement surrounding his visit. By no means do Cubans align themselves with US policies nor are they ready to wholly adopt American values, but they want to bury the hostilities. They view reconciliation as the gateway to the modern world, to technology and information, to new opportunities—and perhaps an end to the daily battle to feed themselves. They are no longer interested in protecting stale ideas about how the world should work. Instead, they want to participate in the world.

Fidel Castro has been a polarizing, controversial figure in Latin American history, but he will surely be one of its most important chapters. For many in the region, he remains a heroic figure for his struggle against US domination in his own country and in hemispheric affairs generally. Cuba was the only Latin America nation kept itself independent of the US during the Cold War. Like no other Latin American leader, Fidel will be remembered for bringing attention to the region’s vast social injustices and its profound inequalities in wealth and opportunity. But many others consider him as a cruel autocrat, who insisted on controlling all aspects of life in Cuba—who sacrificed his citizens to an outmoded, unworkable ideology and to his own ambitions. He was a man who initiated a bold experiment. But his ideas never evolved. He left his country poor and backwards. The world has left him and Cuba behind.

For the original Portuguese article, click here.

For a Spanish translation, click here.