Measuring Up?

PREAL publication analyzes how Latin American and Caribbean countries performed on PISA tests.

This post is also available in: Spanish

Technical education at the secondary level entered a state of crisis in Latin America in the 1980s. Based on a conception of professional training, the crisis of the import substitution model made it increasingly irrelevant. As a result, its size and appeal as an alternative to academically oriented secondary education has decreased in many countries in the region.

Technical education’s identity crisis is problematic. In most countries in the region and for most young people, secondary school is still (and will continue to be) the terminal step in their academic preparation. In turn, it is imperative that secondary education provides students with the tools needed to enter the labor market. This requires cognitive skills, not only in the traditional academic way but also in a deeper analytical way. This, however, would not be enough. Ideally, it should provide them with socioemotional skills that are typically acquired through practical experiences, as well as modern technical skills.

Beyond the necessary process of skills acquisition taking place in the context of a separate technical education system or as part of the general secondary system, it is imperative to advance in the implementation of a competency-based model that features stronger links to the professional world and the economy’s productive sectors.

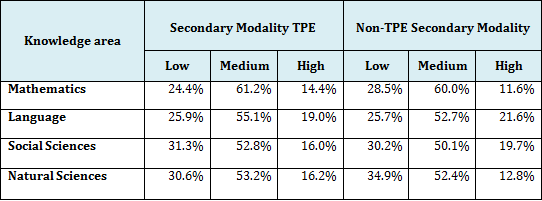

Argentina is not foreign to these challenges. Today, there are approximately 1,600 secondary technical schools in the country serving over 600,000 students, the equivalent to 15.6% of total secondary enrollment in the country, according to a 2014 report by the Ministry of Education. While this may be just one quality indicator, students in technical education obtained slightly better results in mathematics and science in the Operativo Nacional de Educación (2013) compared to students from non-technical schools, and obtained similar results in reading. Data from the OECD suggests that while students in the highest socioeconomic quintile in technical schools fare worse in mathematics in the PISA test than those who attend academically oriented secondary school, among students from the lowest socioeconomic levels, students from technical secondary schools fare better than their counterparts.

Source: Operativo Nacional de Educación (ONE) 2013. DNECE.

Ministry of Education. INET – Planning Unit

In 2005, the Argentinian Congress approved Law 26.058 for Technical and Professional Education, which regulated technical education not only at the secondary level but also at the tertiary level, as well as professional training programs. An analysis of this law suggests that it includes several potentially powerful elements for the regulation and management of a technical education framework at the secondary level. However, as is usually the case with this type of issues, ‘del dicho al hecho hay un largo trecho’ – the reality in the sector seems to be quite distant from the framework contemplated by the law. The possibility of bridging the gap between the law and reality to create a more modern technical education model might increase as Argentina began a new phase in December 2015.

One tool established by this law is the professional profiles. The National Institute of Technological Education (INET, in Spanish) must, in a consultative manner, establish these profiles for different socio-productive sectors and, based on them, jurisdictions must formulate the corresponding curricula. As long as these profiles are defined based on an exhaustive analysis of the competencies demanded by employers, this aspect of the law grants INET (and through INET the system as a whole) the ability to give greater practical relevance to the academic training provided in schools. These profiles also constitute the basis for the national catalogue of degrees and certifications, which should be their exclusive and selective payroll in the national territory.

There are currently 22 frames of reference at the secondary level, 10 for higher education, and 95 for professional training, approved between 2006 and 2015. These correspond to professional profiles defined in sectorial meetings organized by the National Council for Education, Labor, and Production (CONETyP) during the 2005-2015 period. Beyond the fact that some of them may require updates and that new profiles may be needed, this list constitutes a useful starting point.

A second tool is the federal registry for technical and professional education institutions. The law dictates that only those institutions enrolled in the registry will be able to award degrees and certifications. The Ministry, along with the Federal Council, must set the quality parameters and criteria to which the institutions in the registry must adhere. While the law does not establish the process through which institutions are evaluated for the fulfillment of these criteria, it does acknowledge the need for such a process and in consequence establishes what can be considered a control system for the quality of educational supply.

To this date, the registry features 3,227 professional and technical education institutions and 1,147 institutions of different levels and categories for a total of 4,374 institutions. Official resolutions establish the criteria for entry to the registry. However, there are no parameters for quality evaluation. In fact, institutions are incorporated through admission forms completed by the institution itself and communicated through jurisdictions. It is up to each jurisdiction to approve the admission request. This generates strong suspicions about whether the registry fulfills the role of quality control system as previously suggested.

The third tool contemplated by the law is evaluation. Jurisdictions are responsible for evaluating (and certifying) that students have demonstrated the required competencies. At the same time, INET has the responsibility of designing the tools needed to evaluate the quality of education programs and must participate in the evaluation. The law does not set limits on the types of evaluation, which leaves open the possibility of including elements from learning measurements and/or skills acquisitions by students. Moreover, the law calls for coordination with the National Institute for Statistics and Census (INDEC) to determine students’ labor market integration rates.

INET developed the so-called Institutional Self-Evaluation (AEI, in Spanish), which has been applied in 14 provinces so far. It covers contextual variables, educational trajectory, institutional performance, and pedagogical practices, but not the fulfillment of competencies. With regards to the evaluation of graduates’ reintegration into the job market, INET conducted a national survey in 2013 and released a report on findings. However, there is still no system in place for permanent tracking through INDEC.

Finally, the law also established a National Fund for Technical and Professional Education, with resources from Treasury to be invested by jurisdictions. While the law establishes eligible ways to use these resources, the list is broad and incorporates the ‘institutional projects’ category, which grants, in principle, significant flexibility for allocating these resources. In the same way, jurisdictions’ distribution criteria are not set by the law but are instead determined by the Federal Council. These two characteristics, as long as national authorities reach a consensus with the provinces, allow the Fund to act as a financial mechanism that strengthens the other aforementioned tools, directing resources towards usage that contributes to improvements in the quality and the relevance of technical education.

The Fund’s resources[2] ($3,336 million pesos, or over $200 million dollars, in 2016) are significant not only in absolute terms but also in relative terms, since – given the fact that provincial resources are used fundamentally for payroll purposes – they represent a very important source of flexible funding. However, in practice these resources do not seem to be invested in a strategic manner to improve the quality and relevance of technical education. Firstly, the lack of concrete projects has led to a significantly subpar execution in the use of resources, as evidenced by the fact that provincial accounts are equivalent to nearly 50% of the Fund’s annual allocated funds. Secondly, the criteria to approve improvement plans for financing with Fund resources do not include references to any indicators of quality or relevance of the education provided; instead, the criteria are focused on input indicators. Therefore, it is doubtful that the allocation will be optimal with such an approach.

Together, these four tools have the potential to serve as a regulatory and incentives framework to guarantee the quality and relevance of technical education. (1) The confluence of developed profiles in coordination with the business sector, (2) a registry that acts as a true quality accreditation system, (3) an evaluation system that generates data on learning results and employability, and (4) the allocation of resources towards the desired achievements, constitute a management model geared towards improving the quality and relevance of the system. All of this is completely compatible with the current law. Its effective implementation requires operational agreements between INET and jurisdictional authorities. It is in everyone’s interest that this is achieved.

[1] I want to thank INET personnel for sharing with me information that was extremely useful in elaborating this piece. The analysis is the author’s responsibility.

[2] The resources are not for the exclusive use in secondary technical education and can also be utilized in the two other sub-sectors considered by the law.

Photo credit: Rodolfo R. / Flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0

PREAL publication analyzes how Latin American and Caribbean countries performed on PISA tests.

The Fernández administration’s refusal to comply with a US court order to pay holdout hedge funds has once again landed Argentina in default.

Event participants discuss Education Ministry and highlight difficulty of balancing political pressures with long-term goals.