How to improve the quality of education in Latin America

The author suggests the key to improving the quality of students in Latin America rests on reading comprehension.

This post is also available in: Spanish

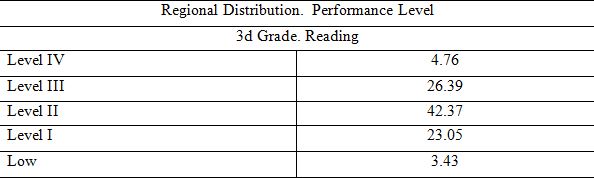

The results from TERCE highlight one of the biggest issues in the education sector in Latin America. The elephant in the room, if you may, is that most children do not learn how to read at the proper age. According to TERCE, 2 out of 3 third grader students do not reach higher than Level II in the reading test.

Low reading achievement means, in the short term, low basic skills upon graduation, and low income and low quality of life in the long run. Year after year these findings are corroborated by national assessments systems and by other international ones. However, little, if anything, seems to be done to correct this serious recurrent problem.

In addition to socioeconomic conditions, there are many reasons why reading ability is low in early grades, including: developmental delays (often due to limited investment in early childhood education), minimal instruction time (short academic years and school days aggravated by the days lost to strikes), limited practice (curriculum is too ambitious), inadequate pedagogy (teachers are not trained correctly to teach reading), lack of effective instructional materials (many textbooks used to teach reading are inadequate), and teaching in non-native languages (lack of support for the introduction of literacy in mother tongue). It is thus common to see students in third and even sixth grade that cannot process an acceptable volume of text and thus cannot understand the text used in follow-up instruction.

If students’ performance were assessed earlier and assessment results used to identify problems and ways to correct them, students would have a chance to improve their reading skills. In this way, their learning outcomes at the end of primary and secondary school would be better and, eventually, labor market outcomes would be better too.

I want to propose one factor that I believe is critical: many teachers do not know how to teach reading effectively. The argument is simple: Early-grade reading strongly affects the efficiency of an education system. Much of the grade repetition and dropout we observe could be avoided if students were able to read at the required speed early on. Literally billions of US dollars could be saved every year if correct teaching methods were put in place. Early grade reading skills also increase the probability that students will stay in the system and learn. Over the long term, this has significant implications for individual productivity in the labor market. This is an issue that affects most students but particularly those from lower-middle and low-income families.

Some people say that improving the quality of education systems requires a systemic approach rather than any single education reform. However, if I were in charge of an education system and seeking to improve quality, my top priority would be to improve the way students are taught to read.

How can students be taught to read more effectively and earlier? I propose what is being developed and tested in some countries worldwide by some donors, governments, and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). As Helen Abadzi explains[1], the idea is to improve comprehension by:

An EGRA (Early Grade Reading Assessment)[2] instrument was developed to implement this approach. It includes activities to develop literacy skills (emergent literacy, decoding, and confirmation and fluency), and tasks covering phonemic awareness, phoneme segmentation, oral vocabulary, listening comprehension, letter identification (names and sounds), syllable naming, non-word reading, familiar word reading, and oral reading fluency with comprehension.

This approach is already supported by preliminary yet solid evidence about its benefits. For example, in several countries around the world, including, for example, Yemen, Cambodia and Peru, the number of illiterate students was reduced significantly over the course of just a couple of years, in some cases by half, as in Cambodia where the percentage of students who could not read was 42% in 2010 and by 2012 had dropped to 22%, or in just in months, as in rural Peru where students in the Polaris schools improved their reading comprehension by almost 50% in less than six months.

Latin American authorities should start paying more attention to this issue and learn from these successful experiences. It is really troublesome to see that, year after year, a significant number of children are literally wasting their time by going to school and not learning how to read. The cost to the system of high repetition and dropout rates amounts to billions of US dollars. Isn’t it time to start identifying who is accountable?

[1] Abadzi, H. 2008. Efficient Learning for the Poor: New insight into literacy adquisition for children. International Review of Education. Vol. 54, No 5-6. Abadzi, H. 2013. Literacy for All in 100 Days? A research-based strategy for fast progress in low-income countries.

[2] Early Reading: Igniting Education for all. A report by the Early Grade Learning Community of Practice. Research Triangle Institute, 2011

The author suggests the key to improving the quality of students in Latin America rests on reading comprehension.

In comparing the two regions, the author finds “time on task” is an important factor to consider.

Why Pakistan represents “the biggest education reform challenge” and 12 lessons that are applicable to reform efforts around the globe.